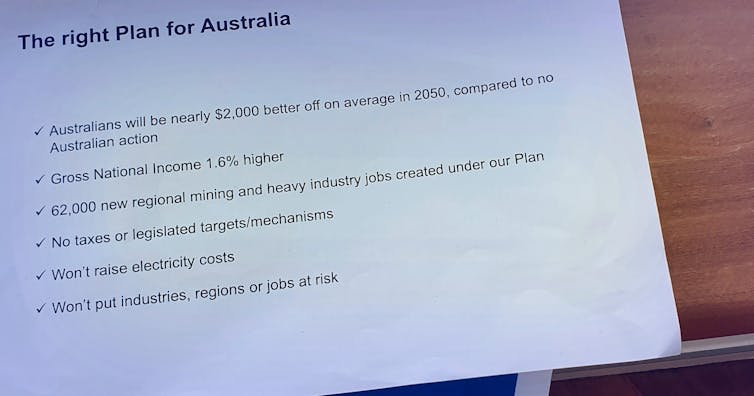

The government’s decision to target net-zero emissions by 2050 will leave each Australian nearly A$2,000 better off by then compared to no Australian action.

That’s what we were told in a six-point summary of the government’s economic modelling released at a press conference on Thursday October 26, days before the prime minister left for the Glasgow climate talks.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison said at the time the actual modelling would be released “in due course”, later clarifying that it might not be released for a fortnight, after which the Glasgow climate talks would be almost over.

The 100-page summary of modelling prepared by the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources and the consultancy McKinsey & Company was released on Friday afternoon as the climate talks were concluding.

The document tells us both how the $2,000 figure was arrived at and the question that was asked.

The question that was asked

McKinsey and the department were asked to compare economic outcomes in 2050 after 30 years of “no Australian action” with economic outcomes in 2050 after 30 years of “the plan”.

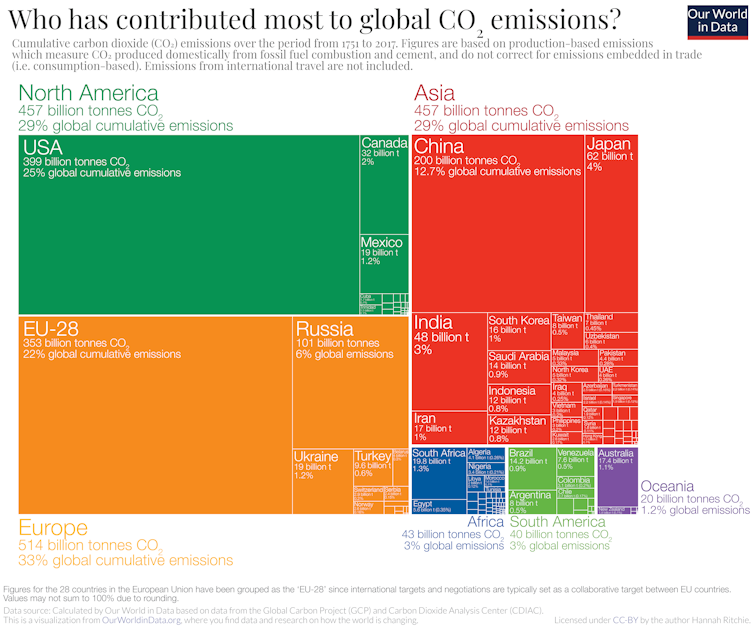

“No Australian action” meant that every developed country other than Australia cut its emissions to net-zero by 2050, and all of the world apart from Australia did whatever else was needed to hold global warming to 2°C.

Australia would find it harder to raise money because of its reluctance to commit to net-zero (meaning its borrowing costs would incorporate a “risk premium”) and would get access to only those improvements in technology that were available elsewhere.

“The plan” involved Australia continuing “to invest in technological breakthroughs,” acting as an “enabler to support consumer choice and voluntary adoption of other technologies”.

Australia would adopt a target of net zero by 2050, escaping a risk premium.

The government would invest more than A$21 billion to support the development and deployment of low emissions technologies including clean hydrogen, ultra low-cost solar, energy storage, low-emissions materials, carbon capture and storage and soil carbon to 2030, and continue to play a “direct role” beyond that.

Otherwise, emissions would be reduced on “a voluntary basis”.

Importantly, and so the size of the voluntary action can be incorporated into the modelling, the voluntary emissions reductions are assumed to be the same as what would be expected if Australians faced a carbon price (or tax) that climbed to A$24 per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2050.

Emitters finding it hard to cut emissions as much as they or consumers or investors wanted would be able to buy international “offsets” (overseas emissions reductions) at a price that would climb to A$40 per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2050.

$2,000 per person better off

The modelling concludes that under “the plan” each Australian would be almost A$2,000 better off in 2050 compared with under “no Australian action”.

That’s $2,000 per year in so-called gross national income per capita, but it’s less impressive than it sounds. The latest stats have gross national income per capita approaching A$80,000.

That’s not what’s received by any one individual, but what’s received by businesses and all sorts of other entities averaged across the population.

Compounding economic growth means that by 2050 that dollar sum will be two to three times as big, against which (and given all the uncertainties) a projection of an extra $2,000 amounts to little difference.

A reasonable way to interpret the modelling is that, compared to “no Australian action”, the “plan” won’t impose significant costs on Australians.

Where the $2,000 comes from

Which isn’t to say that there won’t be big costs.

The world will move away from coal and liquefied natural gas – two of Australia’s biggest exports – but what is assumed is that will happen in any event, under both “the plan” and the “no Australian action” scenarios.

Unless you were to assume that the rest of the world won’t pull its weight in getting to net-zero (and the modelling does not assume this) Australia not pulling its weight does almost nothing to rescue its exports.

The $2,000 comprises two parts. $375 is the benefit to Australia of avoiding investors being less keen to invest in a country that isn’t pulling its weight.

The modelling says Australia would score an average of 5.5% less investment per year under the “no Australian action” scenario compared to under “the plan”.

The other $1,625 derives from the development of new industries, spurred in part by the government’s $21 billion, the most important being hydrogen production which by itself would lift national income per person by about $1,000 of the $2,000.

What was released Friday afternoon is not the modelling itself but a government-authored “summary”.

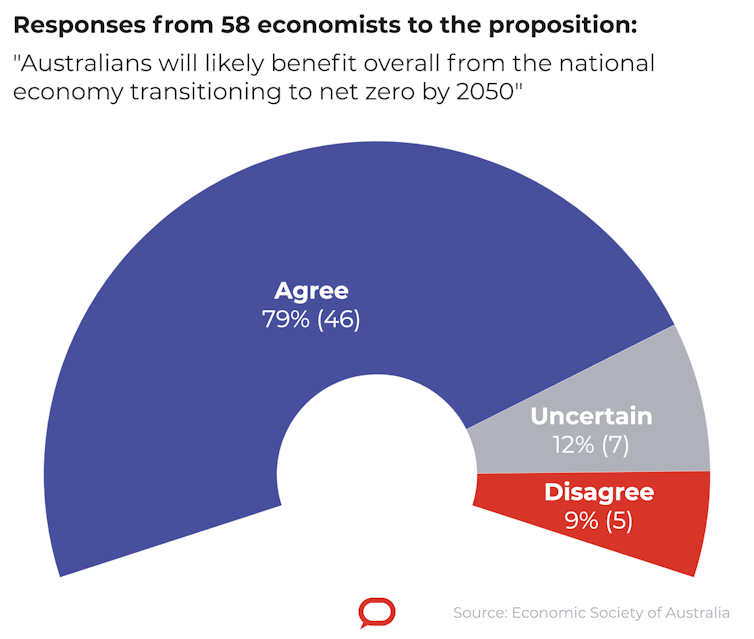

Although it is difficult to compare the McKinsey modelling with the Treasury modelling prepared for the Gillard government ahead of the 2012-2014 carbon pollution reduction scheme, it is notable that both arrived at a similar conclusion: that over time, action to reduce emissions will cost Australia little.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.