NSW is doing what Labor’s Bill Shorten could not – explaining why Australia’s capital gains tax concession is knocking first home buyers out of homes.

Shorten went to the 2016 and 2019 elections with a plan – Labor would halve the capital gains tax concession used by landlords who buy and sell properties.

In much the same way as he was unable to sell his (now modest by international standards) plan to make half of all new car sales electric by 2030, he was pilloried by Morrision and before him Malcolm Turnbull for a policy they said would smash house prices.

All Shorten was proposing was to wind back the capital gains tax exemption (which exempts from tax half of each profit made from buying and sell real estate and other assets) for future transactions only. The exemption would stay in place for everything already bought.

In the face of an overblown debate about whether or not it would smash house prices (Morrison’s department had quietly warned such claims were “not consistent with our advice”) the Labor leader found himself defending modelling about prices rather than outlining what his policy would actually do.

And he lost, twice.

Now, as we prepare for yet another election, the NSW Coalition government has done what Australia’s Labor opposition could not – make a cogent argument for winding back the capital gains tax concession, saying it “pushes first home buyers out of the market”.

Elbowing first home buyers aside

In a submission placed quietly on the federal government’s housing inquiry website late last week the NSW government argued that if the concession was cut, housing would be used “more for accommodation needs than investment needs”.

Here’s the line of thinking it set out, the line Shorten was never able to get across.

The income made from capital gains – from buying something, holding it, then selling it at a profit – is taxed differently from the income made from work or running a business. Only half of it is taxed.

Prime Minister John Howard and his treasurer Peter Costello were responsible for the change, introduced in 1999 in the leadup to the introduction of the goods and services tax in 2000, but with less fanfare.

Before then capital gains were taxed in the same way as other income (what they are subject to is income tax, there is no such thing as a separate capital gains tax).

But before then only the portion of each gain over and above the rate of inflation was taxed, so that people weren’t taxed on a profit that would have no real value.

The change, introduced after an inquiry that found it would “encourage a greater level of investment, particularly in innovative, high-growth companies” was to instead tax only half of each capital gain.

It was sold as a small change. A few years earlier, inflation had been big, around 8% per year, meaning that after five or so years only half of each profit would have been taxed in any event.

But inflation had since dived to a barely-noticeable 2%, where it has stayed for most of the past 20 years, making a guaranteed exemption from tax of half of each capital gain made trading property way over the odds.

It was, as economist Rory Robertson told his clients at the time, “almost as though the Australian tax system has been screaming at taxpayers to gear up to earn increased capital gains rather than to work harder to earn increased wages”.

Instead of pouring into high-growth companies, as Howard’s inquiry said it expected, the money flooded into housing, which was easier to borrow for.

Rushing into real estate rather than shares

As Reserve Bank assistant governor Luci Ellis told a parliamentary inquiry, it was “more profitable to negatively gear property, because you can gear it more”.

To buy properties quickly, real estate investors needed to buy properties that would have otherwise been bought to live in.

It pushed up prices, but that wasn’t all it did.

As the NSW submission to the current housing inquiry says, the most significant impact was “the displacement of owner occupiers (including first home buyers) from home ownership by tax-advantaged investors, predominantly those already on higher incomes”.

In its words

by encouraging investors to buy and hold property, the 50% capital gains discount increases investor demand for housing and pushes first home buyers out of the market

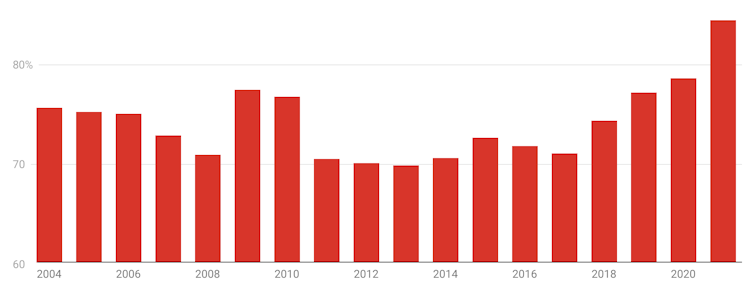

Before capital gains tax was halved and Australians dived into becoming landlords, more than 70% of Australian households owned the home in which they lived and one quarter rented.

At the latest count (itself four years old) only two thirds owned the place in which they lived and one third rented.

Labor has new friends

And properties are less well used. Because income from rent is no longer the chief motivation for holding property (these days most rental properties make a rental loss whereas before the capital gains tax change most made a profit) the NSW government believes more are remaining empty.

Now, when the capital gains from holding properties can be measured in hundreds of dollars per day, it would be an ideal time to wind back the capital gains tax discount. Its absence wouldn’t much hurt.

And it’s easy to forget that wasn’t what Labor was proposing. Shorten (twice) put forward something far more modest – leaving the tax discount for existing investments untouched and halving the discount for future investments.

It’s no longer Labor policy, but it was backed by the head of the Coalition’s Commission of Audit and the head of its financial system inquiry.

And it was of interest to the Business Council of Australia which pointed out that the discount “can distort investor behaviour, particularly at a time of rapid capital gains, such as in a housing or equity boom”.

Morrison’s opposition to it was hard to justify at the time. It’s harder now.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.