Australian economists overwhelmingly back social distancing measures that slow the spread of coronavirus over the alternative of easing restrictions and allowing the spread of the disease to pick up.

But a significant minority, 9 of the 47 leading economists polled in the first of a series of monthly surveys, say they would support an easing of restrictions even if it did allow the spread to accelerate.

The Economic Society of Australia-Conversation monthly poll will build on national polls conducted by the Economic Society, initially in conjunction with Monash University, since 2015.

The economists chosen to take part are Australia’s leaders in fields including microeconomics, macroeconomics, economic modelling and public policy. Among them are former and current government advisers and a former and current member of the Reserve Bank board.

Their responses are given weight by statements explaining their views published in full on The Conversation website and by a requirement that they rank the confidence they have in their responses on a scale of 1 to 10.

What matters is R

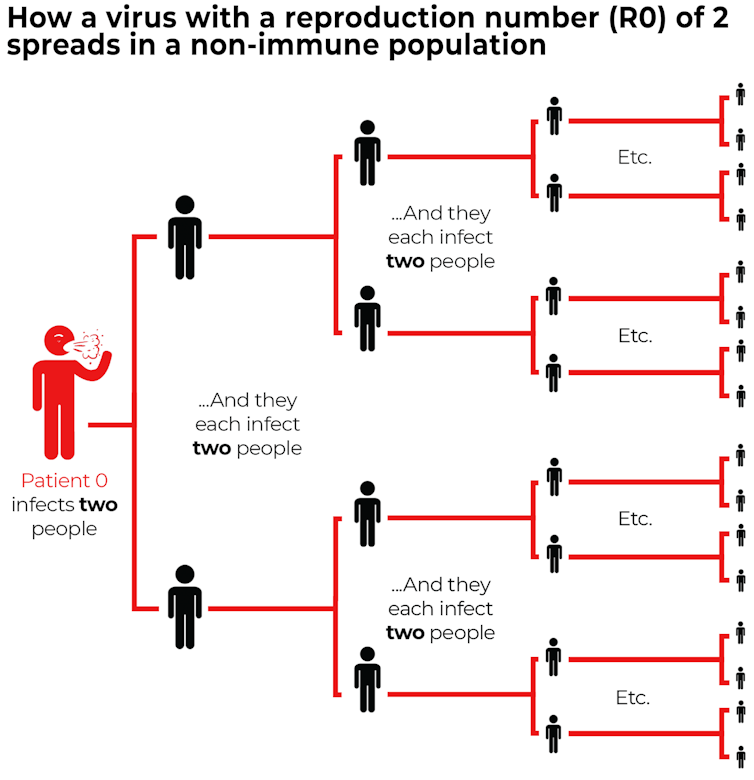

R, which is also referred to as R0, R₀, and Rt is the reproduction number of the virus. It a measure of the average number of other people that any person with it will directly infect.

An R of 2 means that on average each person with the virus will directly infect two other people in a process that will escalate increasingly quickly until after four sets of contacts 16 people have it, and after 20 sets of contacts more than one million people have it.

This snowballing effect is a property of any R above 1.

At an R below 1 the spread decelerates until very few people have it.

In the early days of the outbreaks, Australia’s value of R was well above 1.

The lockdowns and other restrictions have helped push it down to about 1.

The 47 leading Australian economists selected by the Economic Society of Australia were asked whether they agreed, disagreed, or strongly agreed or strongly disagreed with this proposition:

The benefits to Australian society of maintaining social distancing measures sufficient to keep R less than 1 for COVID-19 are likely to exceed the costs.

The proposition suggests that in the present context it is likely to be worthwhile to continue to maintain the restrictions that are needed to push R below 1 and keep it there.

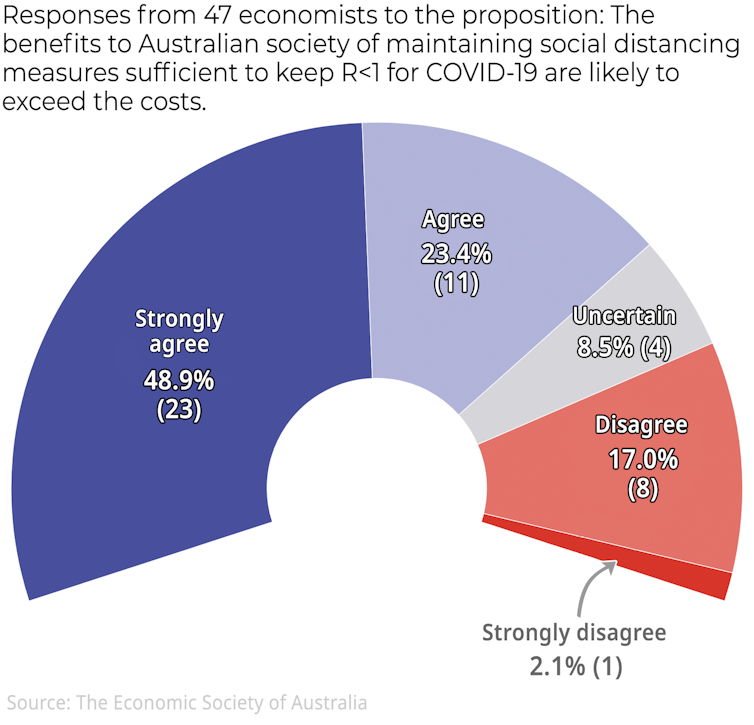

Almost three quarters of the economists surveyed – 34 out of 47 – backed the proposition, 23 of them “strongly”.

Only nine disagreed, and only one strongly.

The arguments put for the worth of maintaining social distancing measures sufficient to keep R below 1 include avoiding “tens or hundreds of thousands of avoidable deaths” (John Quiggin) and allowing the economy to return to normal sooner than otherwise by escaping the need for “repeated lockdowns” that might be needed if the disease got out of control again (Ian Harper).

Chris Edmond uses the analogy of the Phillips Curve that is meant to show the the tradeoff between levels of inflation and unemployment.

Although it shows a tradeoff in the short term (more inflation results in lower unemployment) in the longer term it finds no such tradeoff. More inflation simply leads to higher prices with unemployment being no lower.

Read more: Eradicating the COVID-19 coronavirus is also the best economic strategy

“In a similar way, there is no long-run trade off between public health and the health of the economy in responding to the COVID-19 crisis,” he says.

Lifting restrictions “risks the worst of all worlds, compromising our public health goals and at the same time not getting a proper economic recovery”.

Stefanie Schurer quotes a German proverb: better a painful ending than an endless pain.

Lifting restrictions “worst of all worlds”

She says a short and medium term failure to eliminate, or at least slow down, the spread of COVID-19 would entail significant longer-run political, economic and social costs.

Renee Fry-McKibbin points out that that even if the deaths from reopening economic activity turn out not to be high, we have no idea yet of the long term health consequences of exposing more people to COVID-19.

“Will people suffer from respiratory issues going forward requiring ongoing medical attention?” she asks. “We have incomplete information on the actual costs and benefits.”

Saul Eslake, who can see the worth of continued restrictions that keep R below 1, cautions that the longer they remain in place, the more the case for reopening will grow.

Yet the costs of restrictions are growing

Craig Emerson says keeping R below 1 should be merely a “guiding principle” rather than a binding constraint.

“The longer the restrictions are in place, the greater will be the likelihood of links being broken - leading to severe economic hardship, business failures, mortgage defaults, domestic violence, mental health problems, suicide and long-term unemployment, particularly for the young,” he says.

Gigi Foster says, in retrospect, the best thing for Australia to have done would have been to have never had an enforced lockdown, but to have encouraged people to continue to behave as normally as possible while taking precautions, as in Sweden, allowing young and healthy people to acquire immunity in order to protect more vulnerable people, in this and in future waves of the virus.

She suspects the costs of continued restrictions that keep R below 1 outweigh the benefits, including benefits measured in quality-adjusted life years saved.

Read more: COVID lockdowns have human costs as well as benefits. It's time to consider both

Hugh Sibley says that by making progress towards eliminating the virus we have eliminated the option of acquiring the mass immunity that would make it easier to live with it.

“We have, in effect, dug ourselves into a hole,” he says. “And we are now congratulating ourselves how deep that hole is. Too few people are asking how we get out.”

Supporters more certain than opponents

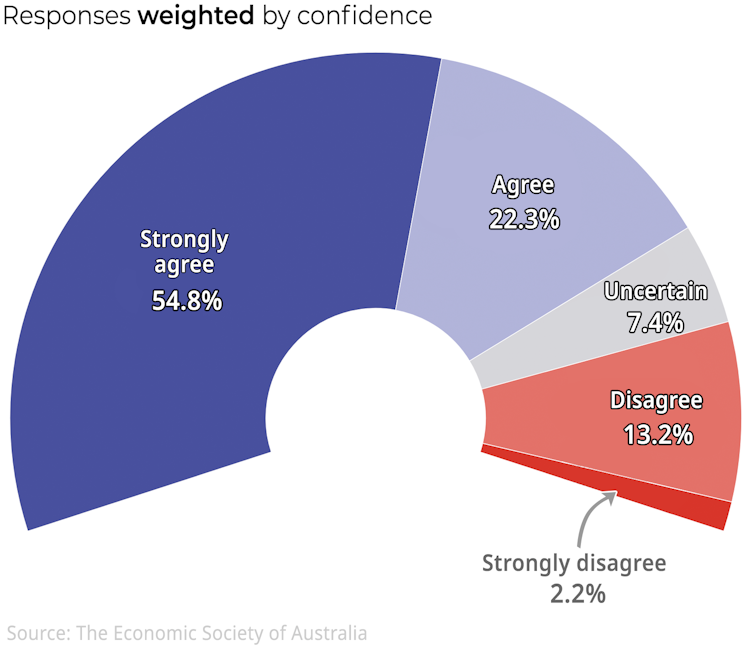

When responses to the survey are weighted by the confidence respondents have in them, opposition to restrictions weakens.

Unweighted for confidence, 19% of respondents oppose the proposition that restrictions that keep R below 1 are likely to be value for money.

Weighted for (lack of) confidence, opposition falls to 15.4%.

Unweighted for confidence, 72.3% support the proposition that restrictions that keep R below 1 are likely to be value for money.

Weighted for confidence, that support grows to 77.1%

The proportion strongly agreeing with the proposition grows from 48.9% to 54.8%

Put another way, when weighted for confidence, a clear majority of the economists surveyed strongly support the proposition that the benefits to society from maintaining social distancing measures sufficient to keep R less than 1 are likely to exceed the costs.

Individual responses

![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.