The Deficit Myth: How to Build a Better Economy

Stephanie Kelton, Hachette Australia

No book prepared ahead of time better targeted the year in economics.

Just as governments including Australia’s were embracing debt (A$800 billion and counting) and creating money out of nowhere ($200 billion scheduled) came a treatise explaining that at times like these (actually, at any time when the resources of the economy aren’t fully employed) that’s entirely responsible.

Stephanie Kelton’s book has rightly been displayed on Alan Kohler’s desk, and Kohler himself has become a convert to modern monetary theory which the book outlines in the clearest of terms.

Kelton explains that in an economy such as Australia’s the purpose of tax isn’t to raise money but to slow spending, and something else: demanding the payment of tax in Australian dollars forces Australians to use Australian dollars.

The example of teenagers not cleaning up around the house that she used in her talk at Adelaide University in January is priceless. You can watch the video here.

Economics in the Age of COVID-19

Joshua Gans, MIT Press

Written as we were coming to grips with what to do, and posted online chapter by chapter to get real-time feedback, the Australian author’s flash of inspiration was that we have experience in shutting down an economy and then restarting it.

We do it every Christmas writes Joshua Gans, and “no-one screams depression”.

That his way of seeing things now dominates talk about the pandemic doesn’t make it less radical. It’s partly because of his insights, published in April, that most governments no longer think that in this crisis they can trade off health against wealth.

He persuades by analogy. Fans of Mission Impossible II, the computer game Plague Inc and the came of chess will appreciate the references.

Radical Uncertainty

Mervyn King, John Kay, Hachette Australia

The idea that every possibility can be reduced to a number, to a probability, is what makes simple mathematical economics work. It’s what makes insurance and credit ratings and assessments of the risk of getting coronavirus work. And it is wrong, as became clear in the devastation caused by the global financial crisis.

By itself, that’s not a particularly useful observation, but what is useful is the author’s discovery of where the idea that probability could be reduced to a simple number came from. The Nobel Prize winning economist Milton Friedman shares much of the blame. He insisted that every uncertainty could be reduced a number that a rational utility-maximising human being could use to make decisions.

Before Friedman and contemporaries, there used to be two numbers, one representing risk, and the other representing uncertainty, which are quite different things and can’t be thrown together.

If you’re too busy for the book, try the London School of Economics podcast.

Fully Grown: Why A Stagnant Economy Is A Sign Of Success

Dietrich Vollrath, University of Chicago Press

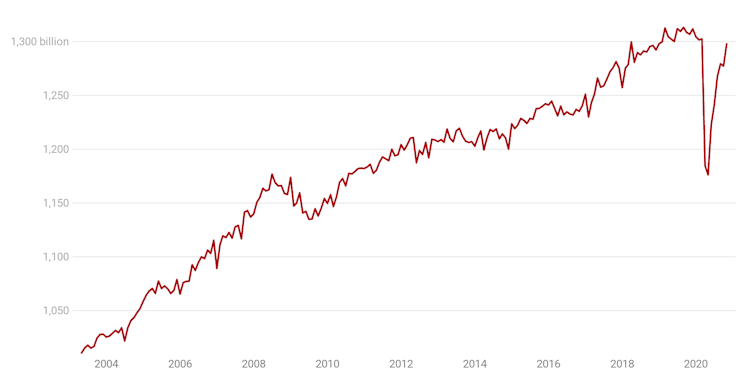

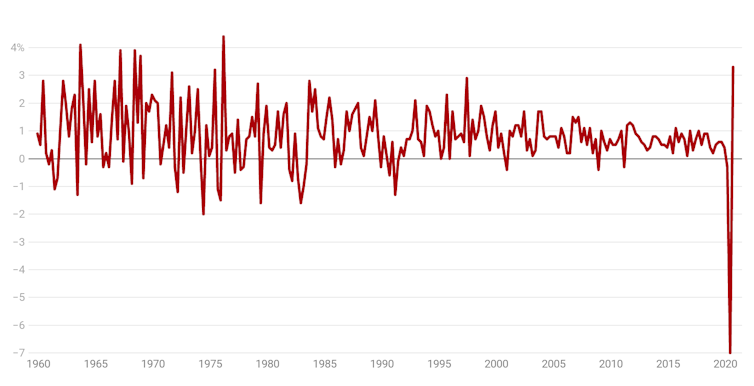

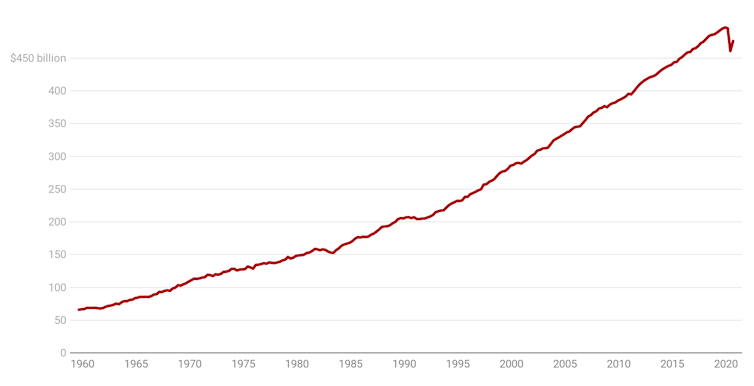

Advanced economies may or may not roar out of the recession, but they are unlikely to boom as they did before. For decade after decade throughout the 1900s annual economic growth has been strong, averaging 2% per capita in the US.

In the first two decades of the 2000’s that growth has been weak, averaging 1% – only half of what it did.

Dietrich Vollrath, who blogs on growth and had no preconceptions, approached the puzzle as a mystery and found that the usual suspects (rising inequality, slower innovation, competition from China) didn’t explain enough.

The extra comes from success. The populations of the US and kindred nations have become so rich and (on average) old that having more children and striving for even higher incomes no longer makes sense.

The technical stuff is at the back. The message from the front is that we’ve arrived at our destination, which needn’t be a bad thing.

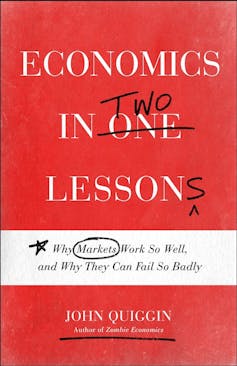

Economics in Two Lessons

John Quiggin, Princeton University Press

I’ve slipped this one in from 2019 for a reason. John Quiggin is about to publish a sequel, The Economic Consequences of the Pandemic.

Economics in One Lesson, published in 1946 financial journalist Henry Hazlitt, was a homage to the power of prices in a free market.

In lesson one (the first half of the book) Quiggin teases out Hazlitt’s thinking, and in lesson two shows how it follows from it that in many circumstances the market has to be contained.

Central to both lessons is opportunity cost, “what you give up in order to get something”, the most important concept in economics.

Polluters will make the wrong decisions if the cost of their pollution (largely borne by others) isn’t charged for. It’s a persuasive and increasingly-pressing argument.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.