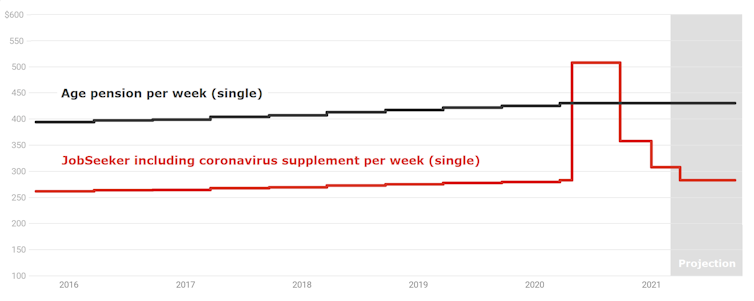

Once about as high as the pension, the JobSeeker (Newstart) unemployment payment has fallen shockingly low compared to living standards.

It’s now only two thirds of the pension, just 40% of the full-time minimum wage and half way below the poverty line.

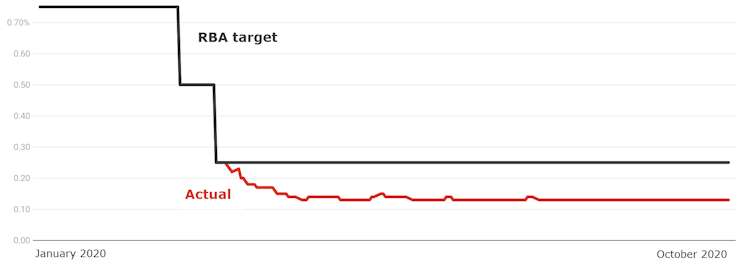

JobSeeker has fallen relative to other payments because while the pension and wages have climbed faster than prices, JobSeeker (previously called Newstart) has increased only in line with prices since 1991.

In an apparent acknowledgement that JobSeeker had fallen too low, the government roughly doubled it during the coronavirus crisis, introducing a supplement to enable people to “meet the costs of their groceries and other bills”.

But that supplement is being wound down, from A$225 per week to $125 on September 25, and again to $75 on January 1, before expiring on March 31.

After March, the single rate of JobSeeker (including the $4.40 per week energy allowance) will drop back to about $287.25 per week.

JobSeeker vs age pension

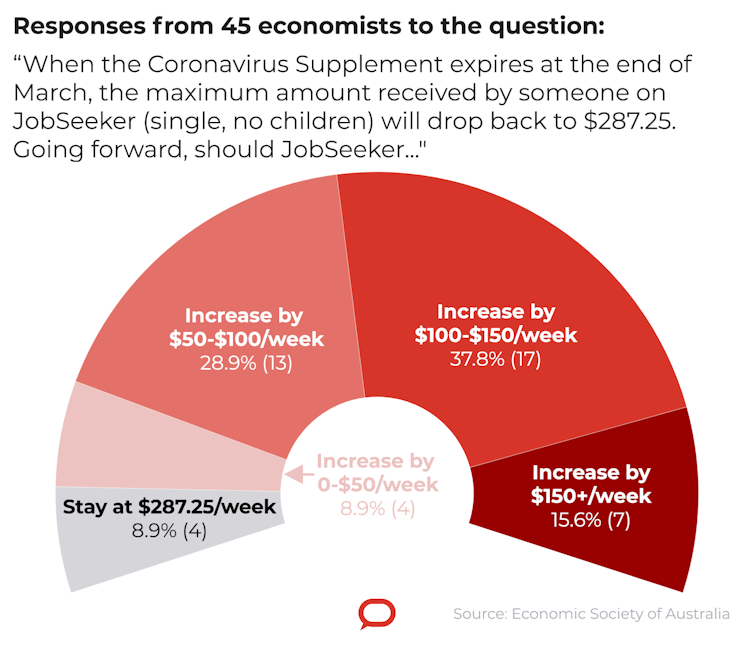

Ahead of a decision about any permanent increase expected early next year, The Conversation and the Economic Society of Australia asked 45 of Australia’s leading economists where they thought JobSeeker should settle.

Only four think it should revert to $287.25 per week.

All but eight want a substantial increase. More than half (24 out of 45) want an increase of at least $100 per week.

The results suggest the economists would be dissatisfied with a decision to merely increase JobSeeker by $75 per week in line with the supplement that is due to expire at the end of March.

The 45 members of the society’s 57-member panel who responded include Australia’s preeminent experts in the fields of microeconomics, macroeconomics economic modelling, labour markets and public policy.

Among them are former and current government advisers, a former member of the Reserve Bank board and a former member of the Fair Work Commission’s minimum wage panel.

Read more: Top economists back boosts to JobSeeker and social housing over tax cuts in pre-budget poll

Many want an increase of about $150 a week to bring JobSeeker close to the age pension and 50% of median income.

Curtin University’s Harry Bloch asked (rhetorically) whether unemployed people had “lower needs than those on the aged pension”.

Labour market specialist Sue Richardson said keeping payments so low that people lost dignity and hope and suffered material deprivation hurt not only the people who were unemployed, but also the thousands of children who grew up in their households.

A scant incentive to shirk

She knew of no evidence that suggested a low rate of JobSeeker increased the likelihood of an unemployed person getting a job.

Jeff Borland said even if JobSeeker was increased by $125 per week, those on it would still earn less than all but 1% of full-time adult workers and would face plenty of remaining financial incentives to get paid work.

In research to be published in The Conversation on Monday he examines a real-life experiment: the temporary near-doubling on JobSeeker between March and September, and finds it played no role in creating unfilled vacancies.

Read more: New finding: boosting JobSeeker wouldn't keep Australians away from paid work

Emeritus Professor Margaret Nowak said JobSeeker had been driven to the point where it denied unemployed Australians the shelter, food and transport they needed to find work.

Former Liberal party leader John Hewson described the failure to adjust JobSeeker for three decades as “immoral”, and a national disgrace driven by “little more than prejudice”.

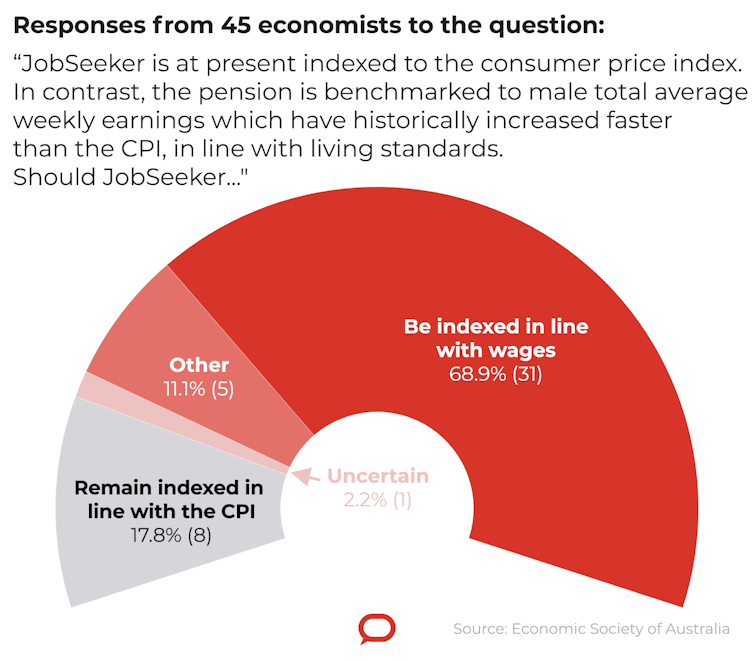

Going forward, there was overwhelming agreement among those surveyed that once JobSeeker was restored to an acceptable level, it should be linked to wages (in line with the pension) rather than increase with prices as before.

Two thirds of those surveyed want JobSeeker increase in line with wages, and of those who do not, several want the pension to increase more slowly in order to ensure the two move in sync.

Gigi Foster and Geoffrey Kingston propose a half-way house – increases in both the pension and JobSeeker halfway between increases in the consumer price index and wages.

Wages determine living standards

Others suggest practical measures to make JobSeeker better at getting Australians into jobs. Beth Webster suggests reducing the rate at which JobSeeker cuts out with hours worked to encourage part-time workers to take on more hours.

Tony Makin suggests a relocation allowance to help people take on jobs distant from their current place of residence.

Read more: 'If JobSeeker was cut, the unemployed would be picking fruit'? Why that's not true

None of the economists surveyed expressed concern about the budgetary cost of restoring the relative position of JobSeeker, estimated by the Parliamentary Budget Office to be $4.8 billion per year for an increase of $95 per week.

Several expressed a desire to put the issue behind them, increasing JobSeeker to a reasonable proportion of the pension or median wage and leaving it there so that, in the words of Saul Eslake, “this issue never arises again”.

Individual responses

![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.