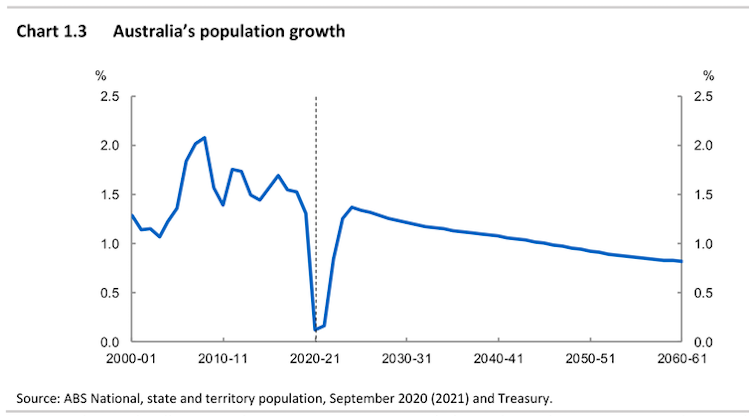

Australia will be smaller and older than previously expected in 40 years time after the first downward revision of official projections in an intergenerational report in 20 years.

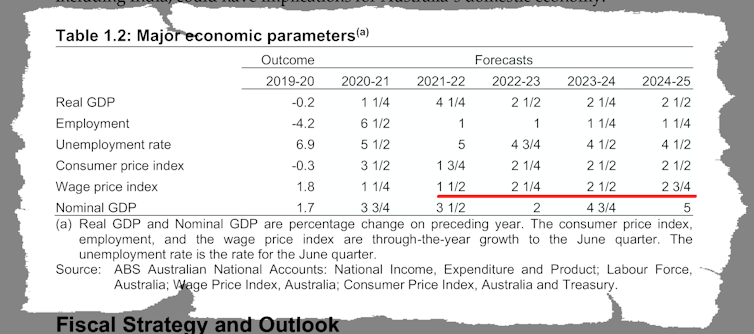

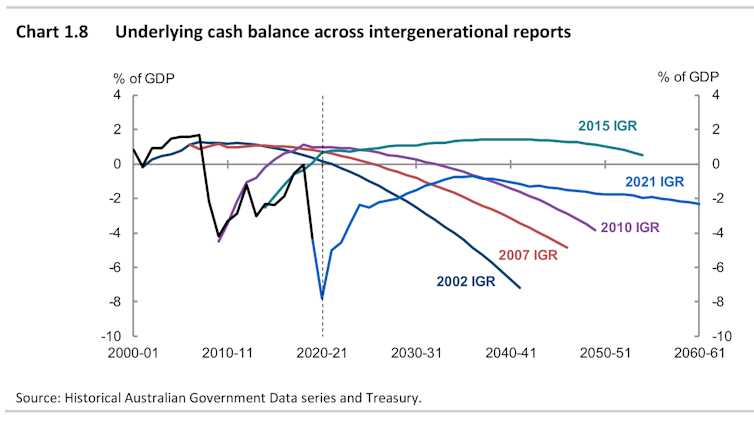

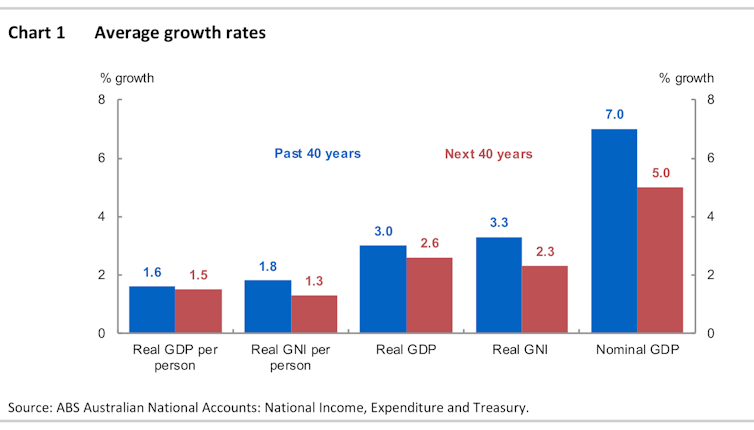

The much lower projections in Monday’s fifth five-yearly intergenerational report will mean indefinite budget deficits with no surplus projected for 40 years, only 2.7 Australians of traditional working age for each Australian over 65 (down from four) and average annual economic growth of 2.6%, down from 3%.

“Intergenerational reports always deliver sobering news, that is their role,” Treasurer Josh Frydenberg will say launching the report Monday morning. “The economic impact of COVID-19 is not short lived.”

The report says the pandemic has slowed both Australia’s birth rate and inflow of migrants.

The 2015 intergenerational report projected an Australian population of almost 40 million by 2054-55. The 2021 update projects 38.8 million by 2060-61.

As a result in 2060-61, about 23% of the population is projected to be over 65, up from 16% at present and 13% in 2002.

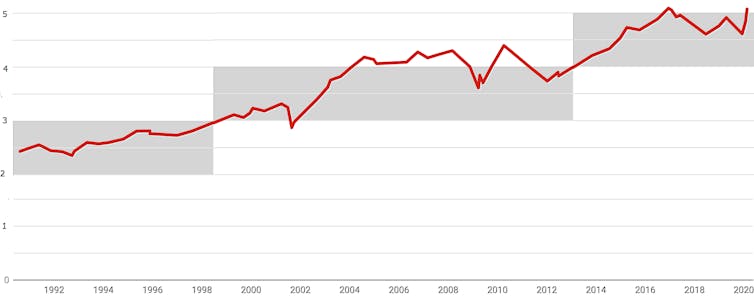

Although in the future increased superannuation would take pressure off the age pension, superannuation attracts favourable tax treatment which cuts government revenue.

The combined total of age pension spending and superannuation tax concessions was projected to grow from around 4.5% of gross domestic product to 5% by 2061.

Health, aged care spending to soar

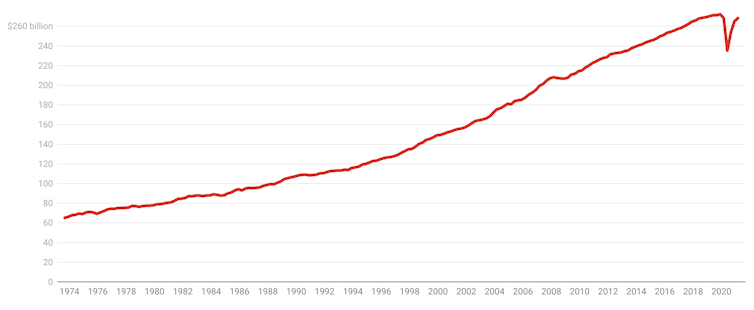

Real per person health spending is projected to more than double over the next 40 years, largely due to the costs of new health technologies.

By 2060-61 health is expected to be the largest component of government spending, eclipsing social security and accounting for 26% of all spending.

Aged care spending is projected to nearly double as a share of the economy, largely due to population ageing.

Read more: No Barnaby, 2050 isn't far away. The IGR deals with 2061

Mr Frydenberg will say that even in the face of these demands the government remains committed to its promise to limit the tax take to 23.9% of GDP. Tax receipts are not expected to reach this level until 2035-36.

“Growing the economy is Australia’s pathway to budget repair, not austerity or higher taxes. This is why we remain committed to our tax to GDP cap, ensuring our COVID support is temporary and persuing productivity-enhancing reforms.”

Net debt is projected to peak at 40.9% of GDP in 2024-25, before falling to 28.2% in 2044-45 and then climbing again to 34.4% by 2060-61.

While Australia’s population will be smaller and older, and debt levels higher as a result of the pandemic, had the government not spent at unprecedented levels to support the economy a generation of Australians might have been condemned to long term unemployment, seriously damaging the budget longer-term.

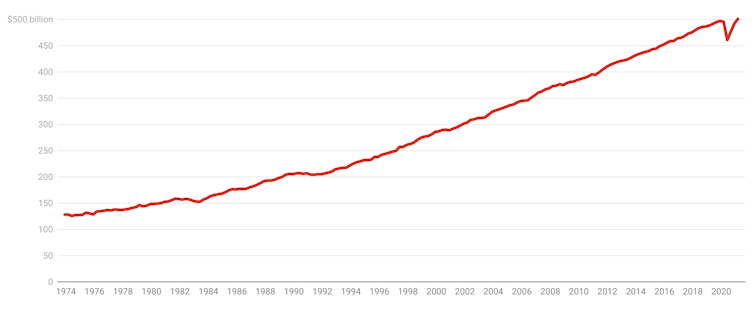

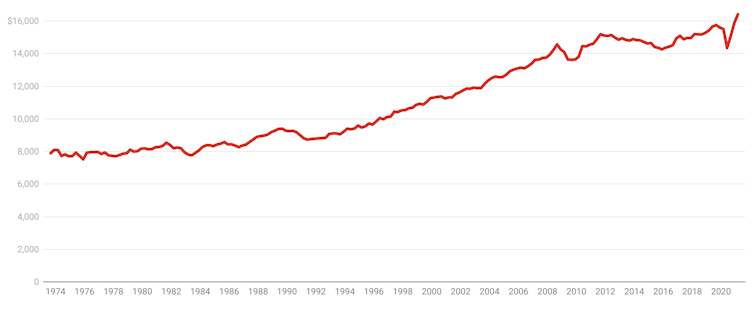

Other projections have real GDP per person a measure of living standards, growing at an annual average of 1.5%, down from an earlier-projected 1.6%

The result will still be a near-doubling of real GDP per person, from $76,700 in today’s dollars to $140,900 in today’s dollars in 2060-61.

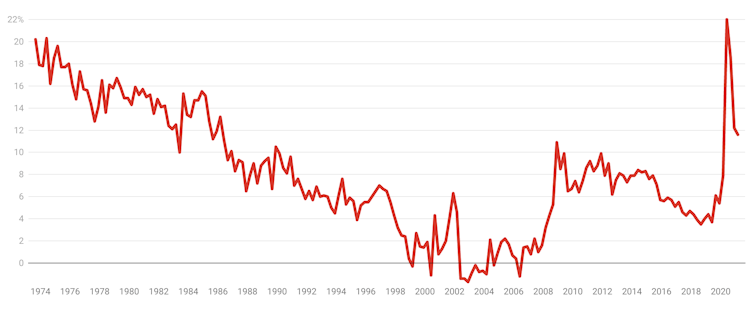

Behind that projection lies an assumed lift in annual labour productivity growth to 1.5%. In the decades before the pandemic, annual productivity growth had been averaging 1.2% and had slumped to 0.4% in the year leading up to the pandemic?

Read more: Why productivity growth stalled in 2005 (and isn't about to improve)

The lift in productivity assisted by government policies that will help individuals and businesses “take advantage of new innovations and technologies” is expected to take ten years.

Not included in the extracts from Monday’s report released by the treasurer late Sunday are the closely-watched projections for net overseas migration and for spending on the national disability insurance scheme.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.