Last year COVID-19 seemed simple. It was horrific, but the arguments about what to do were fairly straightforward.

On one side were people rightly horrified by its rapid spread who wanted us to stay at home and stay away from school and work and socialising in order to save lives.

On the other side were people concerned about the costs of those measures — to jobs, to education, to freedom, to mental health, and to other lives (because if we used too much of our health system fighting COVID-19, other lives might fall through the cracks).

And through it all came a kind of consensus.

The concern about non-COVID deaths turned out to be overblown. Last year Australia recorded fewer than normal doctor-certified deaths, in part because the COVID restrictions stopped deaths from influenza, and in part because they snuffed out COVID-19 early, ensuring hospitals weren’t overwhelmed.

Last year, we didn’t have to choose

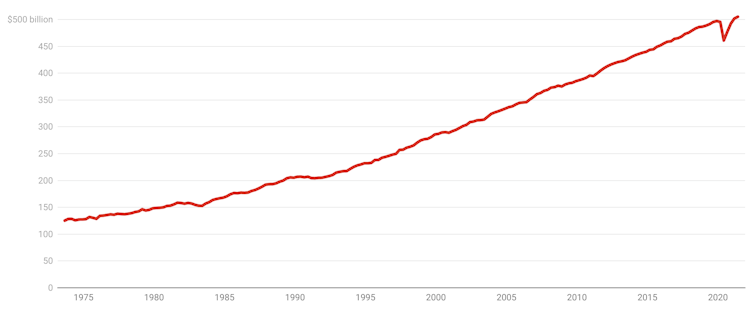

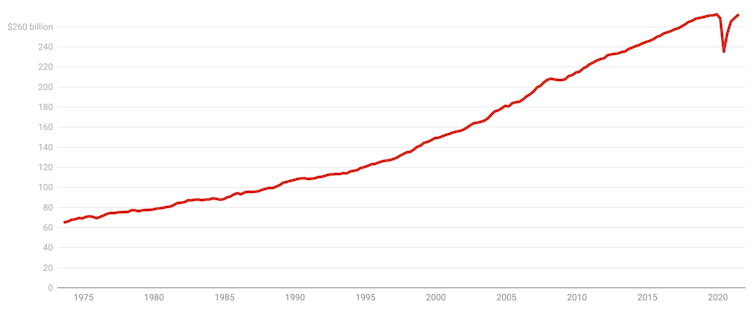

Concern about jobs also turned out to be overblown. By locking down hard and early, and paying employers to keep on staff (through JobKeeper) we ensured the lockdowns would be short-lived, with light at the end of the tunnel.

In none of the states for which there is data was there an increase in suicides.

The insurance company ClearView told a parliamentary committee this June its research found things were better than expected in part because of the universal nature of the pandemic. Everyone knew “everyone was in this together”.

Another reason was telehealth. It was easier to get help than before.

Read more: 7 lessons for Australia's health system from the coronavirus upheaval

And students returned to school sooner than they would have had the lockdowns had been weaker or started later, leaving much of their education intact.

The consensus was that by locking down hard and early we got the best of both worlds — near-elimination of COVID-19 and a quick return to normal life. Anyone who remembers Christmas last year remembers how normal it felt.

Economics is called the dismal science in part because it is about hard choices — situations where we can’t have our cake and eat it too. Last year it seemed as if COVID wasn’t one of them. Starving the virus early gave us both one of the world’s lowest death tolls and one of its shortest recessions.

Hard choices are back in sight

And then came Delta.

Far more contagious than the original, and with fewer immediate symptoms (making it harder to trace) the Delta variant became almost impossible to get on top of in the two big states where it took hold.

And without very high vaccination rates — in the view of the Grattan Institute significantly higher than either the NSW, Victorian or Commonwealth governments are targeting — it became all but impossible to reopen without condemning Australians to COVID deaths.

The new reality is plunging us back toward the territory economists call their own — the world of hard choices.

If the lockdowns don’t end (and there is no sign they can end any time soon without costing lives) education and mental health and jobs will indeed suffer.

There’s only so long businesses can hang on without pulling the pin.

We are getting closer to having to trade off lives against freedoms; getting closer to having to decide how many COVID deaths and how much COVID illness we are prepared to live with in order to return to something more like normal living.

Last week’s NSW “roadmap to freedom” implicitly made those tradeoffs.

Calculations prepared by the Treasury and the Grattan Institute make them more explicit.

There are few important things to note.

One is that we might yet be able to get the best of both worlds. We might yet be able to effectively eliminate the delta strand, restoring both health and freedoms (as we did with the earlier strand).

It won’t happen if we ease restrictions before transmission has stopped, as some states are planning to.

Lockdowns without end are unsustainable

Another is that unending lockdowns are untenable. While last year’s lockdowns didn’t do the psychological and health and educational damage that was feared, lockdowns without end would.

One type of damage clearly evident in the comprehensive report on last year’s lockdowns from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare is family and domestic violence. The longer lockdowns continue, the longer elevated violence is likely to continue.

And another thing to note is that in a world where we have to make tradeoffs there are no particularly good options. Allowing the disease to spread in order to restore freedom of movement would itself curtail freedom of movement.

Read more: Economists back social distancing 34-9 in new poll

An analysis across US states suggests 90% of last year’s collapse in face-to-face shopping was due to fear of COVID rather than formal COVID restrictions. That fear will grow if we lift restrictions and COVID spreads.

The Grattan Institute would lift lockdowns only when 80% of the entire population has been double vaccinated (not 70-80% of people aged 16+ as the NSW and national plans envisage, which amounts to 56-64% of the population).

Grattan believes its plan would cost 2,000-3,000 lives per year; a cost it believes the public would accept because it is similar to the normal toll from flu.

The NSW and national plans (Victoria’s isn’t spelled out) would cost much more.

No option is particularly good

The Commonwealth Treasury finds, perhaps counter-intuitively, that an aggressive lockdown strategy that saved more lives would impose lower economic costs (about A$1 billion per week lower) in part because it would end up producing fewer lockdowns.

They are the sort of calculations we hoped never to have to make.

There’s still a chance we might not. With a Herculean effort NSW and Victoria could yet join Taiwan, New Zealand and every other Australian state in being effectively COVID-free. But they are running out of time.

Read more: NSW risks a second larger COVID peak by Christmas if it eases restrictions too quickly

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.