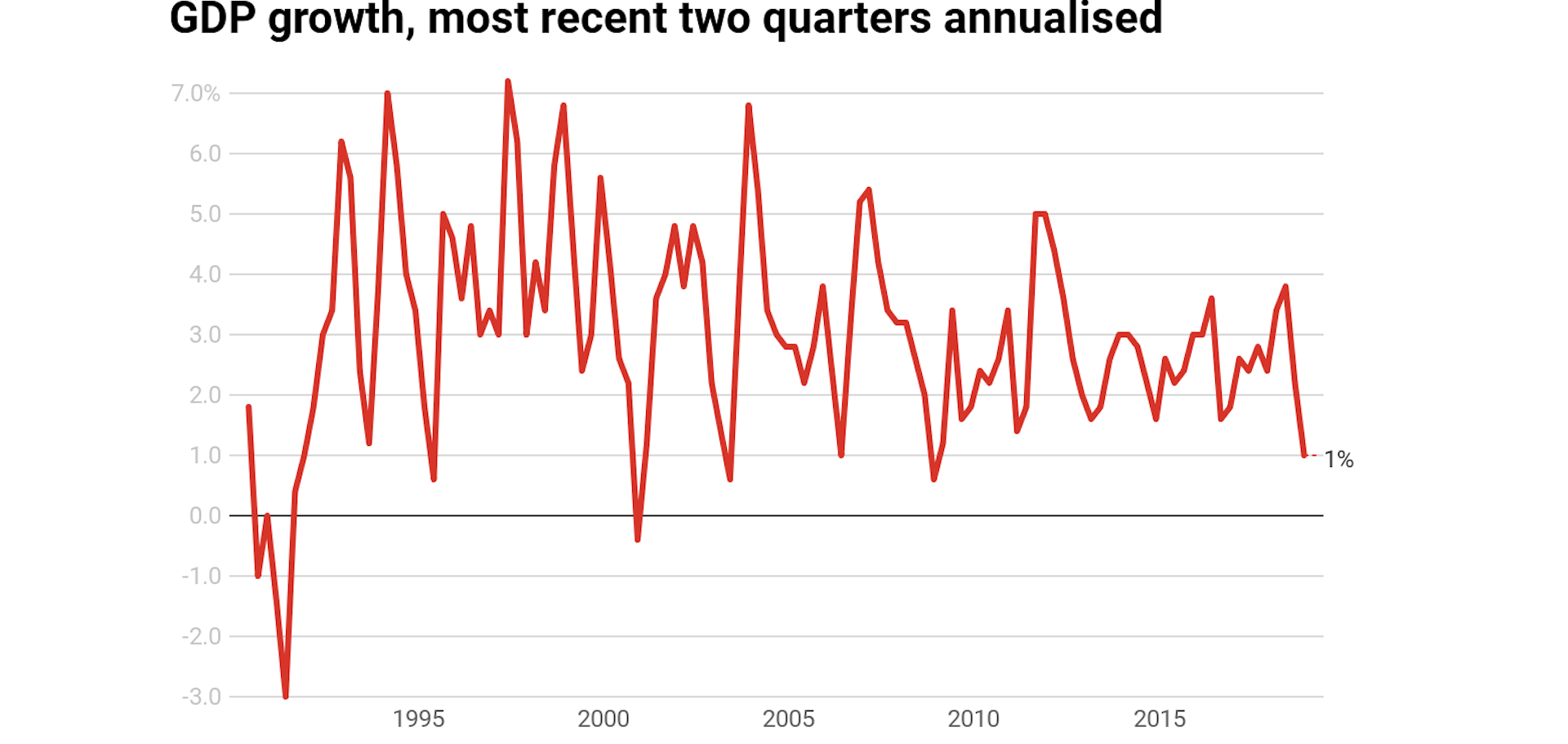

During the election we were promised jobs and growth. But in 2019-20 The Conversation’s forecasting panel is predicting an economic growth rate as weak as any since the financial crisis, as well as dismal consumer spending, no improvement in unemployment or wage growth, and an increased chance of recession.

As in January, The Conversation has assembled a forecasting panel of 20 leading economists from 12 universities across six states. Among them are macroeconomists, economic modellers, former Treasury, IMF, OECD and Reserve Bank officials, a former government minister and a former member of the Reserve Bank board.

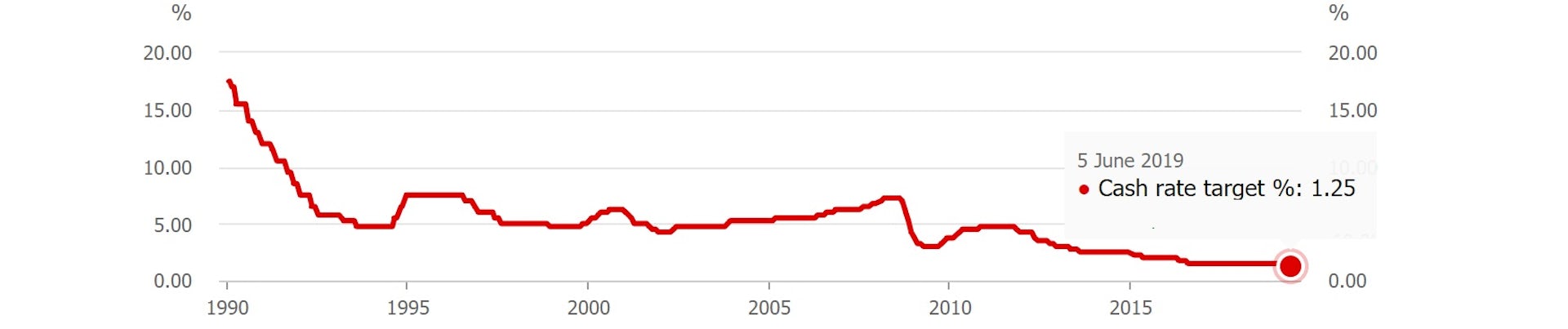

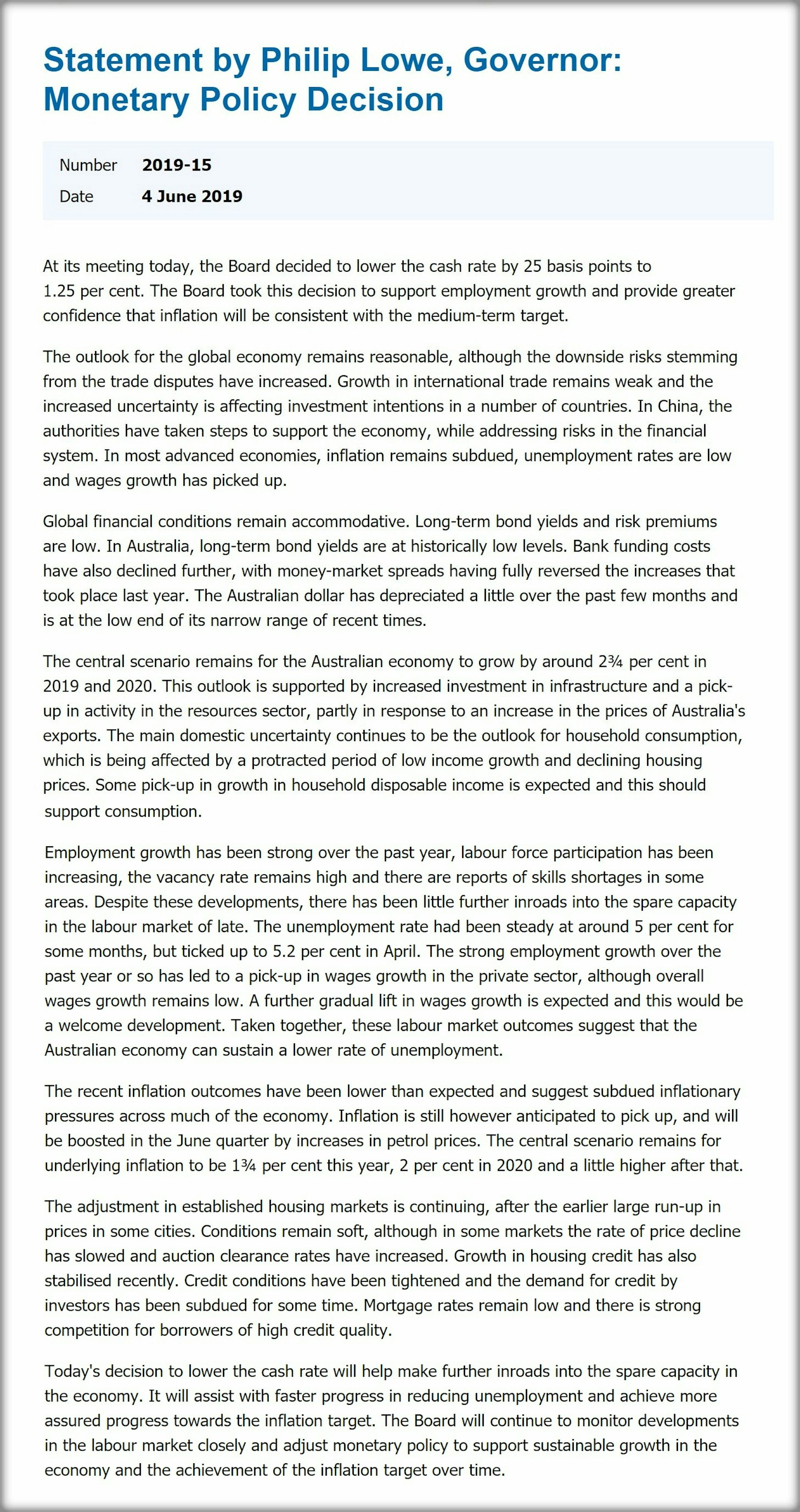

Whereas in January only three members of the 20-person panel expected the Reserve Bank to cut interest rates, and most expected an economic growth rate approaching 3% (which is the Treasury’s estimate of the best that can be achieved on a sustained basis), this time all but two expect the bank to cut again, and most expect a growth rate closer to 2% – one of the most anaemic since the financial crisis.

On the upside, the panel expects iron ore prices to stay higher for longer than did the budget, it expects home prices to stabilise, and it is predicting the lowest government bond rate on record, making it cheaper than ever before for the government to borrow and spend its way out of trouble.

The panel predicts a surplus in name only in 2019-20, and overwhelmingly believes the government should be prepared to abandon it if it has to in order to keep the economy growing.

Economic growth

The panel’s average forecast for year-on-year growth is 2.1%. Year-on-year growth is the measure used in the budget. It compares economic activity throughout all of one financial year with activity throughout all of the previous financial year. The budget forecast for 2019-20 is 2.75%.

Respected forecasters including former Reserve Bank board member Warwick McKibbin and former OECD director Adrian Blundell-Wignall expect much lower growth than 2.1%. McKibbin expects 1.8%; Blundell-Wignall expects 1.5%. Only three of the panel’s 20 forecasts are close to Treasury’s. The rest are lower.

Some panellists submitted forecasts for Chinese economic growth under sufferance. They made it clear they were forecasting “official” growth, not actual growth which they think is much lower. Even so, most expect official growth to slow as the trade war between the United States and China intensifies. Nigel Stapledon says unless it is reined in (and he thinks it will be) it could bring on recessions.

Other panellists including Rebecca Cassells say the impact of US tariffs on Chinese goods has so far been positive for Australia. China has responded by investing in infrastructure projects that need Australian iron ore and coal. This, together with reduced competition from other suppliers of iron ore after the collapse of a tailings dam and mine closures in Brazil, has lifted the price and volume of Australian exports to levels not seen for some time.

The panel expects robust United States growth of 2.6% in 2019, although many members are concerned about the year that will follow. The only panellist to forecast low US growth in this year (1%) is Blundell-Wignall, who until last year analysed world economies in his role as special advisor to the OECD secretary general.

Living standards

Jobs growth will disappoint both the Treasury, which has forecast unemployment of 5% by the end of the financial year, and Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe, who has adopted a target of “4 point something”.

All but three of the 20-person panel expect the rate to stay above 5%. The average forecast is 5.3%, which is close to the present 5.2%.

Stapledon says Australia’s recent strong employment growth has been “out of kilter” with slower GDP growth and the winding down of housing construction, meaning jobs growth is set to slow down, pushing up unemployment.

Brendan Coates says underemployment is also climbing as more people work fewer hours than they would like, making it harder for them to push for wage rises. Rebecca Cassells points out that full-time employment has grown almost twice as fast among women than men, which, given the low rates of pay in the industries that traditionally employ women, is likely to further depress average wages.

The headline measure of living standards, GDP per capita, has been falling, but a better measure, real net disposable income per capita, which takes better account of buying power, has been continuing to climb. The panel expected to climb a further 1% over the year to June 2020, after climbing 1.3% in the year to March.

Nominal GDP, which takes full account of mining revenue and drives company profits and the budget revenue, has grown 5% over the past year and is expected to grow 3% in the year ahead.

The risk of recession

The panel regards a recession as more likely than it did in January, assigning a 29% probability to a conventionally defined recession in the next two years, up from 25%.

Economic modeller Janine Dixon says the bulk of Australia’s recent economic growth has come from higher commodity prices via exports.

She says without them, Australia would be reliant on weak wage and consumption growth, although she believes high population growth will be enough to ensure economic activity doesn’t shrink for two consecutive quarters which would be the conventional definition of a recession.

Former Treasury and ANZ Bank economist Warren Hogan says with consumers tightening their belts, an external shock could easily knock Australia into a recession.

Julie Toth, an economist at the Australian Industry Group who has also worked for the Productivity Commission, says with growth already low, it won’t take much to turn it negative.

Debt theorist Steve Keen, who assigns a 95% probability a recession (as he did in January) says Australia escaped that fate during the global financial crisis in part by boosting grants to first home buyers, which made Australian households among the most indebted in the world and “put off the day of reckoning” when those debts would be unwound.

Through a mix of good luck and good management, Australia has avoided a recession during three global downturns since the early 1990s: the 1997 Asian economic crisis, the early 2000s dotcom collapse, and the 2007-09 global financial crisis. If it succeeds again it will enter its fourth decade recession-free in this term of government in mid-2021.

Wages and prices

The panel expects continued historically wage growth of only 2.2% in 2019-20, slightly weaker than the latest reading of 2.3% and well short of the budget forecast of 2.75%. If that average forecast is right, it will be the seventh consecutive year in which wage growth has fallen short of the budget forecast.

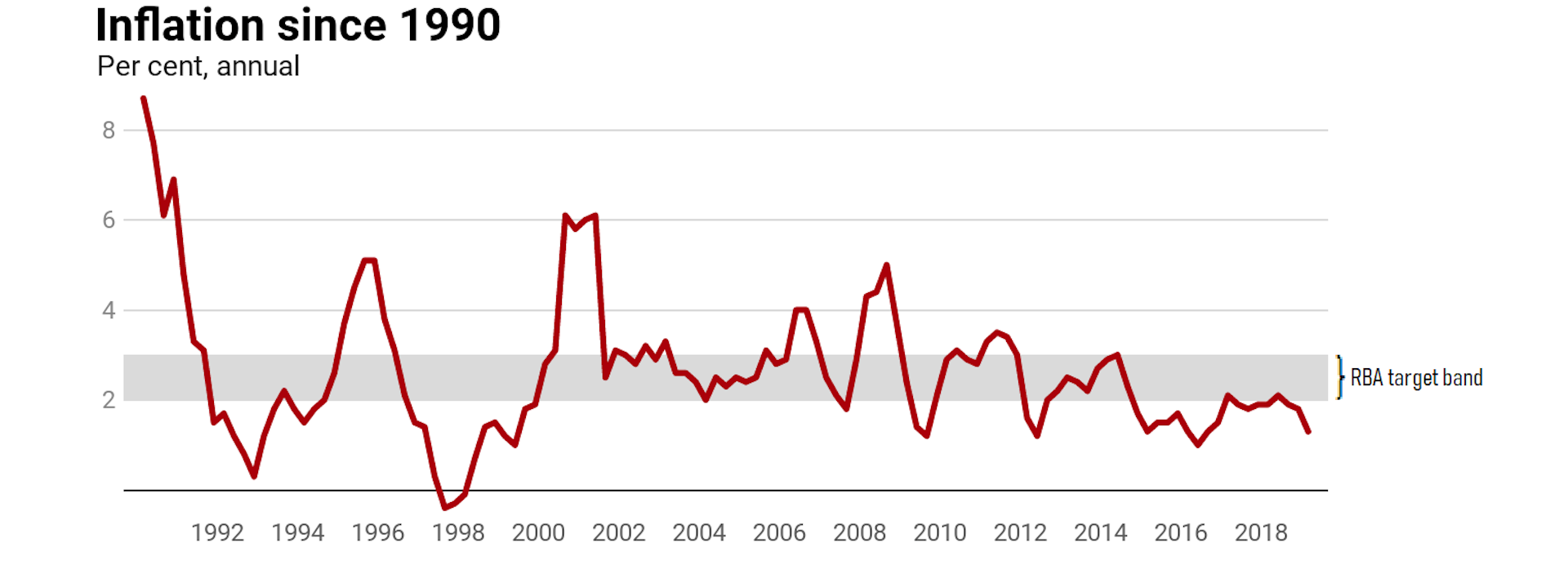

The good news (for wage earners) is that even that unusually low rate of wage growth would be well above the rate of inflation, which is expected to be only 1.5%, or 1.4% on the so-called “underlying” basis watched closely by the Reserve Bank.

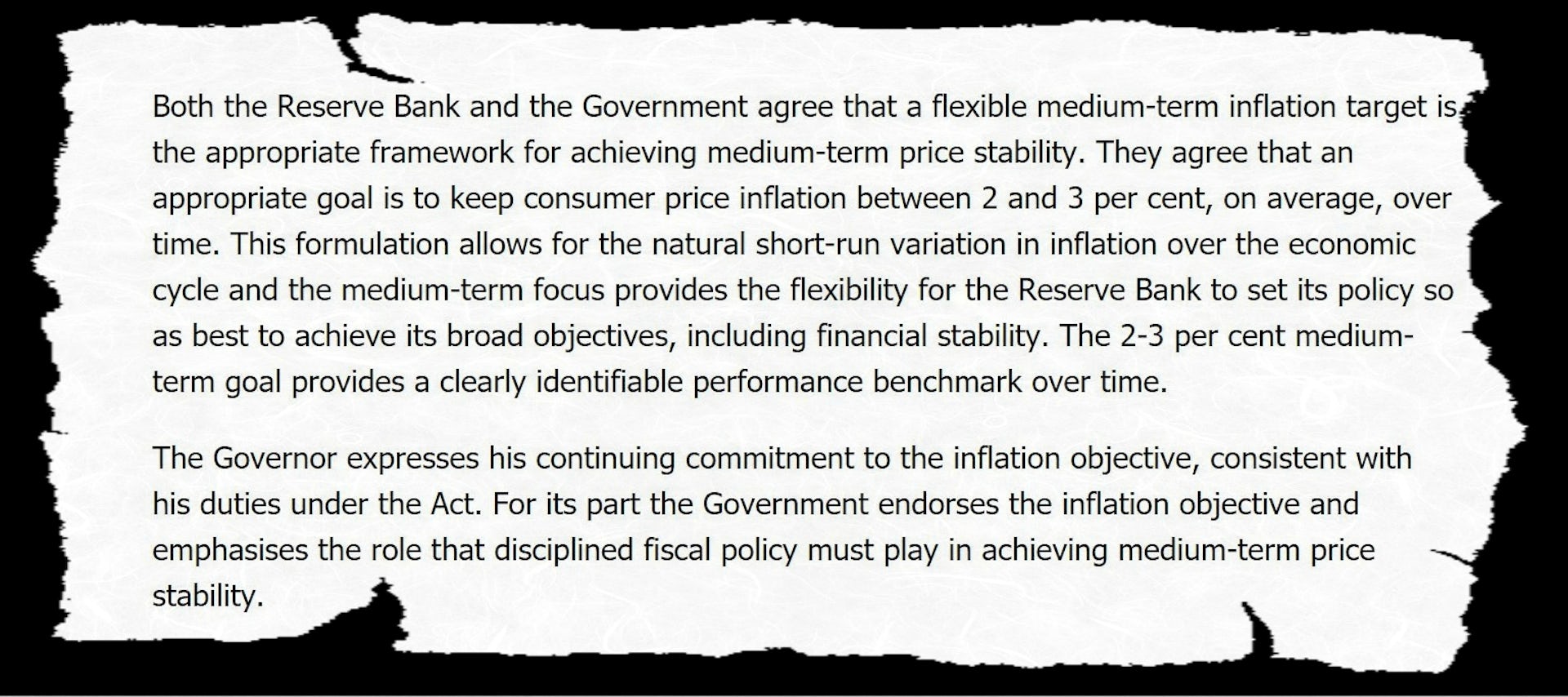

The bad news for the Reserve Bank is that it will put inflation well outside the bank’s target band of 2-3% for the fifth consecutive year, raising questions about whether there is any point to the band.

Mark Crosby, Warren Hogan and Adrian Blundell-Wignall suggest broadening the target band to 1-3%. Tony Makin and Nigel Stapledon suggest cutting it to 1-2%.

Richard Holden and Warwick McKibbin suggest ditching it altogether and replacing it with a target for nominal GDP growth. McKibbin suggests a nominal GDP target of 6%, which given the present forecast for weaker nominal GDP growth would mean interest rate cuts. In better times it would mean rate rises.

Chris Edmond and Craig Emerson defend the 2-3% inflation target saying that what is really concerning is the bank’s preparedness to stay beneath the target band for extended periods.

Home prices

The panel expects only modest falls in Sydney and Melbourne house prices of 2-3% in each city after falls of 10% over the past year. It is more optimistic on home building than is the Treasury, expecting housing investment to fall by 4.9% rather than the budget forecast of 7%.

Business

None of the panellists expects household spending to grow by the 2.75% forecast in the budget. On average, the panel expects spending growth of just 1.9% in 2019-20, which is little better than the present 1.8% and only few points above population growth.

Janine Dixon blames continuing weak growth in wages and incomes. Nigel Stapledon says much of it flows from the weaker housing market. Household furnishings drive household spending growth. Household spending drives GDP growth, accounting for more than half of it.

In better news, the panel expects mining investment to rebound after sliding for most of the last five years. Its forecasts of growth in mining investment of 4.4%, and growth in non-mining investment of 4%, are in line with budget forecasts.

Interest rates and the budget

Perhaps surprisingly given its forecasts for weak employment growth, weak economic growth and weak inflation, the panel’s average forecast for interest rates is for just one more cut, perhaps as soon as July 2, but some time in the second half of the year.

Only five panellists expect a followup cut in the first half of next year, but among them are Craig Emerson, Richard Holden and Steve Keen, who were the only three to correctly) forecast in January that there would be a rate cut at all this year.

Holden expects two further rate cuts in the second half of this year, taking the Reserve Bank cash rate to 0.75%, and then a further two in the first half of next year, taking it to just 0.25%. Keen expects one further cut on the second half of this year and another two in the first half of next year, taking it to 0.5%.

Warwick McKibbin is the only panellist expecting the Reserve Bank to change course, expecting one further cut this year and then a series of increases as ballooning debt makes the Reserve Bank and other central banks realise they cut too far, pushing the cash rate back up to 1.5%.

The panel expects a government 10-year borrowing rate of just 1.5%, which is about the lowest it has ever been. A year ago the 10-year bond rate was 2.7%. The ultra low rate will both make it easier for the government to borrow and cut the cost of servicing its existing debt as loans are rolled over.

In further good news for the budget, the panel expects a substantially higher spot iron ore price than does the government, of US$95 a tonne by mid next year instead of the fall to US$55 assumed by the Treasury.

The forecast is somewhat above the Department of Industry’s new July forecast of US$95 a tonne by the end of this year trending down to US$61 by the end of 2020, but are way in excess what was forecast in the budget. A sensitivity analysis included in the budget said that for every US$10 that the iron ore price was higher than budgeted, the government’s tax take would be A$1.1 billion higher in 2019-20 and A$3.7 billion higher in 2020-21.

The panel expects the Australian dollar to remain broadly where it is at just below 70 US cents as the upward push from strong commodity prices offsets the downward push from domestic economic weakness.

Yet despite the iron ore price and lower borrowing costs the panel expects a much weaker budget outcome than the A$7.1 billion surplus forecast in April.

Its average forecast is for a surplus of only $1.7 billion, which is a mere sliver of GDP (0.1%), practically indistinguishable from a deficit of the same amount.

The forecasts come after Finance Department figures for May released on Friday raised the possibility of an early return to surplus in 2018-19. They suggest that surplus is at risk in 2019-20 and beyond, both because of economic weakness and an because of an increasingly urgent need to respond to that weakness through spending or further tax cuts.

Asked whether should the government strive to continue to deliver its promise of a surplus if economic growth remains weak or weakens further, former OECD director Adrian Blundell-Wignall replied bluntly, “of course not”.

The only panellists prepared to defend the continued pursuit of a surplus in the economy remained weak or weakened were Ross Guest, who said it was a worthwhile aim given the steady rise in government debt to GDP ratio, and Tony Makin, who qualified his reply by saying the surplus should be achieved by pruning unproductive expenditure such as industry assistance rather than deferring tax cuts.

Former government minister Craig Emerson regretfully forecast that the government would deliver a surplus whatever the economic circumstances, for political reasons.

The Age and Sydney Morning Herald did not conduct a 2019-20 economic survey.

The Conversation 2019-20 Forecasting Panel

Click on economist to see full profile. Forecasts as of June 24, 2019.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.