There are the Boxing Day sales, and there was this week’s rush of extremely cashed-up investors desperate to get a slice of this week’s rare 31-year government bond auction.

What’s a bond? What’s a bond auction? We’ll get to those shortly.

First, just know that the government received A$36.8 billion of bids, $20 billion of them within hours of opening the two-day auction on Monday.

It had been wanting to move $15 billion, and could have moved that much again.

$15 billion makes it the third biggest bond sale in Australian history. The two bigger were recent – a $19 billion ten-year bond sale in May and a $17 billion five-year bond sale in July.

Each sale nets the government money it won’t have to pay back for five, ten or 31 years at rates of interest that until recently would have been unthinkably low.

Read more: More than a rate cut: behind the Reserve Bank's three point plan

The 31-year bond went for 1.94%. That means the foreign and Australian investors who bought them (including Australian super funds) were prepared to accept less than the usual rate of inflation right through until 2051 in return for regular government-guaranteed interest cheques.

Investors who bought ten year bonds were prepared to accept only 0.92% per year, investors who bought five year bonds, only 0.40%.

What’s a bond?

Even bond traders find it hard to get a handle on what bonds are. In his novel Bombardiers, author Po Bronson writes a scene where a bond trader refuses to work any more and demands to see an actual bond, “any kind of bond”.

He tells his boss he can’t sell bonds “if he’s never seen one”.

Like many things that used to exist physically, they’re now mainly numbers on screens, but it helps to get a picture.

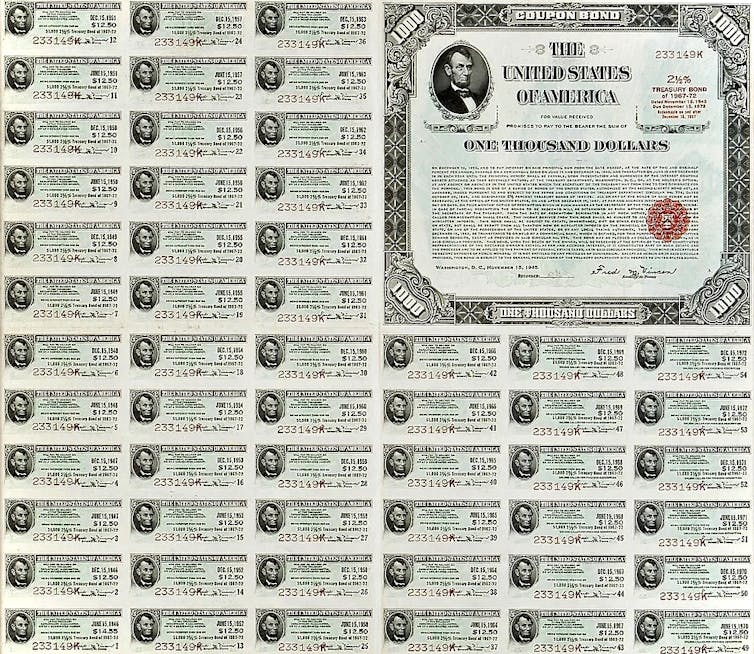

This one is a US 27-year bond from 1945.

The biggest part of the paper is a promise to repay the US$1000 it cost, in 27 years time.

The smaller rectangles are called coupons, and each year the owner can tear one off and take it in to get 2.5%.

If the owner wants to sell the bond to someone else (and bonds are traded all the time) it’ll be sold with one coupon missing after one year, two coupons missing after two years, and so on.

When rates fall, prices rise

The price of a bond will vary with what’s happening to interest rates. If they are falling, an existing bond, offering returns at old rates, will become more expensive and can be sold at a profit. If they go up, an existing bond will become worth less and have to be sold at a loss.

It leads to confusion. When bond rates fall, bond prices rise, and visa versa.

Read more: 'Yield curve control': the Reserve Bank's plan for when cash rate cuts no longer work

For half a decade now bond rates have been falling. They’ve fallen further during the COVID crisis, making bonds a doubly good investment. They offer superannuation funds and others certainty at a time when everything seems uncertain, and if rates continue to fall they increase in value.

It is an indictment of our times that so many investors want them. The government’s office of financial management is going to need to sell an extra $167 billion over the coming year. The rush to buy suggests it could sell more.![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.