Josh Frydenberg has the opportunity to become a transformational Australian treasurer. He has been bequeathed a set of circumstances that comes along rarely.

He has already shown himself able to shift the debate on important topics in order to achieve the previously unthinkable.

Most recently he did it with Google and Facebook, getting them to pay news providers for content using legislation that led the world in its breadth and force.

It’s actually the second time Frydenberg has taken on big tech. As assistant treasurer in 2015 he championed a “Netflix tax” on overseas-based suppliers of online services. They would be required to collect and pass on goods and services tax, just like Australian retailers.

It was a tax experts told him big tech might never pay.

Frydenberg has shown boldness before

Opportunities like the much bigger one in front of him now don’t come along often because Australia isn’t in recession often. Three decades ago in the early 1990s Australia’s then Reserve Bank governor Bernie Fraser seized its mirror side.

In the wake of an appalling recession that had destroyed both jobs and inflation, Fraser opted to finish the job and drive a stake through the heart of inflation.

A biography of then treasurer Paul Keating quotes Fraser as saying “we’ve got the inflation rate down and we are damn-well going to keep it down”.

At the first hint of a resurgence in inflation as the economy got back on its feet Fraser rammed up interest rates an extraordinary 0.75 percentage points in August 1994, then another 1.00 percentage points in October, and a further dizzying 1.00 percentage points in December.

Job finished, inflation has remained tamed ever since, never again returning to the 8% and 10% common in the 1980s.

Recessions create opportunities

Frydenberg’s opportunity is to drive a stake through the heart of unemployment.

From the end of the second world war right through to the mid 1970s Australia’s unemployment rate averaged just 2%. From then onwards until today it has averaged 6.8%, an embarrassment in a country capable of much, much better.

How much better?

The Reserve Bank’s pre-COVID estimate of Australia’s so-called non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) was 4.5%. NAIRU is the rate below which it is thought inflation and wage growth might start to climb.

Read more: Why the unemployment rate will never get to zero percent – but it could still go a lot lower

If correct, the estimate means there is no danger whatsoever in pushing Australia’s unemployment rate down from its present 6.4% to 4.5%, or lower. We won’t know how much lower until we try. Pre-COVID, US unemployment got to 3.5%.

Far from danger, there would be a huge payoff in permanently lowering the rate of unemployment Australia regarded as acceptable.

At an unemployment rate of 4.5%, an extra 255,800 Australians would be in work and earning money, providing services and paying tax. The government could save $4 billion per year in JobSeeker payments.

We could go for broke

Frydenberg should actually aim for a much-lower unemployment rate than 4.5%.

Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe does not say 4.5% would accelerate inflation, he says he doubts whether anything above 4.5% would accelerate inflation.

And Lowe says this notwithstanding the view of the secretary to the treasury that the recession has pushed up NAIRU to around 4.75% to 5% as people who have lost their jobs have become less employable.

But here’s the thing. NAIRU is the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment — the rate that keeps inflation and wage growth constant.

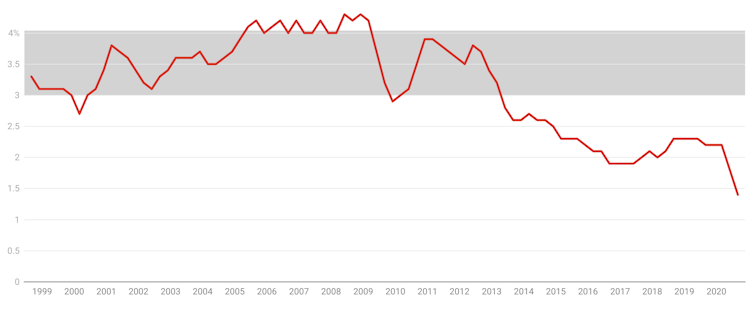

Wage growth, at 1.4% and inflation, at 0.9% are too low. We need them to accelerate. Frydenberg and the Reserve Bank have agreed to target inflation of 2-3%. It’s a target that would normally mean wage growth of 3-4%, where wage growth hasn’t been for the best part of a decade.

Wage growth below par for years

To get inflation and wage growth back up to where we want them we are going to need an unemployment rate well below the oddly-named NAIRU — well below 4.5% — for quite some time.

In his new book Reset, economist Ross Garnaut says we should be aiming for an unemployment rate of 3.5%.

He says on the way down there would be time to adjust the target “up when high and accelerating inflation becomes a matter of concern, or down (further) if we approach 3.5% without inflation accelerating dangerously”.

As in the US, we don’t yet know how low we can safely push unemployment, but it might turn out to be very low indeed.

To get there Australia’s government will have to keep spending, and learn to live with big budget deficits and big debt.

Garnaut says to not do so would be a false economy, condemning us to “endless increases in our public debt-to-GDP ratio because we wouldn’t be producing the GDP we were capable of”.

The government would fund the crushing of unemployment by selling bonds to the Reserve Bank directly, bypassing financial markets in order to avoid putting further upward pressure on the dollar.

Low risk, long payoff

To the extent that the continuing flood of bonds further eased mortgage interest rates (which it mightn’t much, because the bonds would be long-term) the Prudential Regulation Authority would have to crack down on investor and interest-only loans as it did successfully before the COVID crisis in order to restrain house prices.

Garnaut believes there will also be a need for less-pleasant reforms to restore the prosperity Australia is capable of, but he says they will only gain widespread acceptance if it is known that anyone who wants a job can get a job — whether that’s at an unemployment rate of 3.5%, the 2% Australia once had or the 1% New Zealand had.

The COVID recession and rapid recovery from it have handed Frydenberg an opportunity to relentlessly drive down and crush unemployment — to finish the job.

If he grabs it he will be remembered as the treasurer who changed Australia, perhaps forever.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.