Failure is only the beginning.

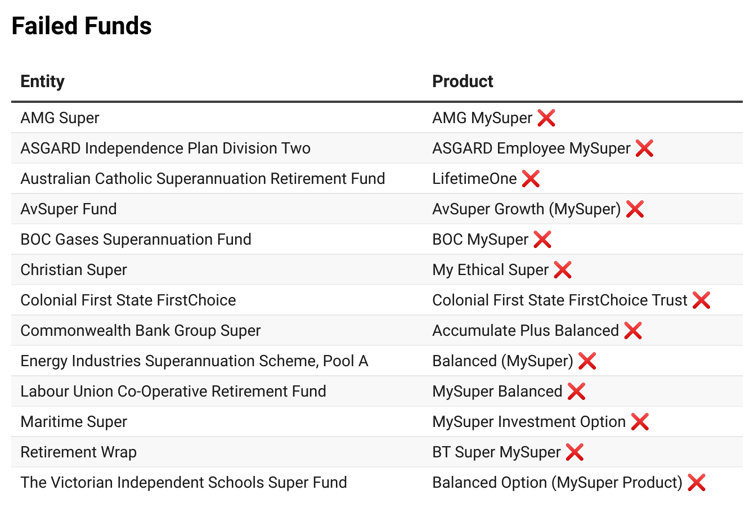

Thirteen of Australia’s 80 closely-regulated MySuper superannuation funds have failed the APRA performance test.

There’s a fair chance you are among the one million people in them.

The results were made public on Tuesday and handed to the funds on Monday. From here on — for the people who run those funds — it’s about to get worse.

APRA is the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority. Landmark reforms introduced in response to a devastating Productivity Commission report into the “mess” that is much of Australia’s super industry require APRA to rate each MySuper fund (and from next year most other funds) with a pass or a fail according to how they have managed their members’ money.

To fail — as one in six funds have — would require the fund to have for seven or eight years managed its members’ funds so badly that when judged by its own stated investment strategy, those members would have been better off investing in the broad categories of assets themselves and paying the managers to stay away.

Under the rules, which go by the name Your Future, Your Super, funds can only be given a “pass” or a “fail”. Those that fail are required to write to their members.

Letters humbling

The letters, which have to be delivered within 28 days, and which APRA will check, are humiliating.

“Hello [fund member],” they begin. “Your superannuation product has performed poorly under an annual performance test”.

As a result, we are required to write to you and suggest that you consider moving your money into a different superannuation product.

By switching into a better performing product, you can potentially save thousands of dollars more for retirement. For example, by earning 1% higher net return over a 30‑year period, you could be 20% better off at retirement.

At the bottom of each letter is a QR code members can use to go to ato.gov.au/yoursuper to compare funds’ performance. If members log in with their MyGov account they will be told exactly what super they have and where it is (I’ve tried it and it works) and get a comparison tailored to their circumstances.

The 13 funds forced to send out these letters will be lucky to see out the year. Once a fund suffers withdrawals and has to pay out members it performs even worse. Within months, many will be taken over.

Killing season

Those that remain are unlikely to last a second year. Once a product fails for two consecutive years (most that fail in the first year are expected to fail in the second) it will be prohibited from accepting new members, which means it’ll be killed.

It may or may not be relevant, but the driving forces behind the revolution are women. Women typically do much worse out of super than men.

Karen Chester chaired the Productivity Commission inquiry that quantified the hundreds of thousands of dollars lost in retirement by each worker who stays in a dud fund, and came up with the first draft of the performance test.

Kelly O'Dwyer, as financial services minister championed it, as did her successor Jane Hume.

In charge of policing the rules is APRA executive board member Margaret Cole, who was known as the “enforcer” during her time as director of enforcement and financial crime at the UK Financial Services Authority.

On Friday she declared bluntly that Australia had too many funds, too many persistently underperforming funds and too many with fees that remain too high.

Industry funds among those failed

Among the chronic underperformers now facing a death spiral are five industry funds — two of them run by members of Industry Super Australia, the organisation that represents funds set up “only to benefit members”.

Rather, they were members. Maritime Super left just ahead of the results. LUCRF, originally set up by what is now the United Workers Union, was terminated on the release of the results. Industry Super scrubbed it from its website.

The other industry funds that failed the performance test are run by the Australian Catholic Superannuation and Retirement Fund, Christian Super and the Victorian Independent Schools Super Fund.

Among the for-profit failures are funds run by Westpac (BT Super) and the Commonwealth Bank (Colonial First State).

The banking royal commission found that funds run by banks often pay money to other parts of the bank for services such as buying and selling bonds, rather than doing it themselves or through brokers who would get better prices.

In the dark, until now

Super customers needn’t know what happens. They don’t get bills.

Whereas electricity bills hurt when they are delivered and have to be paid, the bills for super fees (and hidden fees in the form of relentless underperformance) aren’t seen, and don’t have to be paid — the fees come out of the funds.

And the funds grow every year, even where they are squandered. Compulsory super throws in a fresh 10% of salary each year.

The aim of what’s happened this week is to make visible what is normally invisible, and to prod people into action.

An act of faith… in competition

The government could have gone down a different track.

Peter Costello, the long-serving Coalition Treasurer who now heads the Future Fund which manages government investments, wanted his successor to create a government super fund (run by his Future Fund) which it would default new workers into.

The Future Fund would have protected workers, but to do it, would have played safe. As it became dominant it would have stifled competition and the promise of better returns. Or that was the thinking.

Chester, O'Dwyer, Hume and Treasurer Josh Frydneberg decided instead to supercharge competition — to make crystal clear which are the funds to run from and the funds to run to. They are making running as easy as two clicks.

One in every 11 dollars we earn is funneled into superannuation. Legislated increases mean it will soon be one in nine.

It’s important it’s looked after.![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.