What makes the prime minister confident most households will spend A$750 delivered in cash, when they mostly wouldn’t spend the A$1,080 delivered in the form of bonus tax refunds after last year’s budget?

Experience.

Here’s how he put it on Thursday, announcing the economic response to the coronavirus:

Australians will be getting a cheque for $750. Now it’s not for us to tell those Australians how to spend their money, but what we do know from experience is that they will spend that money, and that money will encourage economic activity.

That experience was Labor’s.

On October 11, 2008, Labor announced cash payments totalling between $1,000 and $1,400 per eligible household to stave off a retail recession.

It offered still more in February 2009.

Read more: The coronavirus stimulus program is Labor's in disguise, as it should be

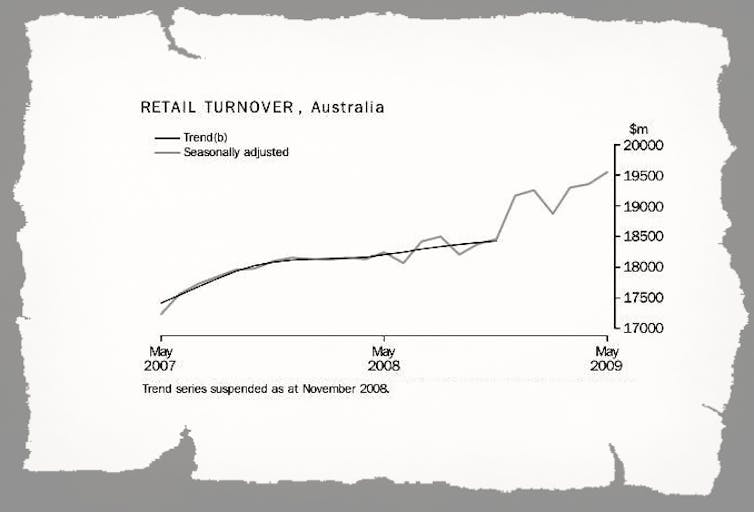

The first cheques went out in December. Spending surged 4% that month after scarcely growing all year. A year on, spending was 5.4% higher than before the cheques went out.

In Japan, the United States, Canada and Germany where stimulus packages were not targeted at consumers, retail spending slipped by 2-3%. In Australia, it surged 5%.

So big was the effect that the payments were staggered by region to ensure cash delivery trucks could top up the automatic teller machines first.

The statisticians collecting retail sales data at the Bureau of Statistics abandoned their usual practice and stopped drawing a trend line.

The jump was impossible to reconcile with the pre-existing trend.

The Treasury had searched the economic literature and determined that cash payments were more likely to be spent than tax cuts, and could be delivered much more quickly.

Six million Australians receive government benefits of some sort, whether they think of themselves as on welfare or not. As recipients of family allowance, childcare support, the pension or even the seniors health card, they are on Centrelink’s books. (Centrelink recently changed its name to Services Australia.)

The payment machine that delivered robodebt can just as easily deliver “robocheques”.

Read more: Cash handout of $750 for 6.5 million pensioners and others receiving government payments

Treasury Secretary Steven Kennedy, who advised Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg to give households cash this time instead of tax refunds, saw the effect at first hand. He was working in Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s office as the good news came through.

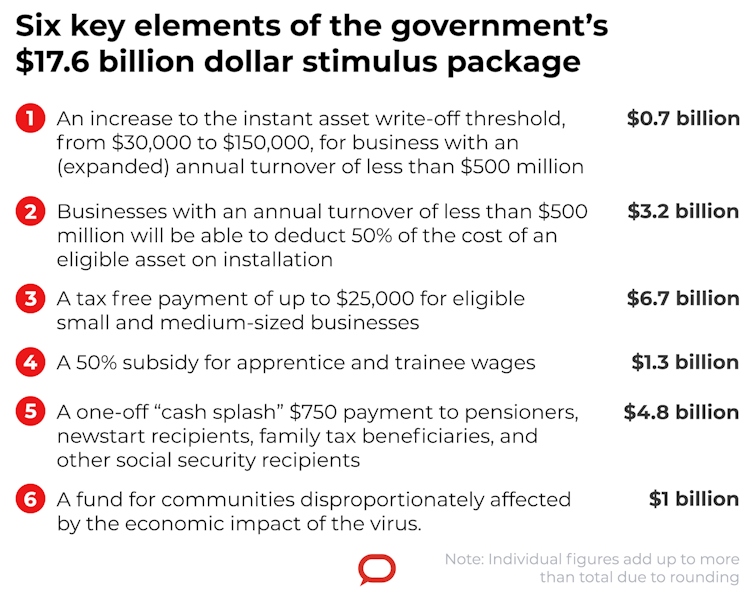

If there is an important criticism of the Morrison government’s (first) coronavirus stimulus package, it would be that it doesn’t concentrate on households enough.

Household spending accounts for 55% of Australia’s gross domestic product, yet payments directed to households make up only 27% of the $17.6 billion the government is spending.

The package has two primary aims. One is to ensure that spending and production don’t shrink in the June quarter after shrinking in the March quarter, triggering what, for better or worse, people call a technical recession.

The Treasury expects it to boost economic activity by 1.5% in the June quarter.

If it does, it should be enough to compensate for the downturn we would have without it, always remembering that we don’t yet know how bad things will get in the three months to June - how many schools and public gathering places will be closed, and how many workers will have to stay home to care for children who can’t go to school or family members who are ill.

Read more: When it comes to sick leave, we're not much better prepared for coronavirus than the US

The second aim is to stop the unemployment rate climbing. When it climbs more than a few points it tends to keep going. In the early 1990s recession it climbed from 6% to 10% in a matter of months.

People who entered the labour force and couldn’t get work were scarred for years.

Labor’s most enduring achievement during the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009 was to stop unemployment climbing above 6%.

That’s what the government’s $11.8 billion of payments to businesses are aimed at, whether delivered in the form of a boosted instant asset writeoff (available only until June 30), accelerated depreciation, payments to cover salaries, or wage assistance for apprentices and trainees.

Morrison wants businesses in the best possible position to hold onto their workers. He wants them to display “patriotism”.![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.