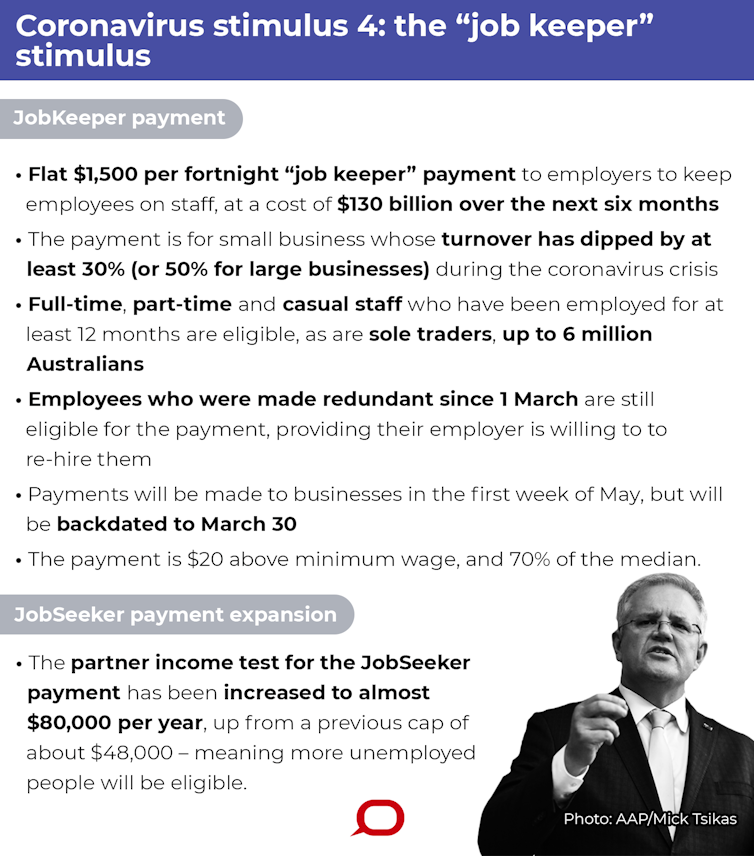

The secret sauce in the government’s A$130 billion JobKeeper payment is that it will be retrospective, in the best possible way.

It’ll not only go to employers who have suffered losses and had employees on their books tonight, March 30, but to employers who have suffered losses and had workers on their books as far back as March 1.

This means employers who have sacked (“let go of”) workers at any time in the past month can travel back in time, pay them as if they hadn’t been sacked, and nab the A$1,500 per employee per fortnight payment.

As the official fact sheet puts it, “the JobKeeper Payment will support employers to maintain their connection to their employees”.

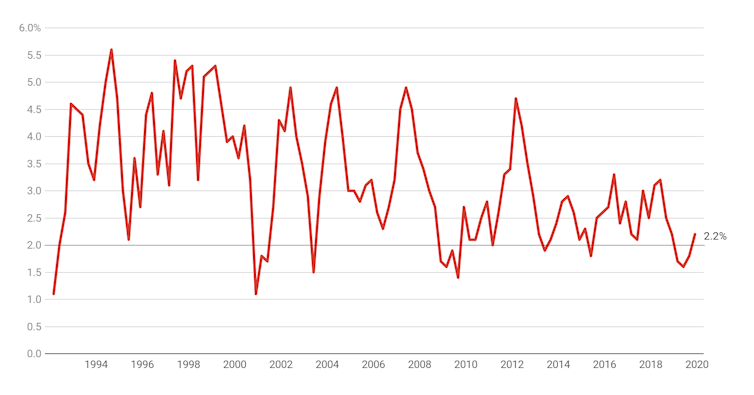

This retrospective connection will add new meaning to the term “revision” when the March unemployment numbers are released.

Not only will the March numbers be liable to being revised a month later as is normal in the light of extra information, but many Australians who were unemployed in March will retrospectively turn out not to have been unemployed.

They will have been retrospectively in paid work.

Read more: Modelling suggests going early and going hard will save lives and help the economy

(And if they have applied for the Centrelink payment of Newstart plus $550 per fortnight, they’ll have to un-apply to avoid what the prime minister referred to as “double counting” rather than the more loaded “double dipping”.)

It gets better. If you have been part-time, or for some other reason on less than $1,500 per fortnight, “your employer must pay you, at a minimum, $1,500 per fortnight, before tax”.

This means you’ll get a pay rise, for the six months the scheme lasts.

If you’ve been let go and then retrospectively un-sacked, you are also guaranteed to get at least $1,500 per fortnight, which in that case might be less than you were being paid, but will be more than the $1,115 you would have got on Newstart (which has been renamed JobSeeker Payment).

If you remain employed, and are on more than $1,500 per fortnight, the employer will have to pay you your full regular wage. Employers won’t be able to cut it to $1,500 per fortnight.

Read more: Which jobs are most at risk from the coronavirus shutdown?

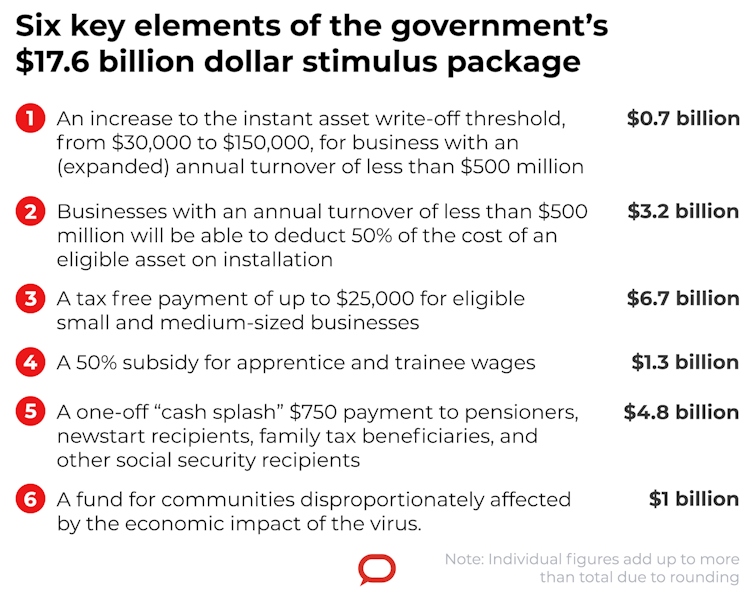

To get it, most employers will have to have suffered a 30% decline in their turnover relative to a comparable period a year ago. Big employers (turnover of $1 billion or more) will have to have suffered a 50% decline. Big banks won’t be eligible.

Self-employed Australians will also be eligible where they have suffered or expect to suffer a 30% decline in turnover. Among these will be musicians and performers out of work because large gatherings have been cancelled.

Half the Australian workforce

The payment isn’t perfect. It will only be paid in respect of wages from March 30, and the money won’t be handed over until the start of May – the Tax Office systems can’t work any faster – but it will provide more support than almost anyone expected.

Its scope is apparent when you consider the size of Australia’s workforce.

Before the coronavirus hit in February, 13 million of Australia’s 25 million residents were in jobs. This payment will go to six million of them.

Without putting too fine a point on it, for the next six months, the government will be the paymaster to almost half the Australian workforce.

Announcing the payment, Prime Minister Scott Morrison said unprecedented times called for unprecedented action. He said the payment was more generous than New Zealand’s, broader than Britain’s, and more comprehensive than Canada’s, claims about which there is dispute.

But for Australia, it is completely without precedent.

Read more:

Australia's $130 billion JobKeeper payment: what the experts think

![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.