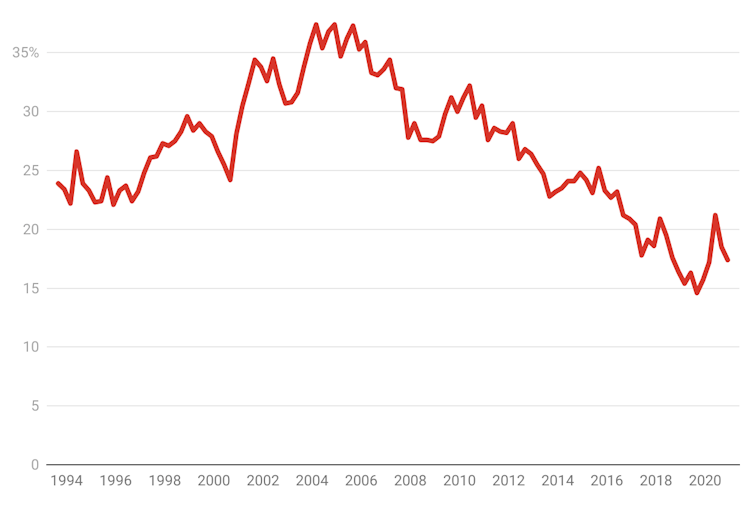

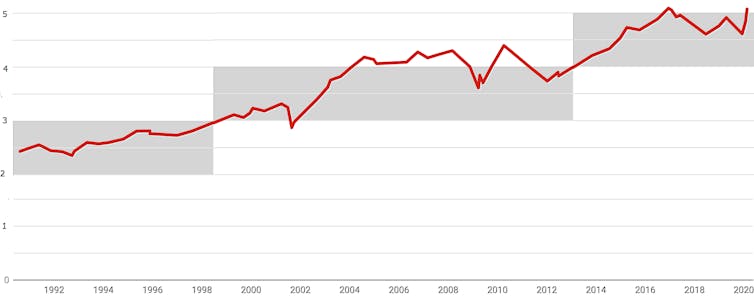

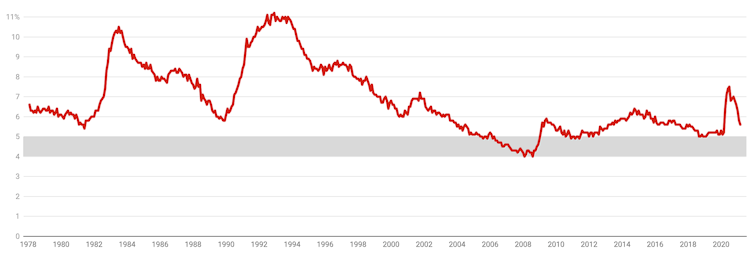

Australia’s top economists have overwhelmingly backed a decision by Treasurer Josh Frydenberg to reset the budget strategy so that it prioritises achieving an unemployment rate of between 4% and 5% over reducing debt.

Australia hasn’t had an unemployment rate below 5% since 2011.

It hasn’t had an unemployment rate below 4% since the early 1970s.

Unemployment rate, per cent

The new wording of the fiscal strategy required in the budget as part of the Charter of Budget Honesty will commit the government to quickly drive down unemployment until the unemployment rate is between 4% and 5%.

Only when the unemployment rate is sustainably within that band will the strategy switch to a focus on reducing government debt as a share of GDP.

Read more: Josh Frydenberg has the opportunity to transform Australia, permanently lowering unemployment

The existing wording, introduced in last year’s budget in response to the COVID crisis, only commits the government to drive down unemployment until the rate is “comfortably below 6%”.

Treasurer Frydenberg spelled out the new strategy in an address to the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry on Thursday saying both the treasury and the Reserve Bank now believed the so-called non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment was lower than 5%.

“In effect, both the bank and treasury’s best estimate is that the unemployment rate will now need to have a four in front of it,” he said.

Like it was under Menzies

The Reserve Bank was limited in its ability to cut interest rates further, meaning greater weight would have to be placed on the budget to bring unemployment down to between 4% and 5%.

The exact wording of the new strategy will be unveiled on budget night, May 11.

The increased ambition means the government plans to usher in an era of sustained low unemployment not seen since the prime ministerships of Robert Menzies, Harold Hold, John Gorton and William McMahon.

Backed by 6 in 10 leading economists

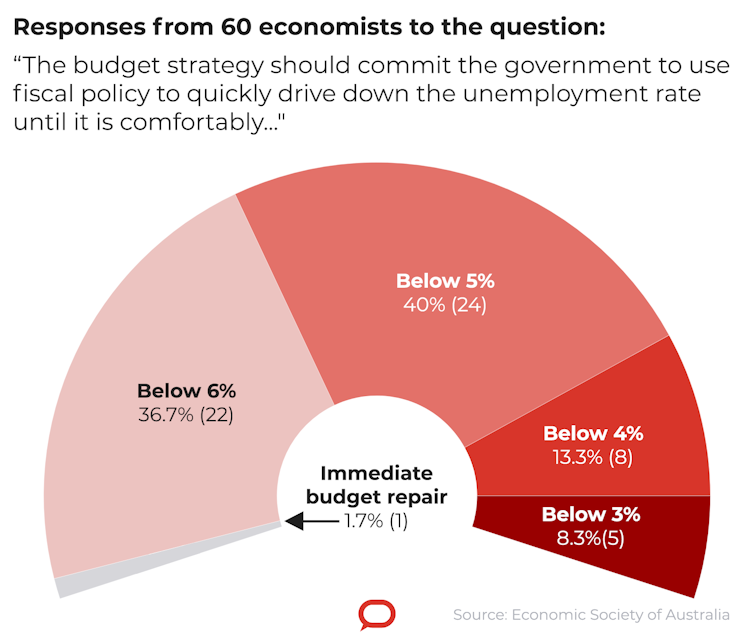

Of the 60 leading Australian economists surveyed by the Economic Society of Australia and The Conversation ahead of the announcement, more than 60% wanted the target strengthened to an unemployment rate below 5%.

Some 21% (13 of the 60 surveyed) want the target strengthened to an unemployment rate below 4%.

Five want the target strengthened to an unemployment rate below 3%.

Only one of the 60 top economists surveyed wanted an immediate tightening of the budget regardless of the unemployment rate.

Tony Makin, a former International Monetary Fund and treasury economist who was critical of Australia’s stimulus program during the global financial crisis says the present ultra-low interest rate settings are more than enough to drive unemployment as low as it can get without stoking runaway inflation.

He says the extra government debt that would be created by a push for even lower unemployment would put Australia’s credit rating at risk and push up interest rates and the Australian dollar, making Australian exports less competitive.

‘Unusual opportunity’

The economists chosen by the Economic Society to take part in the survey are recognised leaders in fields including microeconomics, macroeconomics, economic modelling and public policy.

Among them are former and current government advisers, former heads of government departments and agencies, and a former member of the Reserve Bank board.

Labour market specialist Sue Richardson said Australia faced an unusual opportunity to test how low unemployment can go before a tight labour market produces unacceptable stresses.

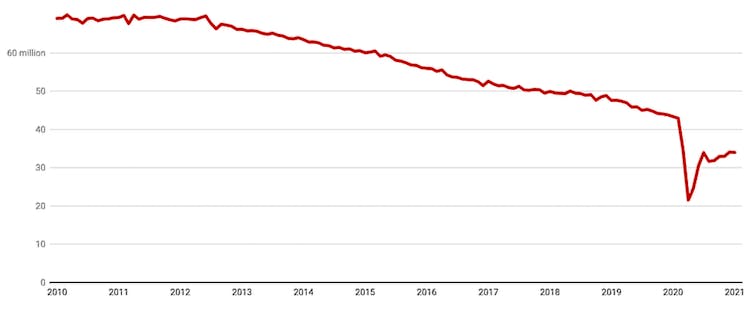

US unemployment got down to 3.5%

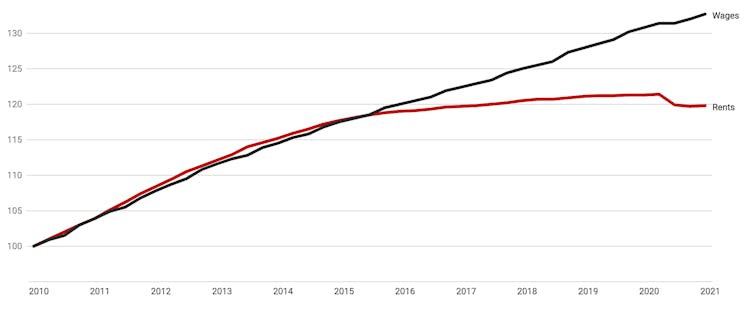

The combination of reduced temporary migration, very low inflation and inflation expectations and a relaxation in the focus on containing the size of government debt made this a rare moment.

Consultant Nicki Hutley said if the experience of the United States before COVID was any guide, Australia might be able to get its unemployment rate down to 3.5% without stoking accelerating inflation.

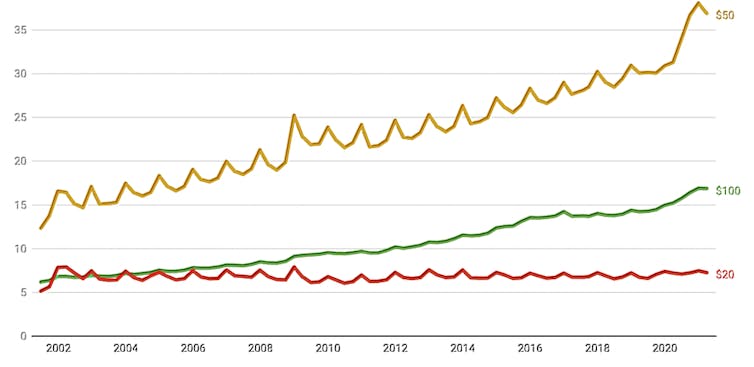

With interest rates at such low levels, investing in Australia’s economic future could not be a better decision.

Taking pressure off the Reserve Bank

Economist Saul Eslake said it wasn’t unreasonable for the treasurer to have proposed a threshold of an unemployment rate “comfortably below 6%” before beginning budget repair last year, given that at that time the conventional wisdom was that unemployment was headed to 10%.

But now both the Treasury and the Reserve Bank have made it clear unemployment can be forced lower without stoking inflation, “four point something” is realistic.

Inflation figures released on Wednesday showed one of the most reliable measures of inflation, known as the “trimed mean”, at an all-time low.

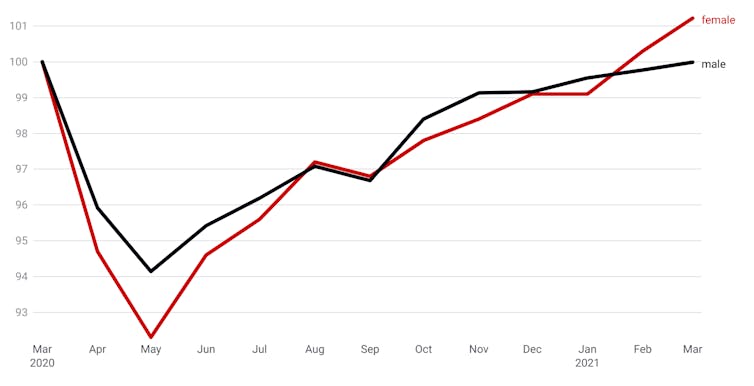

Read more: Jobs for men have barely grown since the COVID recession. What matters now is what we do about it

Another reason for the government to delay winding back debt was that it would give the Reserve Bank an opportunity to lift interest rates sooner, giving it greater ability to cut interest rates to fight downturns in the future.

A report released by the Parliamentary Budget Office on Wednesday said reducing the government’s debt-to-GDP ratio to pre-pandemic levels would take decades, “even under relatively optimistic scenarios”.

But it added that debt servicing costs should remain subdued as the existing debt was borrowed at historically low interest rates.

Macquarie University’s Geoffrey Kingston said it was the wrong time to be thinking about either an unemployment or a debt target. What mattered, this year more than most, was the composition of government spending.

This meant better supplies of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, more facilities for mass vaccinations and safer quarantine.

Peripheral programs such as subsidising airfares to holiday destinations at a time when it remained imprudent to encourage air travel were much less important — even if they helped fight unemployment.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.