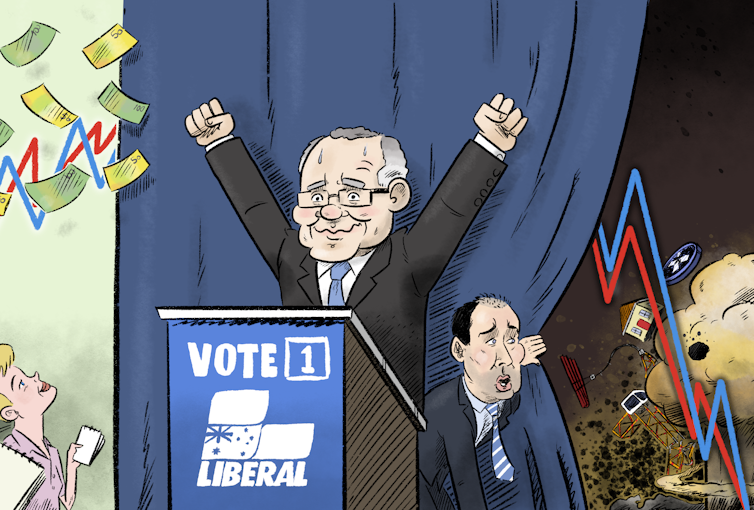

The Australian economy will remain healthy for long enough to enable the government to claim it as a strength in the lead-up to the May election, but the first Conversation Economic Survey points to a fairly flat outlook beyond that, with a 25% chance of a recession in the next two years.

The Conversation has assembled a forecasting team of 19 academic economists from 12 universities across six states. Among them are macroeconomists, economic modellers, former Treasury and Reserve Bank economists, and a former member of the Reserve Bank board.

Taken together their forecasts point to no recovery in the share market during 2019, no recovery in wage growth, no further improvement in the unemployment rate, further modest home price falls in Sydney and Melbourne, and to a budget deficit next financial year despite the official forecast of a surplus and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s commitment that the government will fight the election continuing to forecast a surplus.

Weighing heavily on Australia’s economy during 2019 will be a much weaker US economy, with what the forecasting team says is the possibility of a US recession, and weaker growth in China. Australian consumer spending is forecast to continue to grow during 2019, but no faster than it did during 2018. The best measure of living standards is forecast to advance at a crawl.

Most of the team expect the Reserve Bank to sit on its hands throughout all of 2019, leaving its cash rate unchanged at the all-time low of 1.5% for what will be a record 40 months.

Economic growth

The panel expects the Australian economy to grow more slowly in the year ahead, by 2.6%, down from recent annual growth of 2.8% and 3.1%. None of the panel expects growth to exceed 3%. One, Steve Keen, formerly of the University of Western Sydney and now at University College London, expects growth of only 1%.

Most of the panel expect China’s growth to continue to slow, from the annual growth of 6.7% typical over recent years to just 6.2%, the weakest growth since the 2008 global financial crisis and the weakest calendar year growth since 1990.

Former Treasury economist Nigel Stapledon now at the University of NSW nominates China as the biggest threat to Australian and global growth. He says it has a good record of stimulating its economy to get out of difficult corners but one day it might get it wrong.

The panel expects US economic growth to hold up at 2.8% during the year ahead but to weaken or go into reverse by year’s end as the “sugar hit” from the Trump tax cuts goes into reverse.

Former Treasury and International Monetary Fund economist Tony Makin points to US high public debt that will need to be rolled over, soaking up funds that could have been more productively used for investment, to higher US interest rates imposed by a central bank concerned about inflation, and to the escalating trade war with China.

ANU modeller and former Reserve Bank board member Warwick McKibbin says the US economy is “very likely” to begin to go backwards towards the end of the year. Craig Emerson, a former Australian trade minister now with Victoria University, says the US is likely to enter a recession in 2020. Former Treasury economist Mark Crosby at Monash University says if there is a US recession, it won’t hit until late 2019, with the impact greatest in 2020.

Rebecca Cassells from the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre says a lot depends on the outcome of the US-China trade war: “The two biggest economies are going head to head, but both are almost as reliant on the other to sustain their growth trajectories,” she says.

Australia should look to other parts of the world to drive its economic growth. “India is one of them, and is rising rapidly with no downgrading of its growth trajectory of 7.75% for 2019.”

Living standards

Nominal GDP, the money earned in Australia unadjusted for price changes, is forecast to grow more slowly in 2019, by 4.5%, down from recent growth in excess of 5%, reflecting weaker iron ore prices.

The best measure of living standards, real net disposable income per capita, is expected to barely grow, climbing just 1% over the year to December, much less than recent growth in excess of 3%, but much more than its performance in the dismal years between 2012 and 2016 when it went backwards.

Forecasts for the unemployment rate cluster around its present 5.1%, with only four below 5% and one above 6%.

Wages and prices

Wage growth is forecast to climb no further in 2019, finishing the year at its present 2.3% instead of climbing to 2.75% on its way to 3% by mid 2020 as forecast in the budget update.

Rebecca Cassells points out that much of the increase we have had has been driven by the Fair Work Commission’s decision to lift the minimum wage 3.5% from June 2018, suggesting very low growth elsewhere. Disturbingly, she says more and more enterprise bargains are being terminated, with employees falling back on awards.

Overwhelmingly, our panel is of the view that the only thing that will lift wage growth out of its slump (and budgets have been incorrectly forecasting a bounce out of the slump for eight years now) is higher productivity: producing more per worker.

Victoria University economic modeller Janine Dixon notes that the December budget update actually downgraded its forecast of productivity growth, from 1.5% to 1%, and so is not optimistic.

She says even if productivity growth did pick up, excessive market power in some industries combined with weakness in labour market institutions means it might not easily be passed on to workers.

Tony Makin, a supporter of company tax cuts, says the best thing to lift productivity would be new (perhaps foreign) investment embodying productivity-enhancing technology.

The saving grace for workers facing yet another year of historically-low wage growth is that price increases will also remain low.

Inflation has been right at the bottom of (or below) the Reserve Bank’s 2% to 3% target band for four years now, meaning that even at the continuing low rates of wage growth forecast, wages should continue to climb just faster than prices.

The panel expects consumer spending to climb by only 2.5% in real terms in 2019, most of which will reflect population growth of 1.6%.

The average forecast for inflation is at the very bottom of the Reserve Bank’s target band. Only two panel members expect inflation to edge back up to the middle of the band. They are Warwick McKibbin and former Treasury and ANZ Bank chief economist Warren Hogan, at the University of Technology Sydney.

Interest rates and the budget

Without either a lift in inflation or a substantial weakening in the economy there is little reason for the Reserve Bank to move interest rates in either direction.

Governor Philip Lowe took the job in September 2016, just after the board cut the cash rate to a record low of 1.5%. He hasn’t moved the cash rate since, although on several occasions he has said the next move is most likely to be up.

Five of the panel do expect at least move up this year, including the two who think inflation might approach the bank’s target. Three expect cuts, taking the rate below 1.5%.

The remaining eleven expect no change, all year.

The government says it will deliver a budget surplus next financial year, of A$4.1 billion, the first surplus in a decade.

The panel doesn’t think so, all but one member predicting a lower budget surplus than the government, and seven predicting deficits. The average forecast is for a deficit of A$3.5 billion rather than a surplus of A$4.1 billion.

Monash University macroeconomist Solmaz Moslehi identifies optimistic wage growth, weaker than expected mining investment and a hit to consumer spending from the housing downturn as the biggest risks to the forecast surplus.

Julie Toth, adjunct professor at Deakin University’s Master of Business Administration program and chief economist at the Australian Industry Group, says the latest indicators suggest that neither employment nor wage growth will accelerate by as much as the government expects.

Michael O’Neil from the South Australian Centre for Economic Studies says the biggest immediate risk to the forecast surplus is thermal coal prices, given China’s efforts to cut coal imports and the shift to renewables in China and India.

The biggest long term risk is the scale of the company tax cuts and the ongoing shift of income from highly-taxed labour to more lightly-taxed capital.

Margaret McKenzie of Federation University identifies the biggest risk to the surplus as a change of government, something she says she welcomes because with extensive idle capacity and underemployment, a surplus would be unhelpful.

Home prices

The panel expects Sydney home prices to fall by another 5.8% and Melbourne prices by another 5.1% in 2019, taking the slides over two years to 14.7% and 12.1%.

Only Macquarie University and former Reserve Bank economist Jeffrey Sheen expects prices to move back up throughout 2019, by 2% and 3%.

Reassuringly, none of the forecast falls are bigger than 10%. The biggest are predicted by Steve Keen, Tony Makin, Margaret Mckenzie and Craig Emerson.

The lower prices will be accompanied by much slower growth in housing investment, expected to climb only 2.1% in 2019 after climbing more than 7% in the year to September 2018.

Business

Non-mining business investment is forecast to grow more slowly this year, by 5.7% instead of 11.4%, and mining investment is expected to keep sliding, losing a further 3.4% after losing 11.2% last year rather than climbing as the government’s budget update predicts.

Five of the team believe that mining investment to turn the corner in line with the budget forecast. Nine expect it to fall further.

The Australian share market will for practical purposes not grow not at all during 2019 according to the average forecast, which is for barely perceptible growth of 0.1%. A steady share market would come as a relief to super funds and share owners after last year’s slide of about 7%.

The range of forecasts for the ASX 200 is wide, from slides of more than 6% to gains of more than 6%.

Markets

Fortunately for a government the panel expects to need to continue to borrow more in order run continued budget deficits, what it pays for to borrow via the 10-year bond rate is expected to remain little changed at 2.6%. Only Warwick McKibbin expects a much higher bond rate, of 3.5%.

The panel’s average forecast is for an broadly unchanged Australian dollar, of around 70.5 US cents. The highest forecast is for US$0.80, the lowest for US$0.62.

The iron ore price, at present close to US$74 a tonne, is expected to fall to around US$64. Only one panelist, Warwick Mckibbin, expects it to stay near where it is, at US$75. The government itself is cautious, using a price of US$55 in its budget forecasts, a number it might lift in the April budget, allowing it to forecast more revenue.

The risk of recession

On average, the panel believes there is a 25% chance of a conventionally-defined recession within the next two years.

Half of the probability estimates are between 20% and 30%. Averaging all of them together other than Steve Keen’s estimate of 95% produces an estimate of 22%.

A recession is conventionally defined as two consecutive quarters in which gross domestic product falls instead of rises. Australia hasn’t had two consecutive quarters of negative growth since 1991.

The most recent negative quarter was in September 2016. Before that there was one in March 2011, and before that in during the global financial crisis in December 2008.

Ross Guest of Griffith University makes the point that his estimate of 20% should be considered low. There will always be a risk of a recession. By itself two quarters of negative growth needn’t be a disaster. The impacts on the government and on consumer and business confidence would be more important than the downturn itself.

Guay Lim of the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research assigns the lowest probability of any of our panel to a recession, 5%, saying the most likely catalyst would be a global trade war.

Warren Hogan assigns the highest probability to a recession after Steve Keen, 40%, saying Australia is facing the end of a major construction boom and has heavily indebted households. It will be vulnerable to any negative shocks and especially vulnerable to higher inflation and interest rates.

Steve Keen says the only thing that has kept Australia afloat since the China boom has been the housing bubble, which the banking royal commission has been discovering was built on fragile, and in places fraudulent, foundations.

Nigel Stapledon says the biggest drag on the economy will be the collapse in the construction of residential investment units. Labor’s proposed increase in capital gains tax will make it worse, notwithstanding Labor’s decision to exempt new construction from its crackdown on negative gearing.

Rebecca Cassells says on the bright side Australia is set to become the world’s biggest exporter of liquefied natural gas, the biggest exporter of iron ore to India and the world’s biggest producer of lithium, needed for batteries.

And if there is a global economic downturn within the next few years, she says another positive is that Labor is likely to be in power, making the successful deployment of a stimulus package more likely than if the Coalition had been in office.

Link to pdf of results spreadsheet

Age and Sydney Morning Herald economic survey here

.The Conversation Economic Panel

Click on economist to see full profile.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article.