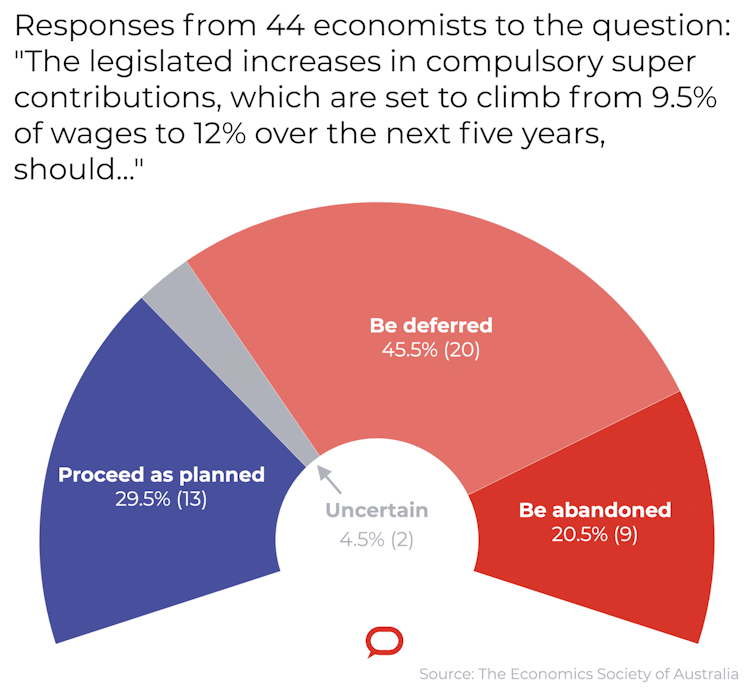

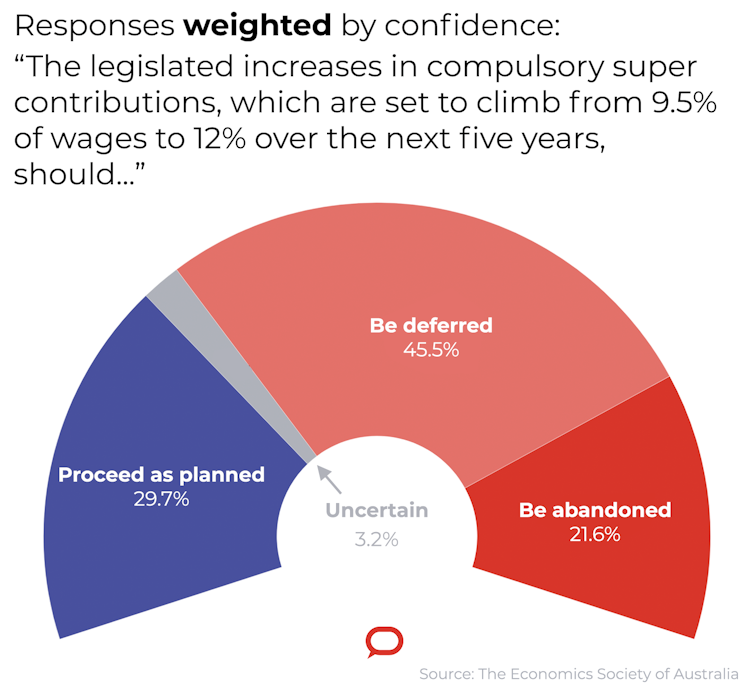

The five consecutive hikes in compulsory super contributions due to start next July should be deferred or abandoned in the view of the overwhelming majority of the leading Australian economists surveyed by the Economic Society of Australia and The Conversation.

Two thirds – 29 of the 44 surveyed – want the increases deferred or abandoned. Only 13 think they should proceed as planned.

An even larger majority, including some economists who want the increases to proceed, believe they will hit wage growth. Several are concerned they will hit employment.

Compulsory superannuation contributions are paid by employers.

But ahead of the most recent increase in compulsory super, from 9% of salaries to 9.5% in 2013 and 2014, the then Labor superannuation minister Bill Shorten said the increase would cost employers nothing because it would be taken from wage rises.

|

“A portion of what would have been employees’ increases will go into compulsory savings,” he said.

That conventional wisdom has since been challenged in work funded by the superannuation industry and has been examined extensively in the retirement income review at present with the government.

The two most recent increases in compulsory superannuation in 2013 and 2014 were small by design – 0.25% of salary each.

The next five increases, originally due to due to begin in 2015 but postponed to start in July 2021, are much bigger – 0.5% of salary each – at a time when wage growth is much smaller.

In 2012 Shorten was expecting wage increases of 3-4% and “assuming that a quarter of a per cent of that 3% to 4% may well go into your compulsory savings”.

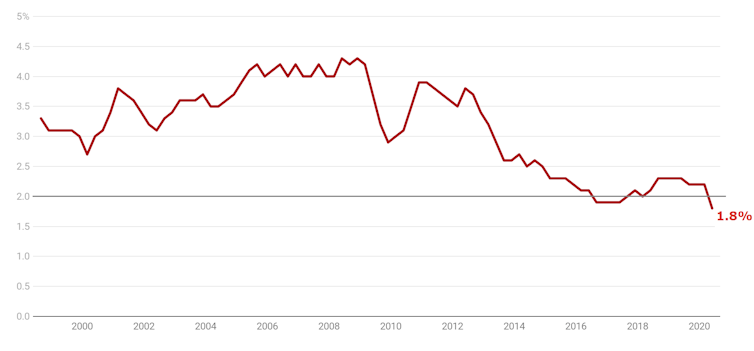

Wage growth has since slipped to 1.8%, the lowest on record. If the best part of 0.5% is taken out of that each year for the next five years it is unlikely to climb.

Wage growth has slipped to 1.8%

The 44 members of the Economic Society’s 57-member panel who responded include Australia’s preeminent experts in the fields of microeconomics, macroeconomics economic modelling, labour markets and public policy.

Among them are former and current government advisers and a former head of the Australian Fair Pay Commission and member of the Reserve Bank board and a former member of the Fair Work Commission’s minimum wage panel.

Read more: 5 questions about superannuation the government's new inquiry will need to ask

Each was asked whether the legislated increases in compulsory super contributions should proceed as planned, be deferred or be abandoned.

Only 13 of the 44 thought the increases should proceed as planned. 29 thought they should be deferred or abandoned, nine of them preferring they be abandoned altogether.

Those who thought they should be deferred argued that now is “not a time to encourage saving”. In the current circumstances we should be “far more worried about spending power today than in the golden years of present-day workers”.

Economist Saul Eslake said he had changed his mind. The latest evidence (which will be updated in the retirement income review) suggests that the current 9.5% so-called super guarantee will be enough to provide most people with an adequate income in retirement .

“In saying that I acknowledge that there is still a significant problem with regard to the adequacy of superannuation savings for women relative to men, but I don’t see how raising the super rate for everyone to 12% solves that problem,” he said.

“Not a time to encourage saving”

Economic modeller Janine Dixon said it was not clear that the optimal contribution was 12% rather than 9.5%. The increase would force some households into greater debt. While this would pose a risk to economic stability at any time, Australia could “not afford to let the household sector weaken further at present”.

Economist Geoffrey Kingston said anyone who felt 9.5% was not enough remained “free to make voluntary contributions”.

Among those believing the increases should proceed as planned were two former politicians, Labor’s Craig Emerson and former Liberal leader John Hewson.

Emerson said 9.5% was “considered inadequate by the burgeoning retiree population”. Without an increase, that population “would successfully demand increased pension levels from the Commonwealth”.

Opponents more confident

Hewson said compulsory super had become a fundamental part of an effective retirement incomes strategy and, COVID and economic collapse notwithstanding, we should “finish the job”.

Sue Richardson, a former member of the Fair Work Commission’s wage panel, believed any deferral might lead to another deferral and be “hard to recoup”.

The economists were asked to rate their confidence in their responses on a scale of 1 to 10.

Unweighted for confidence, 20.5% of those surveyed wanted to abandon the increases altogether. When weighted for confidence, that proportion climbed to 21.6%. The proportion that wanted the increases either deferred or abandoned climbed to 67.1%

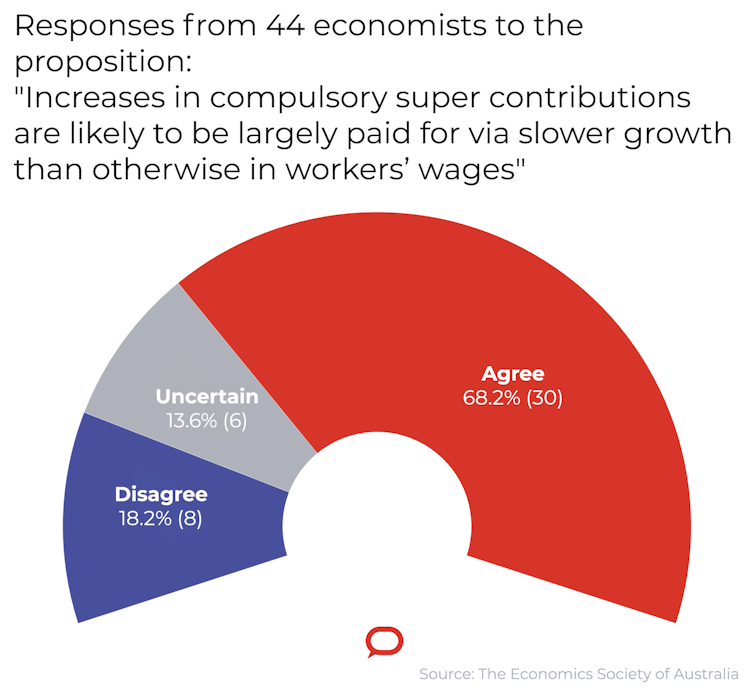

Asked whether the increases were likely to be largely paid for via slower wage growth than otherwise, 30 of the 44 economists agreed. Only eight disagreed.

Economist Nigel Stapledon said this “should not be controversial”.

Private sector economist Michael Knox said: “unless one lives in an unreal world, increases in superannuation guarantees are funded by employers out of the total wage the worker might otherwise receive”.

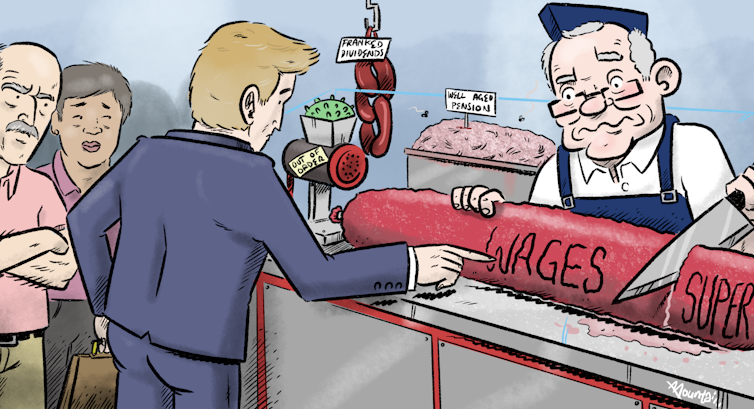

Super and wages come from the same pool

Several enterprise bargains explicitly make a trade-off between wages and superannuation, providing for wage increases that will be 0.5 points higher should compulsory super contributions not climb by 0.5 points.

Economist Alison Booth said if employers weren’t able to trim wage rises to pay for the scheduled increases in super contributions, they might “attempt to adjust on other margins”.

In a recession, when workers lack bargaining strength, “employers could coerce them to accept other adjustments to their contracts”.

Two of the eight economists who disagreed with the proposition that the increases in compulsory super would come at the expense of wages thought that employers wouldn’t grant wage rises anyway. Increases in super contributions might be one way for employees to get something.

A concern among both those who agreed and disagreed was that if the increase didn’t come at the expense of wages, it would push up the cost of hiring and come at the expense of jobs.

“Inflation is very likely to be very, very low and wages to be sticky,” said government advisor Matthew Butlin.

A drag on jobs if not wages

“Higher superannuation payments in an environment where wages are unlikely to rise and cannot fall will raise real labour costs and reduce the incentive to employ.”

Economic modeller Janine Dixon said that while over time the increase in contributions would probably come from wages, the immediate impact would be to increase the cost of hiring, “which is an unacceptably large risk in the present climate”.

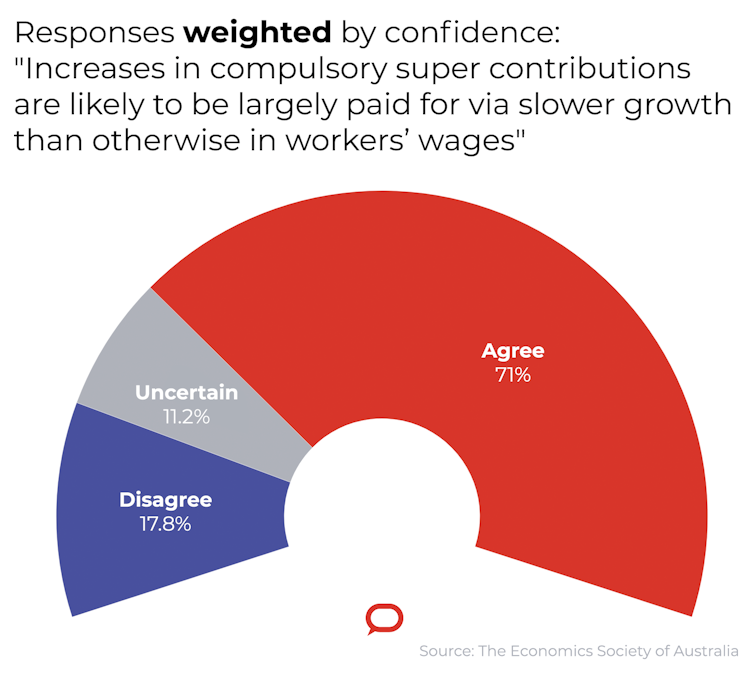

When adjusted for confidence, the proportion of those surveyed expecting the increases to largely paid for via slower wage growth climbed from 68.2% to 71%. The proportion disagreeing fell from 18.2% to 17.8%.

Individual responses

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.