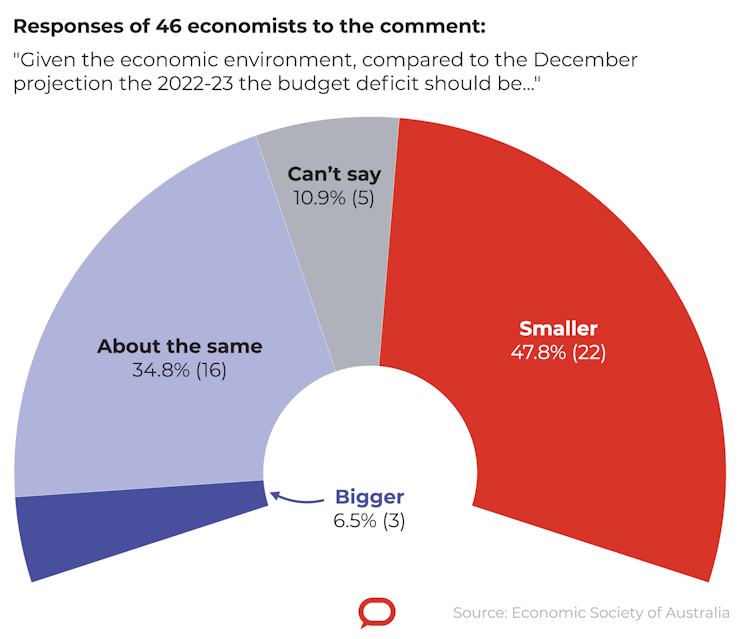

So good, and so unexpected, has been Australia’s economic improvement over the past three months, it has wiped one-third of the projected 2022-23 budget deficit. Or it would have, had the government not decided to give away almost half (45%) the windfall.

That’s one way of looking at the difference between the projections in the December budget update and those presented three months later in Tuesday’s March budget. In December, the deficit for the coming financial year was to be A$98.9 billion.

Three months later, the budget papers say it would have been $38 billion lower, were it not for an extra $17.2 billion of spending and tax measures taken since the update and in the budget.

The measures leave the 2022-23 budget deficit at $78 billion, something set to shrink to $43 billion over the following three years, but with no help from savings in this budget.

The budget measures expand the deficit in each of the five years for which the government provides projections, by $30.4 billion in total.

Working the other way, improved economic circumstances shrink the deficit by $114.6 billion.

It’s a convenient way to examine the projections, but it’s unfair. Most of the improvement due to economic circumstances is the government’s own work.

An astounding $98.5 billion of the $114.6 billion improvement is because Australia’s extraordinary and unexpected success in driving unemployment down to a near 50-year low, with a further improvement forecast in the budget.

It is helping the budget in two ways. The government is spending much less than it expected on JobSeeker and Youth Allowance, and taking in more than expected in income tax from people it hadn’t expected to be in work.

It’s what former finance minister Mathias Cormann insisted would happen in 2020 when the first COVID budget threw the switch to massive spending.

By throwing everything it could at keeping people in work through programs such as JobKeeper, the government would “grow the economy” and grow tax revenue to push down the resulting government debt as a proportion of GDP.

The budget papers show it happening.

A year ago, net debt was expected to peak at 40.9% of GDP in mid-2025 before sliding as the economy grew. Now it is expected to peak earlier at 33.1% of GDP.

Net interest payments are expected to peak at a very small 0.9% of GDP in 2025-26 before slipping to 0.8% of GDP.

And there are reasons to think things will turn out better than forecast.

Unemployment, now down to 4%, is expected to fall only a little further to 3.75% within months and then stay there before climbing back to 4% in 2026.

But that’s because treasury has assumed unemployment can’t stay as low as 3.75% without sparking inflation – an assumption it concedes might be wrong, noting Australia has “limited recent experience” of an unemployment rate lower than 5%.

Forecasts conservative

Treasury has assumed the iron ore price, at present US$134 a tonne, falls back to US$55 in coming months. It has assumed the coking coal price falls from US$512 a tonne to US$130, the thermal coal price from US$320 a tonne to US$60 and the oil price from US$114 a barrel to US$100. Every one of these assumptions looks conservative.

Frydenberg admitted as much in the budget press conference, saying if commodity prices merely stay put for just the next six months instead of falling as assumed, the budget will be $30 billion better off.

About the only forecast that doesn’t look conservative is the one for wages growth.

At present an embarrassingly low 2.3%, the budget forecasts a jump in annual wages growth to 2.75% within months followed by a jump to 3.25% in 2023 and to 3.5% by June 2025.

The forecasts conveniently put wages growth back above forecast inflation of 3% in 2022-23, leaving Australians with only one more year in which the buying power of wages goes backwards.

In the budget fine print (page 60 of Statement 1) treasury concedes it’s none too sure about its forecast of wages growth we haven’t seen in a decade. It shares an alternative forecast that uses different assumptions to produce annual wages growth no higher than 2.5% – below inflation for a further two years.

Support measures (mostly) well designed

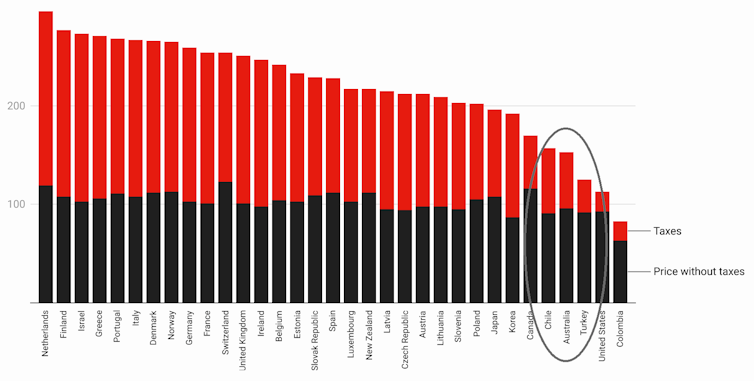

The cost-of-living measures are well-designed (with the exception of the six-month cut in petrol excise that will benefit most the high earners who typically spend the most on petrol). The one-off payment of $250 to Australians on benefits will go to those who do need it.

And the one-year boost of $420 to the low- and middle-income tax offset (bringing it to as much as $1,500) will only be available to Australians earning less than $126,000. They will get it after they put in their tax return from July – when they are most likely to need it – and then no more. It isn’t being continued.

Frydenberg has spent big in 2022 – but on the whole, responsibly. The budget forecasts and the unemployment numbers show his COVID support spending in 2020 and 2021 has paid dividends. They are forecasts for the true believers.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.