During the election campaign then-opposition leader Bill Shorten repeatedly claimed that everything was going up.

“Childcare is up 28%, out of pockets to see the doctor up 20%, specialists … up nearly 40%,” he said. And then the punchline: “everything is going up, except your wages.”

Statistically, it wasn’t true. The official rate of inflation was just 1.3%. The official rate of wage growth was 2.3%.

I haven’t asked him, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he kept saying it because his focus groups told him that’s what people felt.

Today’s release of the 17th wave of Australia’s Household, Income and Labour Dynamics Survey (HILDA) tells us that despite the official statistics, people were right to feel they were going backwards.

Funded by the Australian government and managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, HILDA is one of the most valuable tools Australian social researchers have.

It examined the lives of 14,000 Australians in 2001 and then kept coming back to them each year to discover what had changed. By surveying their children as well, and in future surveying their children, it will be able to build up a long-term picture of how circumstances change over the course of lives and generations.

It can be thought of as Australia’s Seven Up!, the British TV series that keeps going back for updates on the lives of 14 children it first examined when they were seven. Except that HILDA’s results have statistical significance, and the questions are detailed, asking among other things about depression and anxiety, work-life stress, stress in relationships, and illicit drug use.

We are right to feel no better off…

The Australian Bureau of Statistics does indeed find that wages are climbing faster than prices, as they almost always have, but because it doesn’t examine what happens to a particular household over time it can tell us little about whether an individual’s experience of things is getting better or getting worse.

HILDA gets a handle on each household’s disposable income by asking each member of the household about their gross income from wages, benefits, investments and other sources and then deducting its estimate of taxes. It gets a handle on the real (inflation-adjusted) changes by adjusting its totals for changes in the consumer price index.

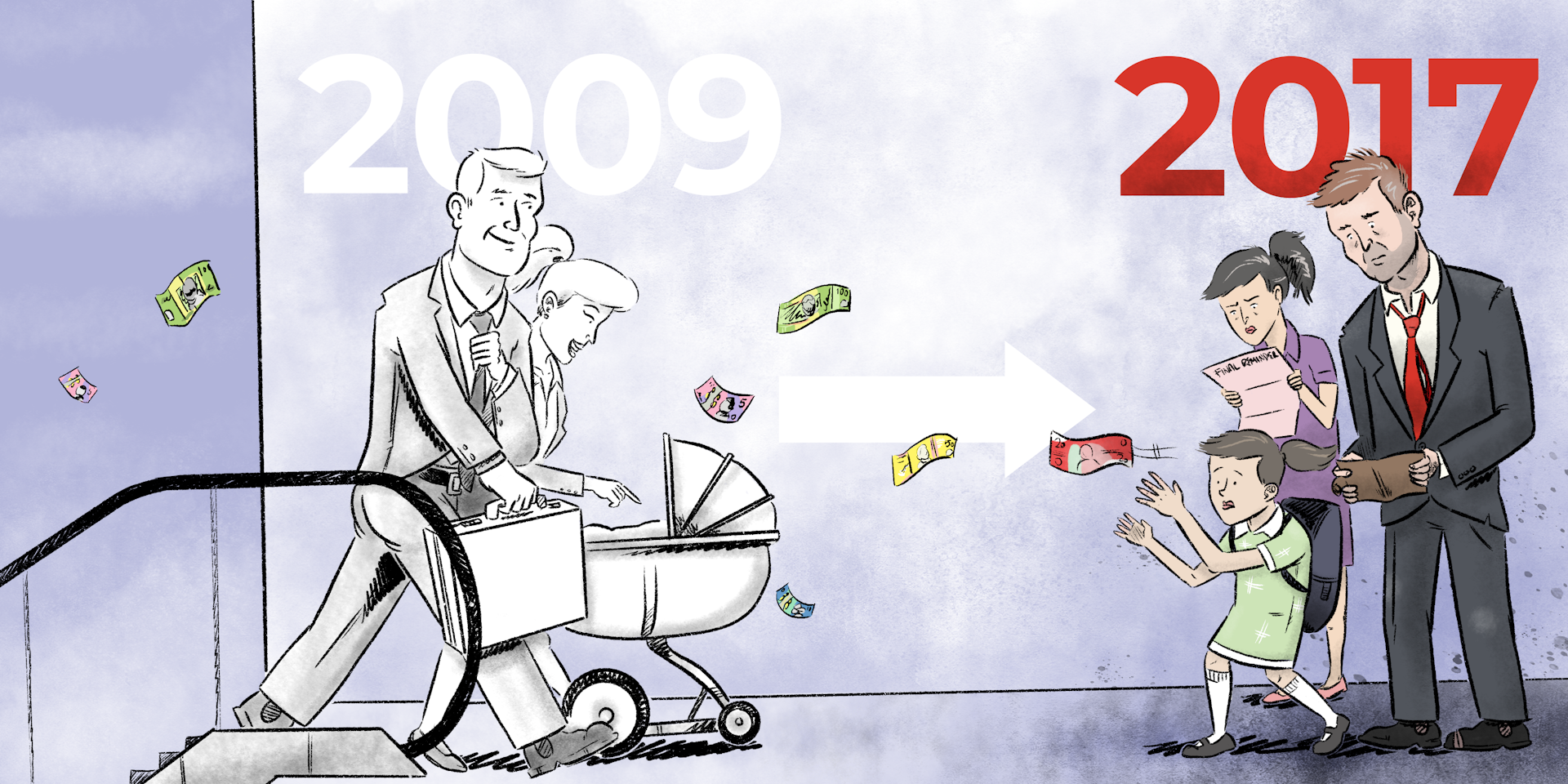

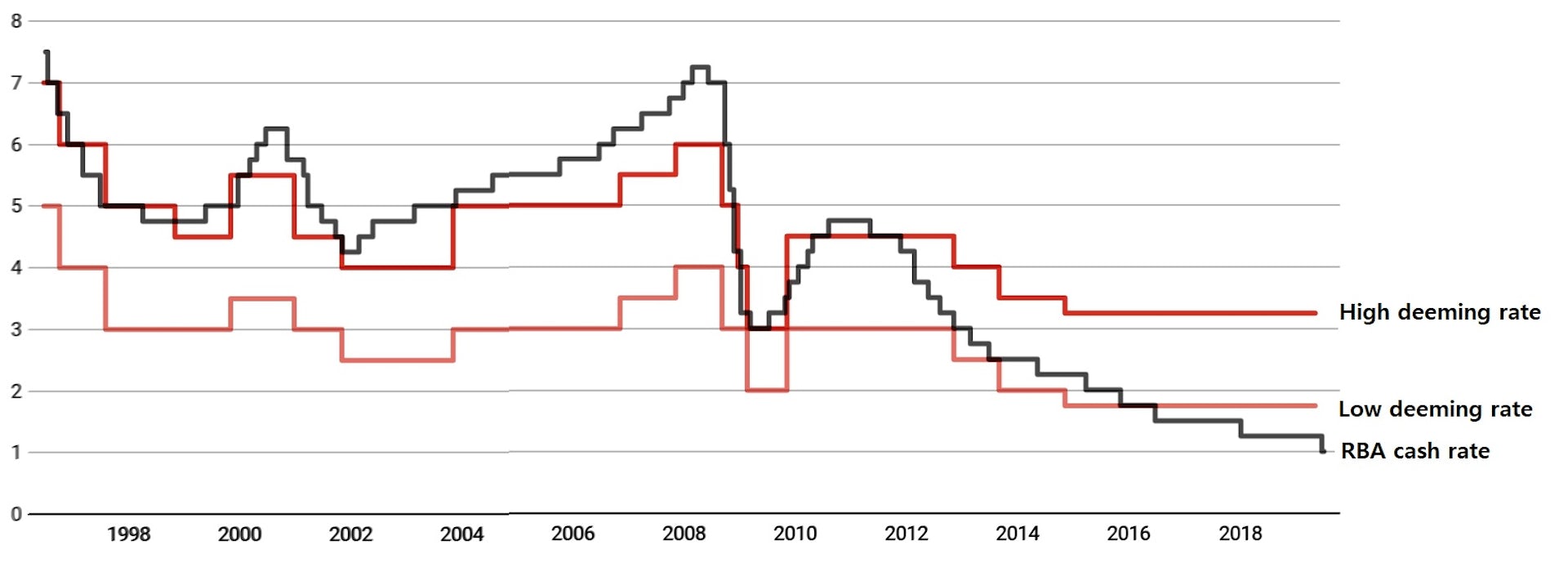

It finds that for the thousands of households it interviewed, real disposable income grew strongly during the first nine years of the survey, between 2001 and 2009. Then, after the global financial crisis, for the eight years between 2009 and the 2017 results released today, that growth stalled.

Expressed in today’s dollars, the average annual real disposable income of those households climbed by A$19,773 between 2001 and 2009, about $2,472 per year.

But most of the growth was during the mining boom that stretched from 2003 to 2009 when the average annual real disposable household income climbed about $3,000 per year, as did the income of the more representative median (or middle) household.

Since 2009 and the global financial crisis, the average and the median have moved in different directions.

The average houshold’s annual real disposable income has climbed a further $3,156. The median (or typical) household’s income has fallen $542, although not steadily. The graph shows it falling between 2009 and 2011, climbing in 2012, and changing little thereafter.

…and as if it’s harder to get ahead…

It has also become harder to “get ahead”, in the phrase used often by the prime minister.

Between 2001 and 2005, 40% of the households in the bottom fifth of earners (the bottom qunitile) moved out of it into a higher one. In more recent years, between 2012 and 2016, a lower 38.5% moved up.

Between 2001 and 2005, 44% of the households in the top qunitile had to move down to let other households take their place. In more recent years, between 2012 and 2016, only 41.5% have moved down.

Getting a long way out of the income circumstances you were born in is a long-shot, according on HILDA’s early attempt at measuring intergenerational mobility.

People who were 32-34 years old in 2015-17 are highly likely to be in the same household income quintiles as those people found themselves in when they were 15-17 back in 2001-03.

There’s only a one in ten chance of moving from the bottom quintile as a teenager to the top quintile in your early thirties. There’s a 37% chance you’ll stay put.

Even among teenagers who grew up in the middle quintile, there’s only a 17% chance of making it to the top, along with a 19% chance of moving one rung up.

Interestingly, women turn out to be more tied to the income their families had when they were children than men, and both men and women tend to stay more closely tied to their mother’s income than their father’s.

…yet we are less reliant on welfare, even pensions…

When HILDA began in 2001, 39% of Australians aged 18 to 64 were living in a household that received government welfare of some kind. By 2017, that proportion had fallen to 31%, but almost all of the drop happened before the global financial crisis in 2009.

Most of us are still in households that have received something from the government over a 10-year period: 58% of working age Australians in 2017, down from 64% in 2010.

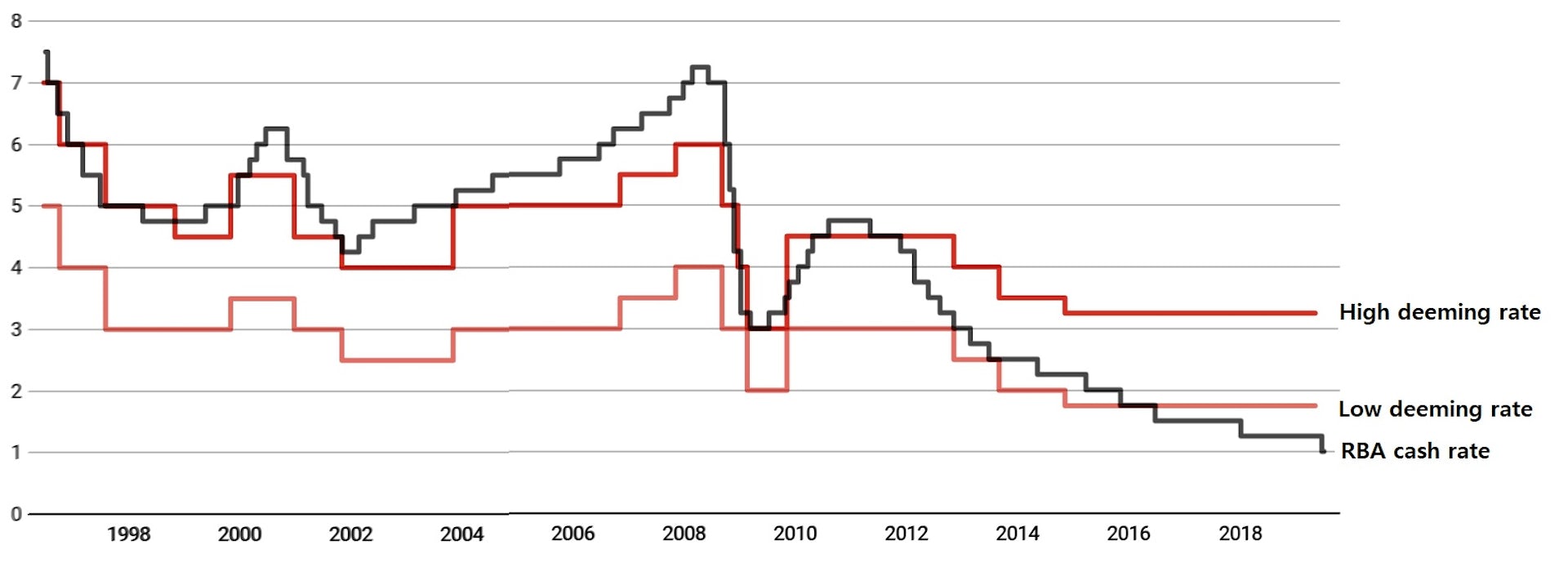

Among older Australians aged 65 and over, reliance on the age pension and other benefits for more than half of income needs has dropped from 60% to 51%.

Among new retirees aged 65 and over, the proportion receiving the age pension has fallen from 76% of men and 74% of women to just 60% of men and 55% of women.

Read more: More people are retiring with high mortgage debts. The implications are huge

But while the growth of compulsory superannuation is likely to be part of the story, almost all of the decline happened before the financial crisis in 2009, suggesting that the destruction of wealth in the crisis kept people on the pension who otherwise might not have needed it.

…and gender roles are changing

Before the financial crisis, almost three quarters (73%) of men of traditional working age were employed full-time. After the crisis, the rate slipped to a much lower 67% and stayed there.

Female full-time employment was also hit by the crisis but has since almost totally recovered to be just a fraction below its pre-crisis peak of 39.6%.

Women’s hourly earnings are also climbing faster than men’s, up 24% between 2001 and 2017, compared to 21% for men’s.

While women have always been more likely than men to be employed casually, since the crisis male casual employment has climbed while female casual employment has declined.

The two are now as close as they have ever been, with women now only six percentage points more likely than men to be employed causally.

In dual-earner male-female couples, the proportion in which the woman earns more than the man has climbed from 22% to 25%.

The woman being the main breadwinner is more common in couples that aren’t legally married and don’t have children. It is also far more common in the regions than in cities and among couples in which the man doesn’t have a university degree.

Men in predominantly female breadwinner households are somewhat less happy with their lives and with their relationships, as (perhaps surprisingly) are women.

Fathers tend to agonise more about work-family conflict than mothers, notwithstanding the much greater amount of housework and childcare work performed by mothers. The men who worry the most work long hours, have irregular shifts and very young children. A mother working the same hours as a father will typically be more conflicted.

Read more: Language of love: a quarter of Australians are in inter-ethnic relationships

Most parents suffering high work-family conflict get out of it within a year or two, often by managing things better and sometimes by changing jobs. Those suffering high work-family conflict are 50% more likely than others to separate the next year.

HILDA’s great strength is that it will be able to follow those parents and their children and all the other families it surveys and tell us what happens next. Rather than being an Australian version of Seven Up!, it might be better described as Australia’s never ending story. Its co-director Roger Wilkins says its design allows it to be “infinitely lived”.

Read more:

Australian city workers' average commute has blown out to 66 minutes a day. How does yours compare?

![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.