Australia’s leading forecasters expect the Reserve Bank to resist pressure to lift interest rates all year, despite rising interest rates overseas, much higher inflation, plunging unemployment, and financial market traders pricing in two hikes in the next six months.

The 24-person forecasting panel assembled by The Conversation also predicts:

- weaker economic growth

- much lower housing price growth

- next to no growth in the Australian share market

- little or no further inroads into unemployment

- and wage growth so weak that real wages go backwards.

Two-thirds of the forecasting panel expect the Reserve Bank to leave rates ultra low until at least the first quarter of 2023, when it will have a better read on price pressure, wages and the jobs market.

Investors are banking on a different outcome.

Ahead of the Reserve Bank board’s first meeting for the year on Tuesday, securities exchange trading is pricing in an increase in the Reserve Bank’s cash rate from its historic low of 0.10% to 0.25% by June, followed by an increase to 0.5% by August, and two further increases to 1.0% by Christmas.

If that happened, it would leave mortgage rates higher than they were before COVID and before two years of ultra-low interest rates pushed up home prices 25%.

The Bank of England increased its cash rate from 0.1% to 0.25% in December and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand lifted its cash rate in October and November to 0.75%. A 40-year high in inflation is expected to force the US Federal Reserve to lift rates in March.

But China has moved in the other direction, cutting rates and imploring the rest of the world not to “slam on the brakes”.

On balance, no rate hike all year

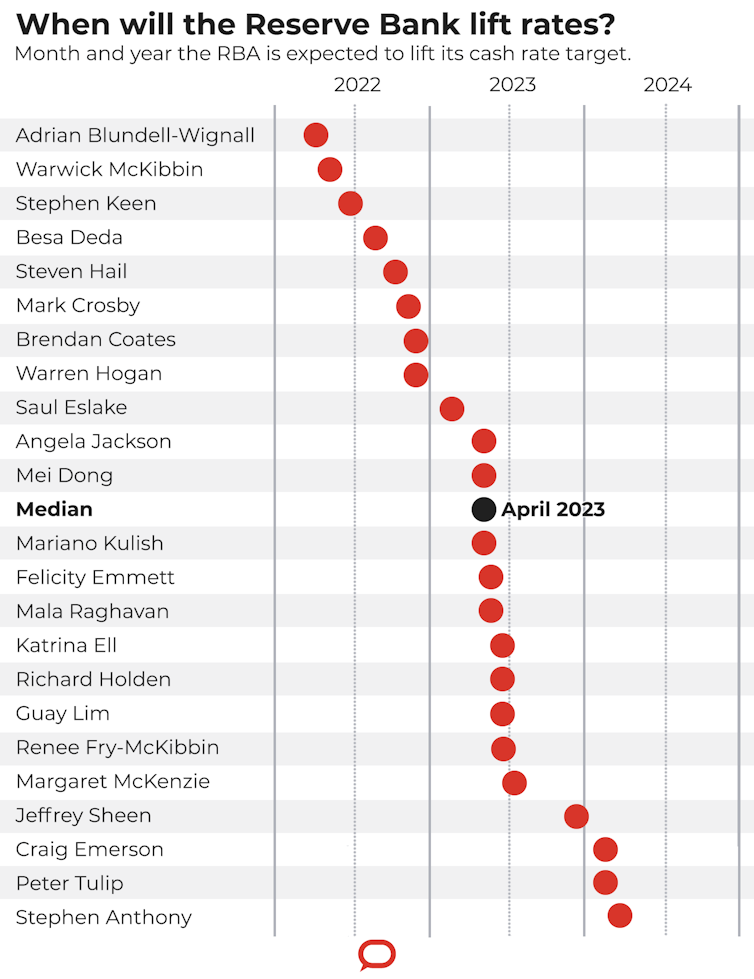

Now in its fourth year, the Conversation survey taps the expertise of leading forecasters in 18 universities and financial institutions, among them economic modellers, former Treasury, OECD and Reserve Bank officials, and a former member of the Reserve Bank board. The panel was surveyed on January 20.

Eight of the panellists predict the Reserve Bank will begin lifting its cash rate this year. One, former OECD official Adrian Blundell-Wignall, expects the bank to begin lifting in March, ahead of the federal election.

But the bulk of those surveyed point to the bank’s target of achieving average inflation “sustainably within” its target band of 2-3% over time, noting that inflation has been well below that band for most of the past five years.

Governor Philip Lowe will outline his thinking after the first Reserve Bank board meeting of the year in an address to the National Press Club on Wednesday.

The panel expects him to suggest he will need to see more than a short-lived burst of higher inflation before he lifts rates.

The panel’s median (middle) forecast is for rate hikes to begin in April 2023. Three panellists, including Peter Tulip, a former research manager at the bank, expect no increase before February 2024.

Inflation not yet a problem

Although inflation has jumped to a four-decade high of 7% in the United States, and although Australia’s headline inflation rate has hit 3.5%, the so-called “underlying inflation rate” targeted by the Reserve Bank hasn’t yet reached the top of the bank’s 2-3% target band.

The panel’s average forecast is that it won’t reach it in 2022 or 2023, and that it will decline in 2023.

Real wages shrinking

But inflation is expected to be high enough to send real wages backwards, perhaps for two consecutive years – a first in the 25-year history of the wage price index.

In 2022 the panel’s average forecast is for wages growth of just 2.7% in the face of underlying inflation of 2.9%, pushing down real wages (buying power) 0.2%.

The panel expects wages growth to remain no higher than prices growth in the year that follows, despite historically low unemployment and labour shortages.

In 2023 it expects wages growth to do no better than underlying inflation at 2.8%.

GDP growth sinking

Economic growth is expected to sink. The panel expects the December 2021 bounce out of state lockdowns to be reported on March 2 to be followed by a March quarter impacted by something akin to “voluntary lockdowns”, as Australians restrict movements in response to Omicron.

Even as immigration and freedom of movement return, the panel expects economic growth to sink back towards 2.5%, which is roughly where it was before COVID and well below the 3-4% common in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Panellists pointed to “increasing social and political discord” and weaker demand from China, along with the “absence of any policies designed to lift productivity growth above dismal pre-COVID rates” as drags on growth, and identified government spending as one of the few supports.

The panel expects China’s economic growth to sink below US economic growth for the first time since the 1970s.

Mei Dong of the University of Melbourne said Chinese growth would suffer from a shrinking working-age population growth, declining employment participation, markedly slower productivity growth and a decision by Chinese authorities to de-emphasise GDP growth as an objective.

Spending held back

The broadest measure of overall living standards, real net national disposable income per capita, is expected to climb more strongly than real wages in 2022, reflecting growth in other sources of income including company profits.

Consumer spending is expected to grow by a healthy 3.7% in real terms, although by nowhere near as much as it would if the boost in saving during the COVID pandemic was fully unwound.

Household saving soared to an unprecedented 23.6% of income in mid-2020 amid concern about COVID, plunged down to a still-elevated 11.8% in mid 2021 after restrictions eased, and then soared again to 19.8% as Delta took hold.

The ratio is expected to remain at an elevated 12% throughout 2022, well above the few per cent common in the decades leading up to COVID, as households hang onto rather than spend income, uncertain about the future.

In December, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg spoke about the unusually high saving rate as a source of future spending, saying it was “a lot of damn money that’s been accumulated”. The panel’s forecasts suggest that accumulation will continue.

The panel expects non-mining business investment to grow strongly throughout 2022, although in response to budget measures rather than what economist Stephen Anthony describes as structural drivers moving in the other direction.

Panellist Mark Crosby says investment should slow towards the end of 2022 as the prospect of higher interest rates dents the construction industry.

Unemployment with a ‘4’, but not a ‘3’

Few of the panellists expect Australia’s unemployment rate to fall much below its present 4.2% in the two years ahead, despite what former ANZ economist Warren Hogan describes as the strongest labour demand Australia has ever seen.

He says the problem is the skills employers are looking for don’t match those of job-seekers and the workers likely to become available in the years ahead.

Janine Dixon says businesses are putting more people on their payrolls to cover sick leave and isolation leave, making it likely there has been an increase in underemployment.

In releasing the December budget update, Treasurer Frydenberg forecast “the addition of around one million jobs” between October 2021 and mid-2025.

It’s a projection broadly endorsed by the panel, although mainly because they believe that’s what population growth is likely to deliver.

Mark Crosby described it as a “pretty ordinary outcome given the rate of jobs growth seen prior to the pandemic”. Much would depend on migration. The more migrants, the more extra jobs.

Weaker home price growth

After a year in which national housing prices soared 22%, the panel is expecting more sedate growth of 6.5% in Sydney and 6.1% in Melbourne.

Katrina Ell of Moody’s Analytics believes the market has already peaked. She says mortgage rates will creep higher this year regardless of whether the Reserve Bank lifts official rates, and measures put in place by the Prudential Regulation Authority are starting to cramp investor interest.

Warren Hogan disagrees, seeing investors driving the next phase of the housing market. He says cashed-up upper middle to high income households will try to protect their wealth against rising inflation by buying real estate.

Subdued markets

In aggregate, the panel expects the exchange rate to stay broadly where it is at 71 to 72 US cents in 2022, and expects the ASX200 share price index to end the year about where it began, after climbing 13% in 2021 and sinking 6% in January.

They expect the iron ore price to fall from US$137 per tonne to US$98.

The panel:

This Conversation survey is the first not to include the views of Griffith University professor and former IMF and Treasury official Tony Makin who passed away suddenly in November, aged 66. His contributions were greatly valued.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.