Poor people are different to rich people, and not only in the amount of money they’ve got. They are also different in something that flows from it.

It’s (lack of) ease. And the consequences can be severe.

Economist Sendhil Mullainathan and psychologist Eldar Shafir outline these in their book Scarcity: Why Having So Little Means So Much.

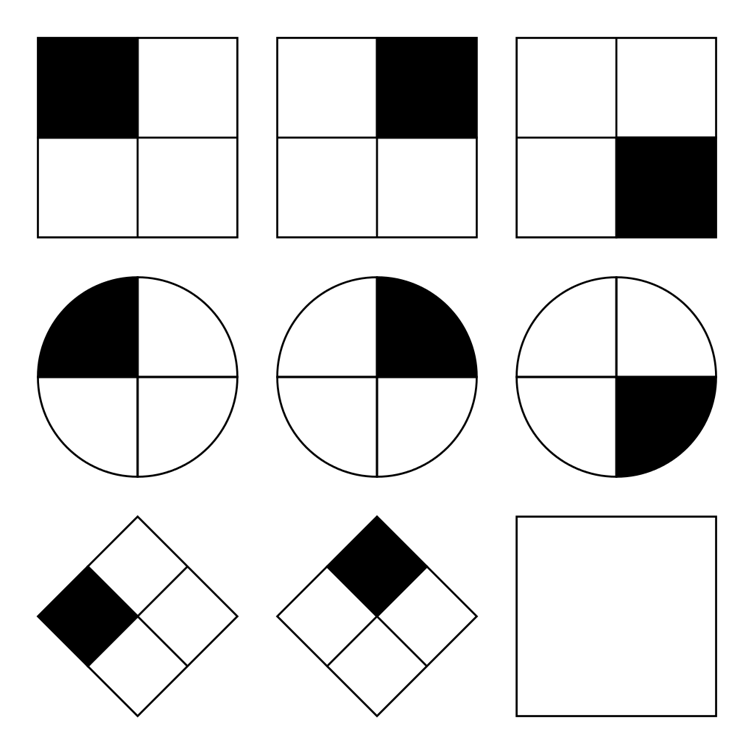

They asked shoppers at a New Jersey mall to take part in a so-called fluid intelligence test. Fluid intelligence is problem-solving ability unrelated to language or knowledge.

The test is usually presented as a series of eight images, each different from the one before, followed by an invitation to guess the ninth.

What’s in the missing box?

It’s usually pretty easy. And it was indeed easy for the first half of the shoppers they tested. Comparing the scores against self-reported income, the researchers found no significant differences – “the rich and poor looked equally smart”.

Just before they presented the first half of shoppers with the test, they also presented a hypothetical scenario:

Imagine that your car has some trouble, which requires a $300 service. Your auto insurance will cover half the cost. You need to decide whether to go ahead and get the car fixed, or take a chance and hope that it lasts for a while longer. How would you go about making such a decision?

For the second half of shoppers they presented the same scenario with just one change. Instead of the car service costing $300, it cost $3,000.

The one simple change had a remarkable effect on the test results of just one group of shoppers – those on low incomes. Although completely fictional, the scenario got them thinking about how they couldn’t afford a $3,000 bill from out of the blue. They mightn’t know where to find the money.

Instead of performing as well as the high earners (which low earners had done without the $3,000 prompt) they did dramatically worse. Their mental impairment was as bad as if they had lost an entire night’s sleep.

Stress is costly when ends can’t meet

The researchers have replicated the results time and time again. Even when they pay for correct answers (which might be expected to incentivise low earners more than high earners) low earners can’t concentrate enough to do well.

The authors’ conclusion is that it is incumbent on authorities not to send such people over the edge – not to make them fill in multi-page forms or reapply for assistance or attend recurring pointless meetings, and not to send them unexplained unpayable bills out of the blue – not to do anything that will remind them of how their finances don’t really allow them to cope.

Read more: The bad bits of ParentsNext just came back

When that happens, when what Mullainathan and Shafir call mental bandwidth is flooded, it is hard to think properly about things such as caring for children and getting work.

Australia’s treasury gets it. Its well-being framework sets out five points it believes should be considered in designing programs and policies. Point five is the cost to individuals of “dealing with unwanted complexity”.

Not so treasury’s political masters. When on Thursday the government boosts JobSeeker by a meagre $25 a week, it will cut the amount job seekers actually receive by a net $50 per week because of the end of the coronavirus supplement.

Mutual obligations impose stress

To offset that generosity – the first real increase in the base rate in 30 years – from April 1 it will ramp up its “mutual obligation” requirements. Job seekers will have to show they have applied for 15 jobs a month, climbing to 20 jobs a month on July 1 – that’s a fresh application every working day.

Failures will attract demerit points. Too many demerits and payments will be stopped.

There will be increased auditing of job applications to ensure they are “genuine”, a return to the compulsory face-to-face meetings suspended during the pandemic, and a dob-in line for employers to report job seekers they think aren’t genuine.

That this will dangerously ramp up stress on the people most susceptible to it, and make it hard for them to do things such as care for their children, ought not to surprise the government.

It has been considering the three-volume report of its Productivity Commission inquiry into mental health for nine months.

The report says stringent mutual obligation requirements might do more than stress those who take part — they might precipitate “clinically defined mental illness in previously well participants”.

For people with preexisting problems, “sound reasons and plausible evidence suggest this could aggravate their illness”.

The government ought to have learnt from repeated mistakes.

A Senate inquiry found the compliance measures associated with its ParentsNext program caused “anxiety, distress and harm”. Post-pandemic, it reinstated those compliance measures.

Robodebt should have been a wakeup call

Its unsolicited “robodebt” demands for repayments of thousands of dollars per recipient the Federal Court found was not owed caused what another Senate inquiry found to be “breakdown, anxiety, depression requiring medication, sleeplessness, stress causing physical illness, and fear”.

The ministers who announced the program in 2016 were Scott Morrison (then treasurer) and Christian Porter (then social services minister).

Read more: Robodebt was a fiasco with a cost we have yet to fully appreciate

They promised that smarter use of technology would “better manage our social welfare system to ensure that every dollar goes to those who need it most” and predicted it would save the budget $2 billion.

The kindest thing that can be said about what happened is that they didn’t follow through with the details, at considerable human cost.

It would be great to see something – anything – that made it look as if, five years on, they have learned from what happened.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.