So you don’t believe the official inflation figures. Why would you? They show prices climbing at an annual rate of 1.1%

On Wednesday the update for June quarter is likely to show prices climbing at an annual rate three times as high — somewhere between 3% and 4%, which will probably be another reason you won’t believe them.

(As it happens, most of the “jump” will be because of a different starting point. The 1.1% figure reports what happened after the three months to March 2020. The update will report what’s happened since the three months to June 2020, when coronavirus restrictions triggered a plunge in petrol prices and a temporary childcare subsidy cut the price of most care to zero.)

Most of us don’t believe 1.1% or anything like it because it doesn’t accord with our experience. We see petrol prices climbing. We are presented with bills for electricity, gas and rates we find hard to pay.

But here’s the thing. As hard to believe as we find it, electricity, gas and petrol don’t cost us that much over the course of a year.

We notice petrol prices because they are displayed clearly on well-lit signs of a specified size, as is required by law. We notice electricity bills because they are large and usually arrive only four times each year.

And because we don’t like them. We pay less attention to spending we like.

Every few years the Bureau of Statistics surveys 10,000 households to determine what they spent over the course of a fortnight, and for less frequent expenses over the course of a year.

It uses what results to create a “basket” of representative goods and services, weighted according to actual expenditure.

Food accounts for the bulk of the basket — 17.3%. Alcohol accounts for another 5.3%. That’s right, 5.3%.

Compare the 5.3% of the basket we spend on alcohol to the 3.2% of it we spend on petrol, or the 3.8% on electricity and gas taken together.

Alcohol and food big ticket items

We spend almost as much on alcohol as on health, and more than on clothes.

If you reckon that’s not your household, fair enough. The basket represents the average household, as does the consumer price index (CPI) which measures the prices of the goods and services in the basket in the proportions they are in the basket.

And if your reckon you’d never admit to spending that much on alcohol, you’re also right. Alcohol and tobacco are two of the rare instances where the bureau nudges up what people report to take account of what’s actually sold.

Contrary to a widely-believed myth, the cost of housing is in the index, both in the form of rents and in the cost of building houses, rather than the cost of land (that’s regarded as an investment, as is the ownership of shares which are also not included in the index).

Most things included, though not illegal drugs

Some things aren’t the index but should be — superannuation management fees (the bureau is working on it) and recreational drugs and prostitution, which are excluded because it is “very difficult and indeed dangerous to obtain estimates of prices and expenditures, or to measure quality change”.

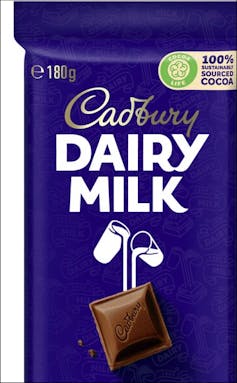

Quality matters. When Cadbury shrank its large blocks of chocolate from 250g to 200g a few years back and then to 180g, it wouldn’t have been right to merely record the price change.

The bureau adjusted up the recorded price to take account of the fact that people were getting less chocolate. But other changes are less straightforward. What do you do when VB reduces the strength of its beers (as it did) or the new model laptop has twice as much memory as the one it replaced?

For computers the bureau adjusts down the recorded prices of new models in line with a US formula.

For cars — which these days have features not previously dreamed of — it consults a panel of experts.

For other changes it lets improvements go through to the keeper, leaving recorded prices unadjusted even though the are getting better.

Beneath the hood, the CPI is changing

The bureau used to record prices using handheld devices in supermarkets and by ringing up suppliers and getting quotes. In the last few years it has moved to getting almost everything electronically — stores hand over data from checkout scanners, petrol stations report when prices have changed and upload sales data, and the bureau “scrapes” advertised prices from the web.

With those changes has come a revolution in what it is able to do. It used to collect prices in only a small number of representative outlets (which is why the index was limited to capital cities) and it used to record only the prices of “representative” items.

The stand-in for bread was the average price of a sliced white 650-750g loaf.

Better still, for the first time the bureau has information on how much is bought of each product at each price each quarter. This enables it make real-time adjustments to weightings in accordance with actual behaviour.

In 2011 when Cyclone Yasi destroyed banana crops in Queensland, the price of “fruit” recorded in the consumer price index surged to an unprecedented high. But the prices actually paid for fruit didn’t surge. Shoppers bought other fruits or canned fruit instead.

Next time that happens the CPI will scarcely move.

It’s making the index more of a cost of living index and less of a “cost of a fixed basket” index. It is happening for petrol too. The bureau is reporting the prices people actually pay, instead of the prices on offer.

None of this is to say that the CPI is perfect, but it would be wise to take the figure to be released on Wednesday seriously. It probably does a better job of recording changes in our cost of living than we’d do ourselves.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.