We are about to find out whether we’ll lose a tax break worth up to $1,080 a year.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg says he hadn’t “made any final decision” on the A$7.8 billion per year low and middle income tax offset ahead of next month’s budget.

He also says it was never intended to be “a permanent feature of the tax system”, which is true enough.

He could have added that it is incredibly poorly designed, introduced for a purpose that no longer exists, extended for a purpose that didn’t make sense, and now can’t be abolished without giving people a “pay cut”.

The low and middle income tax offset (LMITO) was introduced by Scott Morrison in his final budget as treasurer before becoming prime minister in 2018.

Its peculiar design owes much to the government’s experience with Robodebt, and its ill-fated attempt to collect what it believed were overpaid Centrelink benefits.

A flawed tax break, designed in Robodebt’s shadow

Morrison was by then acutely aware of the anguish caused by Robodebt, officially called the online compliance intervention program – which many people forget he introduced in 2016 to ensure “welfare recipients accurately disclose assets and investments”.

Robodebt sent what looked like demands for repayment to Australians who often owed nothing, and ended up costing the government A$1.8 billion in settlements.

LMITO was born of a desire to flatten Australia’s income tax scale and avoid the mistakes of Robodebt.

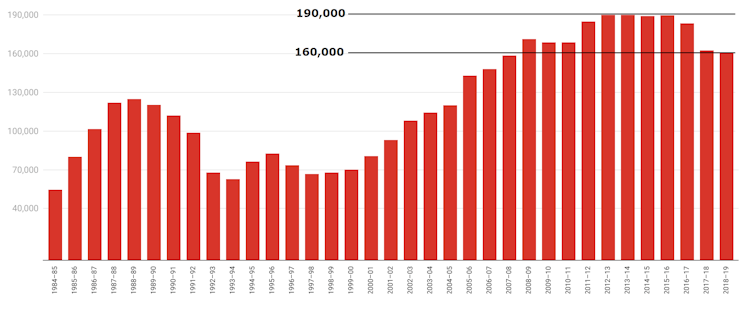

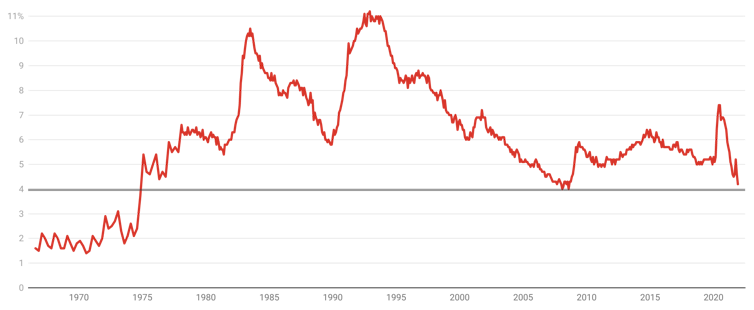

Australia has five tax rates counting the initial tax rate of zero, which applies to dollars earned up to $18,200. Anything earned above $18,200 up to a threshold gets taxed at 19%, anything beyond the next threshold gets taxed at 32.5%, anything beyond the next at 37%, and anything beyond $180,000 at 45%.

Morrison wanted to remove one of the thresholds, the one that introduced the 37% tax rate, leaving the scale with just three rates above zero: 19%, 32.5% and 45%.

The cost would be enormous, climbing to $24.6 billion per year. By then 44% of the benefit would go to the highest earning Australians on more than $180,000.

Part one of a three-part plan

So Morrison did it in stages. The first would provide “tax relief for middle and low income earners now”. It would be limited to taxpayers earning up to $125,333.

The second, in 2022-23, would push out two of the thresholds: 32.5% would come in at $45,000 instead of $37,000, and 37% would come in at $120,000 instead of $90,000. And the LMITO tax break would go. It wouldn’t be needed, because people getting it would get at least as much from stage two.

The third and final stage, in 2024-25, would flatten the tax scale.

But the problem with directing a benefit to what Morrison called “low and middle earners” was ensuring it went only to them.

What if one of them thought they would earn $100,000, and actually earned $150,000?

They’d have to be sent letters asking them to pay the money back, as with Robodebt.

So Morrison and the treasury decided recipients wouldn’t get the money until they had put in their tax returns, documenting what they made.

The offset would begin in July 2018, but the money wouldn’t hit the recipients’ bank accounts for more than a year, until the second half of 2019 – after their tax had been sorted.

Despite being called the low and middle income tax offset, very low earners would get nothing.

Those on less than $18,200 had no tax to refund. The rest would get up to $530 (later lifted to $1,080) – but only after they had done their tax. And the messy arrangement was only to last for a few years, until the second stage came in.

‘Not permanent’, but hard to stop

In 2020, as part of the government’s COVID response, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg brought forward stage two. At that point, the offset was no longer needed.

But, perhaps in order to claim “the greatest benefits will flow to those on lower incomes”, Frydenberg extended the offset for another year.

In 2021 he extended it for yet another year, this time as a “stimulus measure”, albeit an ineffective one. A stimulus measure that doesn’t hit bank accounts for more than a year is anything but immediate.

Frydenberg’s problem is that now he has given us both the offset and the stage two together, and done it for two years, actually ending the offset will quite rightly be seen as a tax increase or a “pay cut”, directed at low and middle earners. The timing is particularly tricky, with a federal election due weeks after this year’s budget.

Costing the best part of $8 billion per year, delivered when it is not needed, and destined to continue until someone can find a way to stop it, the offset is an awfully constructed annual bonus for all but the highest-earning Australians.

Like the instant asset write off for business, which keeps getting extended because otherwise businesses would complain, there’s a chance the LMITO will stay with us forever.

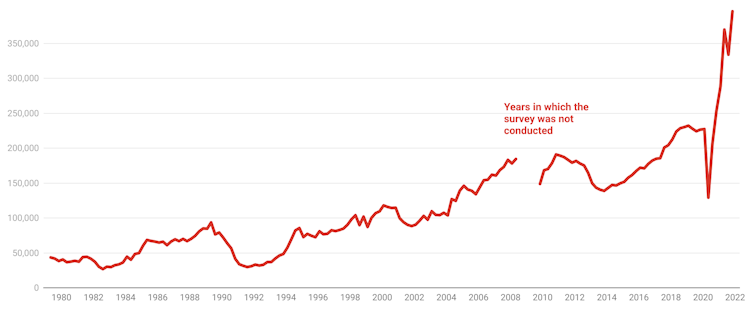

As ill-fitting as it is, there is an unexpected benefit. The Tax Office says we’ve been getting our returns in early.![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.