The government’s new retirement incomes review will need to work quickly.

On Friday Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said he expected a final report by June, just seven months after the issues paper he wants it to deliver by November.

The deadline is tight for a reason. In recommending the inquiry in its report on the (in)effeciency of Australia’s superannuation system this year, the Productivity Commission said it should be completed “in advance of any increase in the superannuation guarantee rate”.

In other words, in advance of the next leglislated increase in compulsory superannuation contributions, which is on July 1, 2021.

Read more: Government retirement incomes inquiry puts superannuation in the frame

The next increase (actually, the next five increases) will hurt.

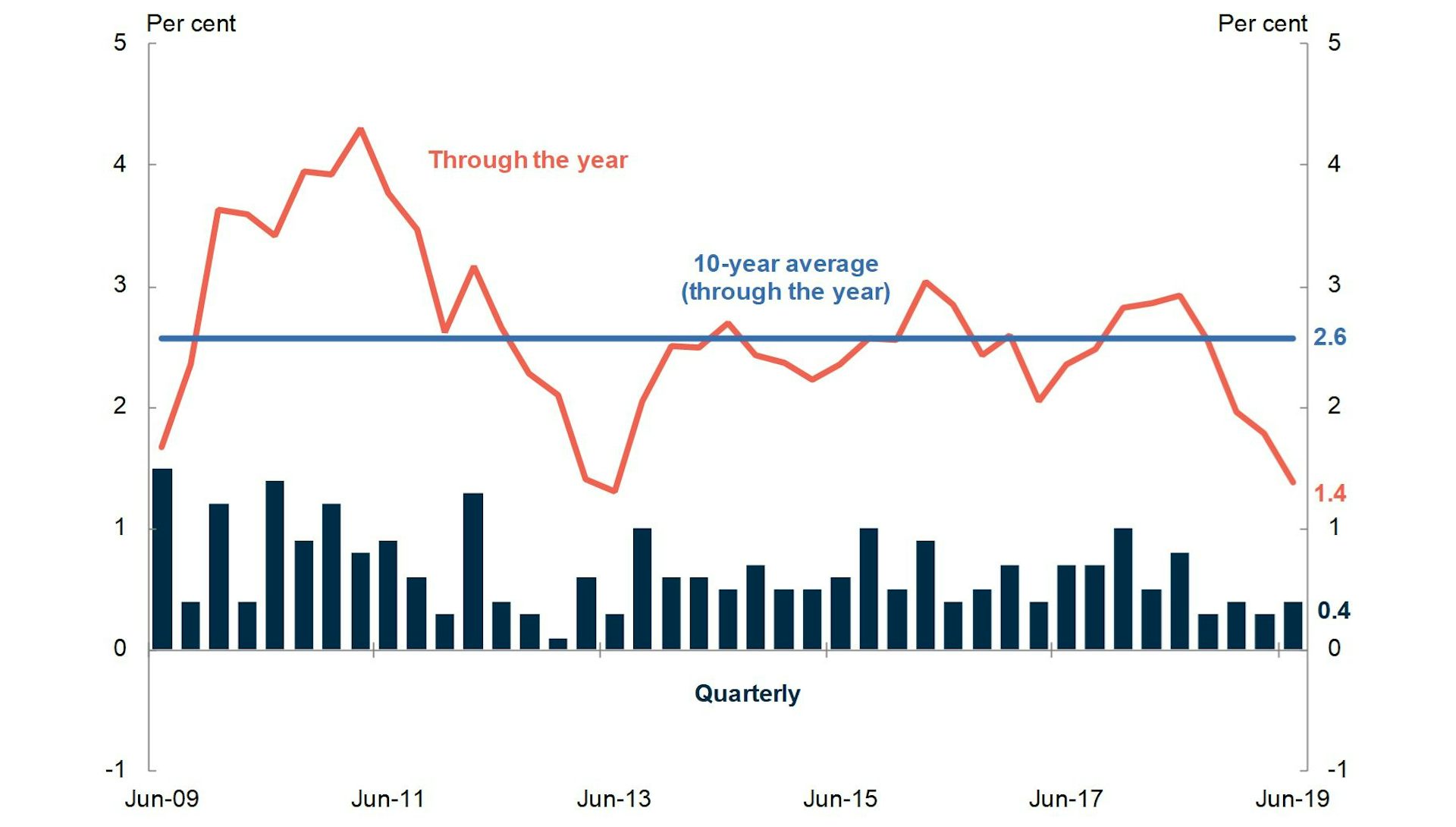

The last two, on July 1 2013 and July 1 2014, took place when wage growth was stronger. In 2013 wages growth was 3% per year.

And they were small – an extra 0.25 per cent of salary each.

The next five, to be imposed annually from July 1 2021, are twice the size: 0.5% of salary each.

If taken out of wage growth, they’ve the potential to cut it from its present usually low 2.3% per annum to something with a “1” in front of it, pushing it below the rate of inflation, for five consecutive years.

If we were going to do that (even if we thought the economy and wage growth could afford it) it would be a good idea to have a good reason why. After all, compulsory superannuation is the compulsory locking away of income that could otherwise be spent or used to pay down debt or saved through another vehicle, regardless of the wishes of the person whose income it is.

Question 1. What’s it for?

Fortunately, the new inquiry doesn’t need to do much work on this one.

For most of its life compulsory super hasn’t had an agreed purpose. At times it has been justified as a means of restraining wage growth, at times as means of restraining government spending on the pension, at times as means of boosting national savings.

In 2014, more than 20 years after compulsory super began, the Murray Financial System Review asked the government to set a clear objective for it, and two years later the government came up with one, enshrined in a bill entitled the Superannuation (Objective) Bill 2016.

The bill lapsed, but the objective at its centre lives on as the best description we’ve come up with yet of what compulsory super is for:

to provide income in retirement to substitute or supplement the age pension

Which raises the question of how much we need. For compulsory super, the answer is probably none. People who want more than the pension and their other savings can save more through voluntary super. People who don’t want more (or can’t afford to save more) shouldn’t.

Question 2. How much do people need?

Assuming for the moment that how much people need in retirement is relevant for determining how much compulsory super they need, the inquiry will need to examine what people need to live on in retirement.

The “standards” prepared by the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia are loose. The more generous of the two allows for overseas travel every two or so years, A$163 per couple per fortnight on dining out, $81 on alcohol “or equivalent spent with charity or church”.

Read more: Why we should worry less about retirement - and leave super at 9.5%

It isn’t a reasonable guide to how much people need to live on, and certainly isn’t a reasonable guide for how much the government should intervene to make sure they have to live on. They are standards it doesn’t intervene to support while people are working.

And there’s something else. Super isn’t what will fund it. Most retirement living is funded outside of super, either through the age pension, private savings, or the family home (which saves on rent). Most 65 year olds have more saved outside of super than in it, and a lot more than that saved in the family home.

It’s a slight of hand to say that retirees need a certain proportion of their final wage to live on and then to say that that’s how much super should provide.

Question 3: Does it come out of wages?

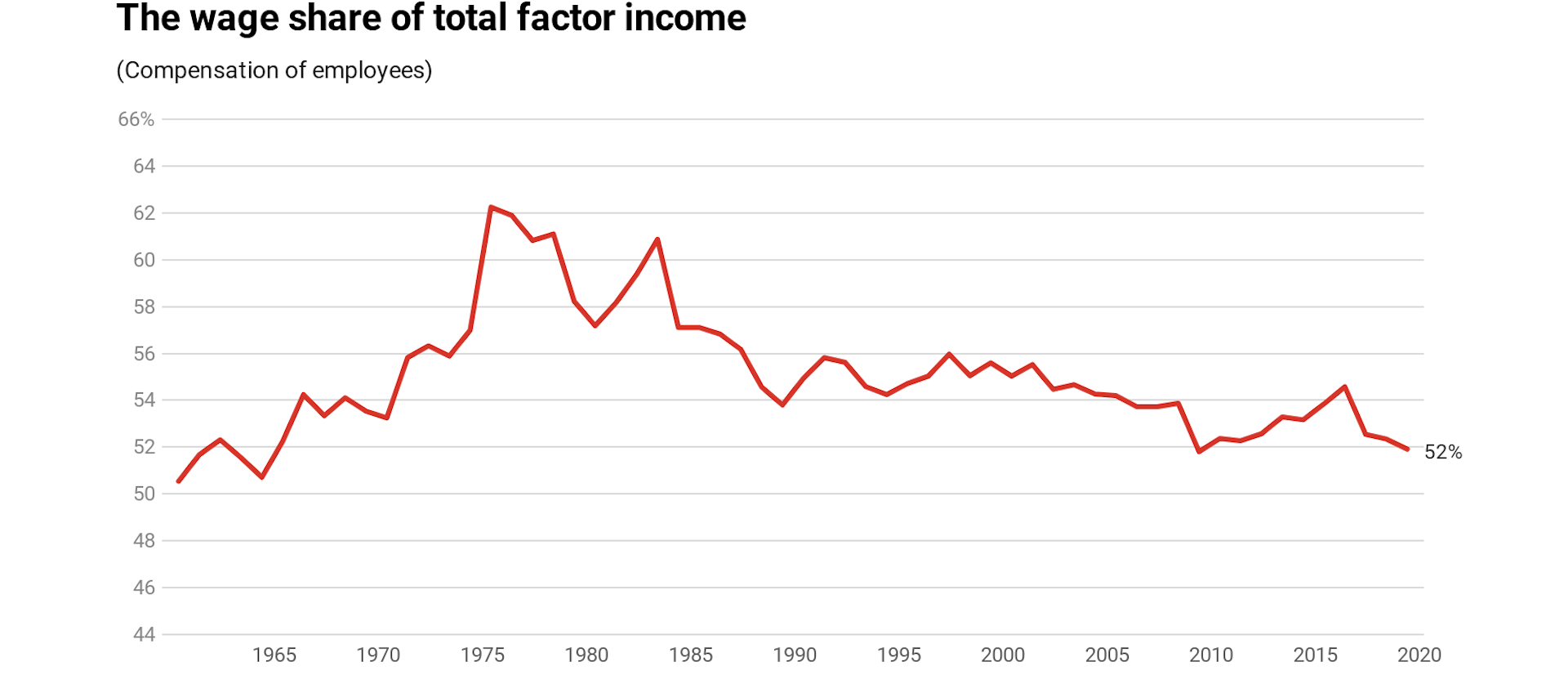

The best guess is that, although paid by employers in addition to wages, compulsory super comes out of what would otherwise have been their wage bill.

Treasury puts it this way:

Though compulsory superannuation guarantee contributions are paid by employers, wage setting generally takes into account all labour costs. As such, it is widely accepted that employees bear the cost of higher superannuation guarantees in the form of lower take home pay.

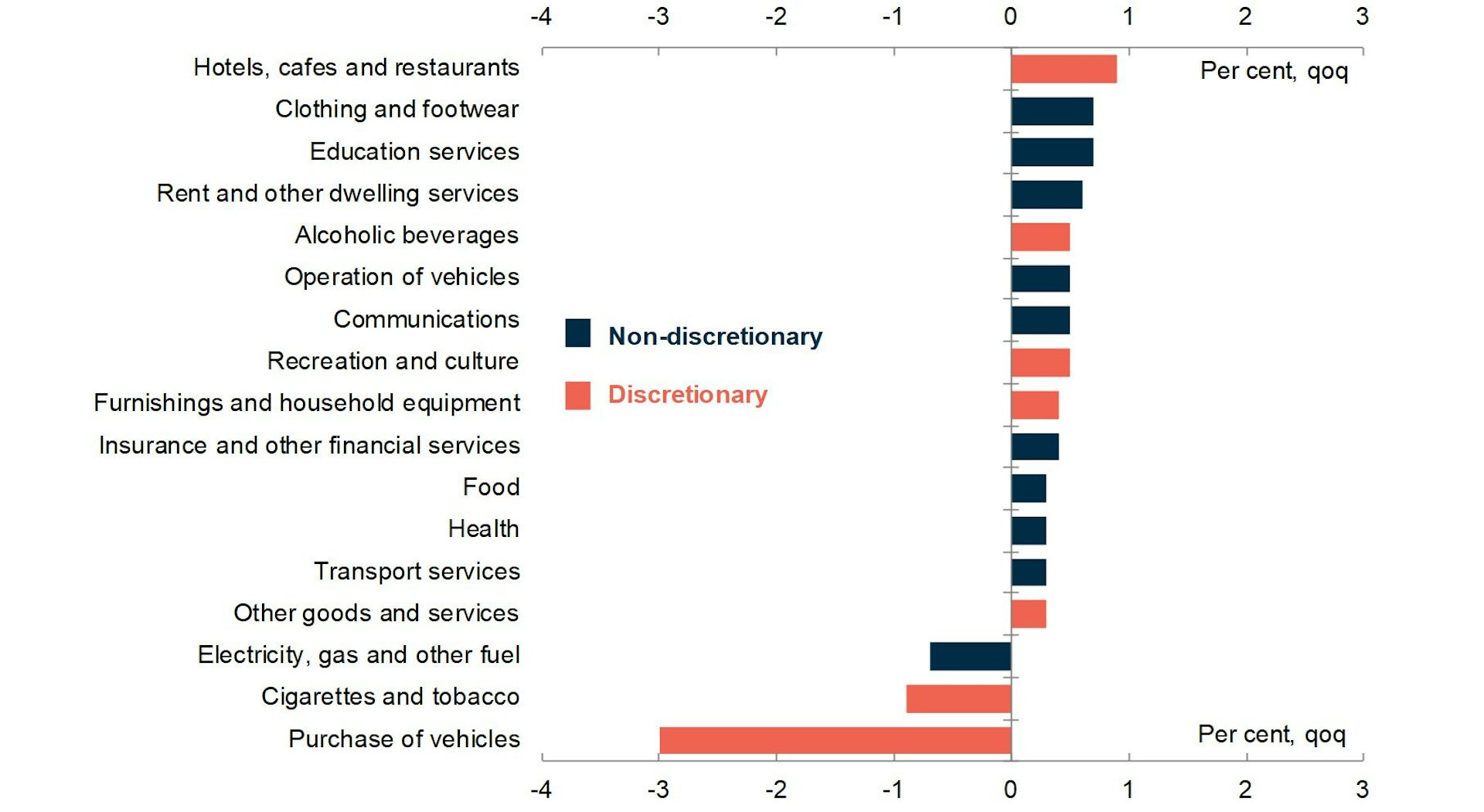

The inquiry will probably make its own determination. If it finds that extra contributions do indeed come out of what would have been pay rises, it will have to consider the tradeoff between lower pay rises (and they are already very low) and the compulsory provision of more superannuation in retirement.

Question 4: Does it boost private saving?

It’d be tempting to think that the compulsory nature of compulsory superannuation meant that each extra dollar funnelled into it increased retirement savings by an extra dollar. But it doesn’t, in part because wealthy Australians who are already saving a lot have the option of offsetting it by saving less in other ways.

For them, the increase in saving isn’t compulsory.

For financially stretched Australians unable to afford to save (or for Australians at times in times life when they can’t afford to save) the compulsion is real, and unwelcome.

The inquiry will have to make its own assessment, updating Reserve Bank research which found in 2007 that each extra dollar in compulsory accounts added between 70 and 90 cents to household wealth.

Question 5: Does it boost national saving?

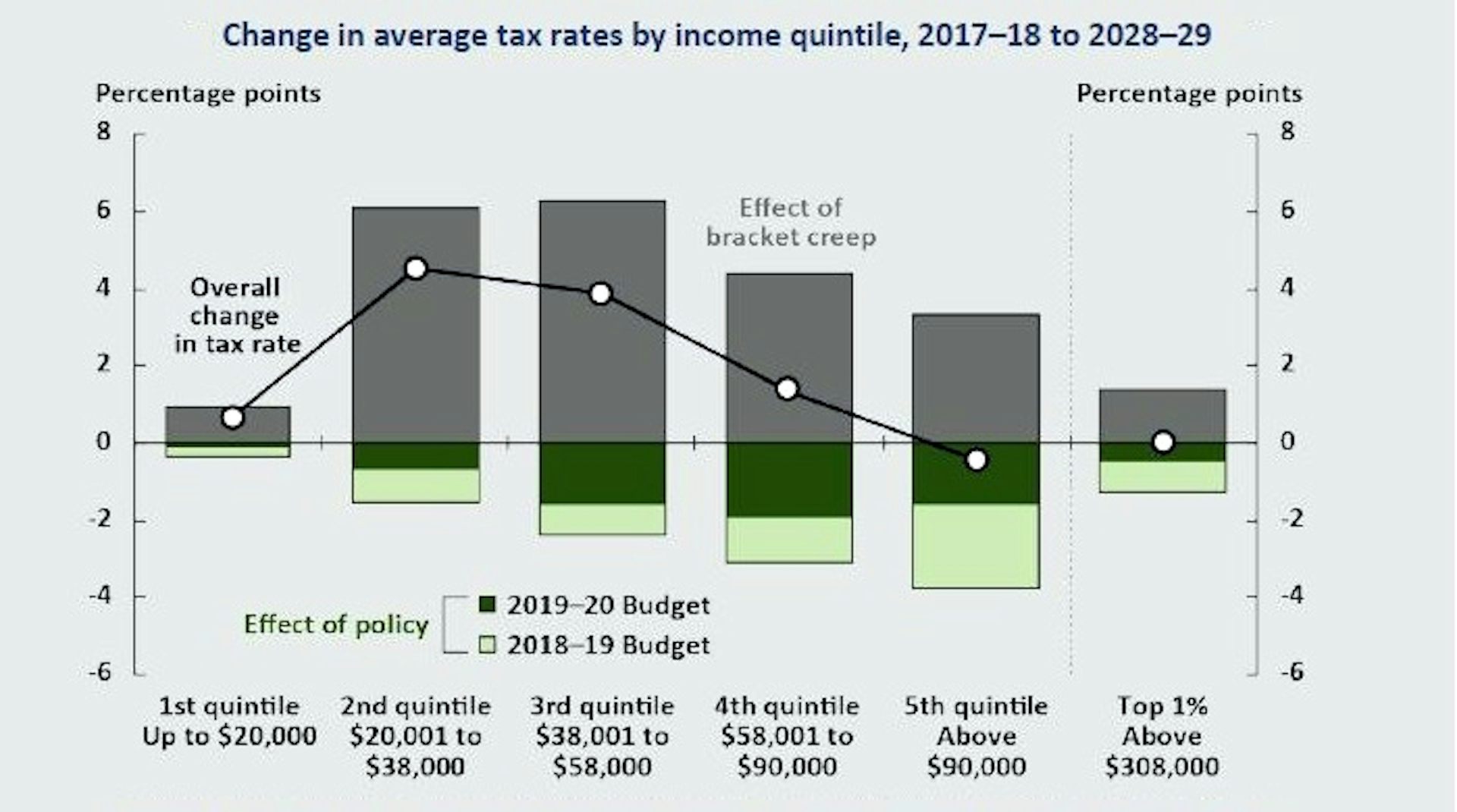

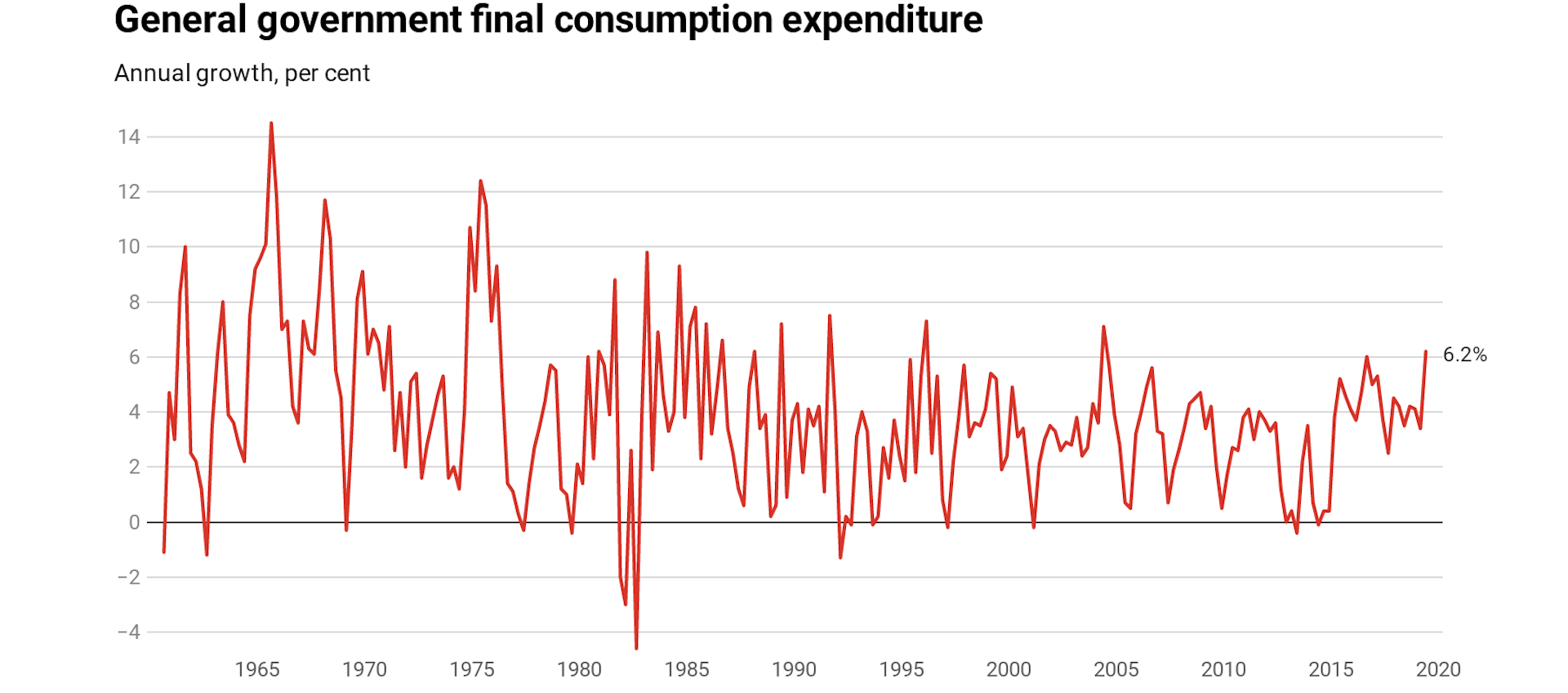

Boosting private saving (at the expense of people who are unable to escape) is one thing. Boosting national savings (private and government) is another. The tax concessions the government hands out to support superannuation are expensive. The concession on contributions alone is set to cost $19 billion this year and $23 billion in 2022-23, notwithstanding some tightening up. It predominately benefits high earners, the kind of people who don’t need assistance to save.

Read more: Myth busted. Boosting super would cost the budget more than it saved on age pensions

On balance it is likely that the system does little for national savings, cutting government savings by as much as it boosts private savings. But because the question hasn’t been asked, not since the Fitzgerald report on national saving in 1993 shortly after compulsory super was introduced, we don’t know.

It’ll be up to the inquiry to bring us up to date.![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.