Australia’s leading economists have struggled to grade this month’s budget.

Challenged by the Economic Society of Australia and The Conversation to rate it on a scale of A to F when judged by its stated aims of rebuilding the economy and creating jobs, none of the 43 economists who responded gave it the lowest grades of E or F.

But most who gave it a pass were unhappy.

Financial markets expert Kevin Davis praised “the willingness of a conservative government to adopt needed large deficit spending at variance with its ideology”.

Economic modeller and former Reserve Bank board member Warwick McKibbin said he would give it an A for scale.

But Davis said tax cuts “to the better-off employed” weren’t the best way of achieving desired outcomes, and McKibbin said the composition could have been much better designed.

Read more: It's not the size of the budget deficit that counts; it's how you use it

“There was an opportunity to invest in green infrastructure as part of a fiscal response and a climate/energy policy response that would have longer-term economic and environmental payoffs,” McKibbin said.

“For spending support, transfers to low income households rather than income tax cuts would have given a bigger bang for the buck. Greater support of childcare would support incomes and labour supply.”

Bob Breunig said the design of the childcare benefit created a well-documented income cliff for second earners making it difficult for them to work more hours. It was a known problem and would have been easy to fix.

Hard hats instead of soft skills

The Grattan Institute’s Danielle Wood said it was “absolutely the right call to change course on fiscal strategy and recognise the need for sizeable stimulus, so marks for that”.

But the budget “very much bet the house on a private sector-led recovery”.

Where it had spent money directly it mostly went to “hard-hat” professions such as infrastructure, construction, manufacturing, defence, utilities and energy.

Read more: High-viz, narrow vision: the budget overlooks the hardest hit in favour of the hardest hats

“Some of these sectors haven’t even seen job losses during COVID,” Wood said, and there is already a healthy pipeline of work for transport infrastructure projects, so why spend your stimulus dollars here?“

Renee Fry McKibbin noted that the burden of COVID-19 falls on front-line workers in health, caring industries, hospitality, tourism, arts and education, yet she said the budget focused on sectors "traditionally dominated by men”.

Climate change overlooked

Wood said the price of those blindspots would be a weaker recovery than otherwise, unemployment higher for longer than it could have been, and women’s economic disadvantage entrenched.

Labour market specialist Sue Richardson said relying on incentives such as instant asset write-offs and hiring subsidies was risky because the private sector might not respond in the way that had been hoped.

What direct spending there was seemed “intended largely to recreate the economy of the past, rather than invest in the economy of the future”.

Read more: Budget 2020: promising tax breaks, but relying on hope

“The economy of the future will, among other things, need to have much lower greenhouse gas emissions and much greater ability to cope with the unavoidable damage arising from climate change.”

How we handle the recovery will either set us on a path towards net-zero emissions or lock us into a fossil fuel system from which it will be hard to escape.

Saul Eslake gave the government “great credit for being willing, explicitly, to recalibrate its budget strategy” and run up what (for Australia) were large amounts of debt.

On average, a bare pass

But he said the measures chosen would be less effective in delivering jobs and recovery than others available including vouchers for spending in sectors hard-hit sectors and spending on social housing and childcare.

All but one of the 43 economists who responded to the survey also responded to the pre-budget survey which nominated spending on social housing, education and training and permanently boosting JobSeeker as the top budget priorities.

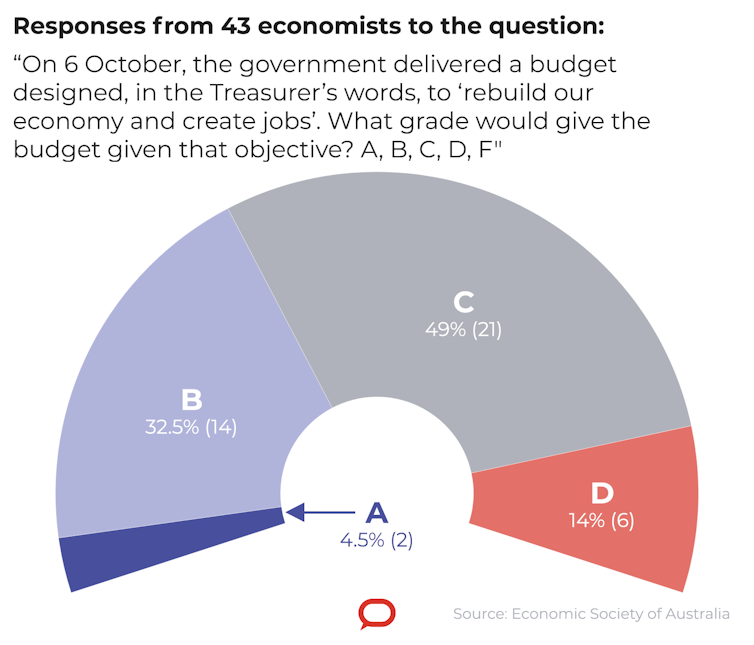

Assessing the budget, 16 of the 43 (37%) awarded it either an A or a B. Almost half (49%) awarded it a C, or “bare pass”. Six (14%) gave it a D.

Some of the economists who awarded a B said it was really a “B-minus”

One of them, Lata Gangadharan, said when it came to opportunities for women (those worst affected by the downturn) the budget “failed miserably” and would attract a D.

James Morley said he might have been “too easy of a marker” by awarding a B, but that it was “possible to lose the forest for the trees when only evaluating the budget on its specifics”.

‘B’ reflects the big picture, not the details

The big picture was that deficit-financed stimulus was needed and that the budget provided much more than might have been expected given the previous positions of the treasury and the Morrison government.

He said the forward guidance that put off “budget repair” until after the unemployment rate fell below 6% was welcome, even if one could ask why the threshold of 6% number had been chosen.

The more one looks at the details, the more one wants to significantly mark down the grade for budget. But I will still give it a “B” because the big picture is on the right track and I will just hope the Treasurer somehow becomes an “A” student in the future.

Rana Roy said he would have to grade the budget a C rather than an A or B, “more in sorrow than in anger”.

While he approved of the deficits and the tax cuts and the focus on infrastructure, he strongly suspected the measures would not be enough.

“For example, in an immediate sense it is likely that the negative impact of tapering and terminating JobKeeper will overpower the positive impact of the new wage subsidies for new hires.”

Read more: Top economists back boosts to JobSeeker and social housing over tax cuts in pre-budget poll

Two of those surveyed awarded the budget a B primarily because it had shown restraint. Tony Makin said too much spending would have pushed up the dollar and drawn resources away from the private sector. Geoffrey Kingston said it was important to avoid “maxing out the national credit card”.

Chris Edmond awarded it a C primarily because its assumptions relied on hope.

By simply assuming a widespread effective vaccine will be available next year and not otherwise thinking hard about how to beat the pandemic, the government is being very optimistic.

Others said it had ignored the one thing recommended by most economists, which was to invest in social housing to make housing affordable and create jobs.

A permanent increase JobSeeker would have given a million Australian confidence in the leadup to Christmas. Higher education, a major export earner with a direct impact on productivity, was being left to shrink.

John Quiggin said the budget pursued “cultural/ideological vendettas against perceived enemies like renewable energy and the university sector”.

But he said it was still worth a C. The government was right to budget for a large deficit, and deserved continuing credit for JobSeeker and JobKeeper.

Individual responses

![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.