In 2007 Malcolm Turnbull turned off an industry’s life support without blinking.

The industry made light bulbs, of the traditional kind; so energy-inefficient they lost most of it as heat.

“A normal light bulb is too hot to hold — that heat is wasted, and globally represents millions of tonnes of carbon dioxide that needn’t have been emitted,” he explained.

From February 2009 it became illegal to import the traditional pear-shaped globes, while from November that year it became illegal to sell them.

It was a world-first, announced by Turnbull as environment minister and sanctioned by his prime minister John Howard.

The European Union followed, and then, some years later, China.

Globally, electric lighting generated emissions equal to 70% of those from cars. Australia’s switch cut emissions by an estimated 4 million tonnes per year.

Turnbull was able to do it because Australia no longer made light globes.

There was no domestic industry — and no jobs — to protect.

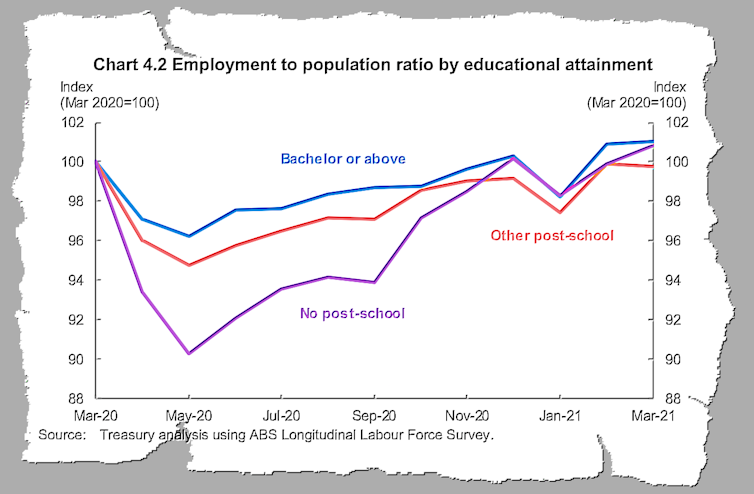

Australia stopped making cars in 2017. The thousands of workers who used to assemble cars in Australia no longer have those jobs.

Which means there’s no car industry to protect.

We have the opportunity to do to traditionally-powered cars what we did to incandescent light bulbs.

And the need. We’ve all but committed ourselves to net-zero emissions by 2050.

In a landmark report released last Tuesday, the International Energy Agency said the path to net-zero by 2050 was narrow and extremely challenging, requiring governments to “take action this year and every year after so that the goal does not slip out of reach”.

Many of the 400 or so milestones it set out are challenging for Australia, among them no new coal mines or mine expansions from this year, and the closure of almost all of Australia’s coal-fired power stations by the end of this decade.

But one of the milestones ought to be easy.

It’s no new sales of internal combustion cars by 2035.

The rest of the world is racing ahead

As a step along the way, the agency wants two-thirds of all new cars sold to be petrol-free by 2030. Australia, with no vehicle production industry to care about, ought to get there sooner.

Norway has promised no new petrol car sales by 2025; Denmark, the Netherlands, Ireland and Israel by 2030; and California and the United Kingdom by 2035, a target the UK has brought forward from 2040.

In addition, the European Union is imposing manufacturer-specific emissions targets, which will force each one to either sell a greater proportion of non-petrol vehicles or make the ones they do sell much more efficient.

Read more: Costly, toxic and slow to charge? Busting electric car myths

Manufacturers are getting in early. Honda says it will sell only electric and hybrid vehicles in Europe starting in 2022, three years earlier than previously planned. Volvo says 50% of its worldwide sales will be fully electric by 2025 and the rest hybrids.

Like the transitions to colour TV, automatic car windows, automatic transmissions and transistor radios, the shift will be one way. When production lines are retooled, there will be no turning back.

Moving quickly would do more than help Prime Minister Scott Morrison produce a credible roadmap to take to Glasgow climate talks in November.

It would enable us to avoid becoming a dumping ground for the dirtier, more polluting vehicles that can’t be sold elsewhere while the changeover is underway.

Switching soon would save us money

And it would save the government money. It has just committed to pay up to A$2 billion to keep Australia’s two remaining oil refineries open until 2027.

Without the payments, Ampol might have closed Lytton in Queensland (it was weighing up doing so) and Viva Energy refinery might have closed its loss-making refinery at Geelong.

While both have accepted the money, Ampol has unveiled plans to test the production of solar-powered hydrogen on its site at Lytton and Viva Energy is planning a solar farm on its site at Geelong.

Most of Australia’s petrol is imported, much of it from Singapore, meaning little would be lost if Australia’s refineries closed.

The Australian-produced fuel is dirtier than the imported fuel, something the Australian government promised to fix this month by paying Australia’s plants to make the ultra-low sulphur petrol the rest of the world switched to years ago.

If a ban on imports of petrol-powered cars wouldn’t much hurt Australia’s reluctant refiners, it might hurt petrol stations, but not much.

Australia’s service stations are in large measure retail convenience stores. They try to maximise “basket size”. Ampol plans to turn the petrol side of the business into a recharge and refuelling network for electric and hydrogen vehicles.

Mechanics would lose jobs

The much-larger industry at risk from a switch to electric vehicles is car maintenance. The Bureau of Statistics counts 352,200 automotive and engineering trades workers, almost all of them male and full time.

That a switch to low-maintenance electric vehicles would shrink their industry is unfortunate for them, but inevitable. Propping up their industry by delaying the transition would only encourage more young people into jobs with limited futures.

When Australia switched from valve to transistor-operated TV sets in the 1970s, an army of “television repair men” was thrown out of business, along with their vans and two-way radios.

Most of them stayed in the workforce doing things we needed.

To have kept using sets requiring maintenance just to have kept them in work would have been an insult to them and us.

And while Australia’s switch away from incandescent globes was problematic (many of us liked the yellowish glow we’d become used to) the switch to electric cars is looking positively joyous.

This week Crikey pointed to a video in which the Queensland MP Bob Katter gets his first taste of a Tesla as it accelerates from zero to 100 kilometres per hour in just over three seconds.

“Yeehaw!” he yells. “This is so exciting.”

Australians usually embrace the future. At times we’ve been ahead of it.

Read more: International Energy Agency warns against new fossil fuel projects. Guess what Australia did next?

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.