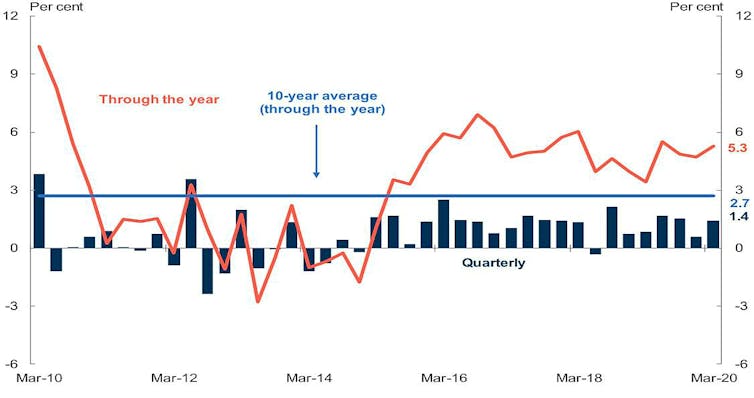

The picture of economic recovery painted by Prime Minister Scott Morrison is looking like a mirage. The 22 leading economists polled by The Conversation from 16 universities in seven states on average expect historically weak economic growth in all but one of the next five years, with growth dwindling over time.

In June, Morrison promised to lift economic growth by “more than one percentage point above trend” through to 2025.

Growth one percentage point above trend would average almost 4% per year.

Instead, The Conversation’s economic panel is forecasting annual growth averaging 2.4% over the next four years, much less than the long-term trend, tailing off over time.

The results imply living standards 5% lower than the prime minister expects by 2025.

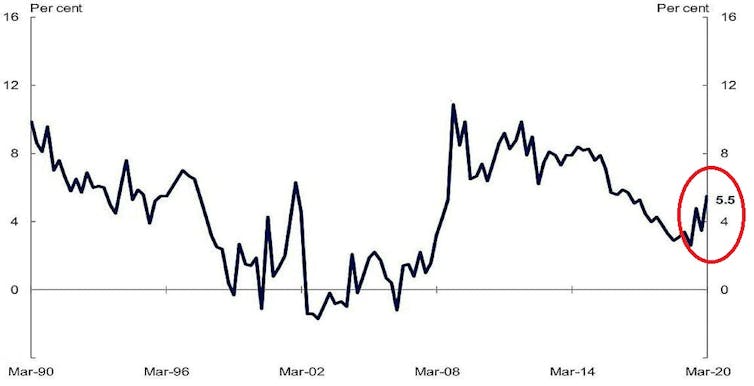

The panel expects unemployment to peak at around 10% and to still be above 7% by the end of 2021.

It expects wages to barely climb at all, by just 0.9% in 2020, the lowest increase on record and even less than the rate of inflation, which it expects to be only 1.2%. It expects the share market to sink further in the rest of this year before climbing a touch in 2021.

Non-mining business investment, on which much of Australia’s recovery depends, should bounce back only 3.3% in 2021 after slipping 9.5% in 2020.

Read more: The Reserve Bank thinks the recovery will look V-shaped. There are reasons to doubt it

The Conversation’s panel comprises macroeconomists, economic modellers, former Treasury, IMF, OECD, Reserve Bank and financial market economists, and a former member of the Reserve Bank board.

Several admitted to much greater uncertainty than usual. One pulled out, saying “it’s really a mug’s game right now”.

One, who did take part, despaired that forecasting had been reduced to “guessing, in the context of an unprecedented event”.

Several cautioned that climate change, along with the prospect of new waves of coronavirus, makes five-year forecasts especially difficult.

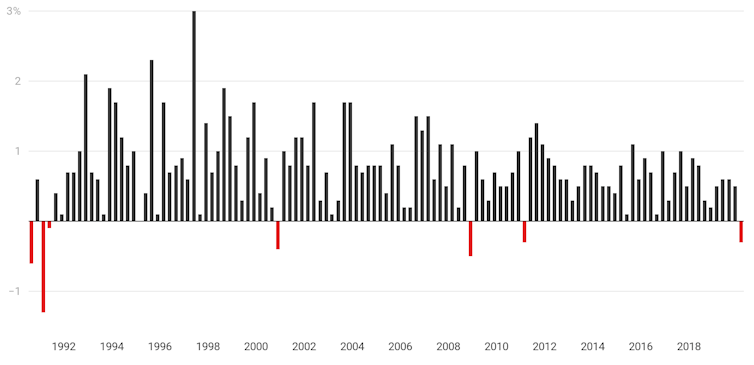

Economic growth

All of the panel expect incomes and production to shrink in the June quarter (the one finishing now) after shrinking in the March quarter, meaning we will be in a recession (if there was any doubt).

Some are expecting a small bounce in the September quarter, although they warn that if JobKeeper and the coronavirus JobSeeker Supplement end as planned when September finishes, economic activity will turn down again in the December quarter, creating what panellist (and former Labor politician) Craig Emerson describes as a “W-shaped economic trajectory”.

Panellist Julie Toth cautions there is “no magic V ahead”. Without government action on adaptation to climate change, productivity, industrial relations, inequality and other matters, the best that can be hoped for is a partial recovery of some of the growth that has been lost.

In in 2021 the panel expects the economy to recover only half of what it lost in 2020. After peaking at 2.9% in 2023, economic growth will slip back to less than it was before the crisis.

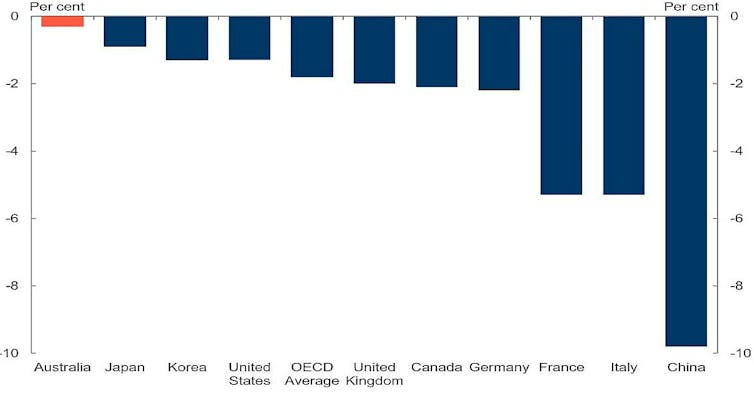

The panel expects China’s economy to shrink 2.3% this year before bouncing back 4% in 2021. It expects the US economy to shrink 5.6% before recovering only 2.2%.

Steve Keen suggests that the underlying US performance will be even worse. It will have attained its measured performance by being prepared to live with adverse health consequences.

Tony Makin notes that China’s near-term economic growth is likely to be hampered by a move towards deglobalisation in countries wanting to make their supply of goods and health equipment less reliant on China.

Unemployment

The forecasts for the peak in the unemployment rate range from the present 7.1% to 12%, with most of the panel expecting the peak before the end of the year.

Julie Toth points out that even with no further job losses, “which seems unlikely”, measured unemployment will continue to rise for some time as people who have stopped looking for work start looking again and return to being counted as unemployed.

Saul Eslake says this participation rate makes forecasting the unemployment rate a “crapshoot”. The rate will depend largely on how many people choose to define themselves as looking for or non longer looking for work.

Living standards

The panel expects household incomes and spending to fall by about 4% over the course of the year.

The best measure of living standards, real net national disposable income per capita, should fall 4.5%.

Real wages, a key component of living standards, are expected to fall.

Never in the 23-year history of the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ wage price index has annual wage growth been much below 2%. Until now the lowest annual growth rate has been 1.9%.

The panel is forecasting growth of just 0.9% throughout 2020, a mere half of the record low to date. The forecast calls into question the timing of the current legislated increases in compulsory superannuation contributions of 0.5% of salary per year for each of the next five years, scheduled to start next year and set to eat into wage growth.

Headline price inflation should be only 1.2%, and underlying (smoothed) inflation only 1%, but both would be more than wage growth, shrinking the buying power of wages.

Share market

The spectacular recovery in the Australian share market (up 29% since late March after sliding 36% since late February) is not expected to continue this year.

The panel expects the ASX 200 to end the year down 8% before climbing 2.3% in 2021.

But the forecasts for 2021 fan out over a wide range, from a fall of 10% to a rise of 10%.

Housing

Sydney and Melbourne house prices are expected to reverse their gains of 5% and 3% in the first half of the year to close about where they started (Sydney) and down 1.3% (Melbourne).

New home building is expected to plunge a further 10% in 2020 after sliding 10% in 2019.

On balance it is not expected to improve at all in 2021, although again the range of forecasts is wide, from a recovery of 10% (Renée Fry-McKibbin) to a further decline of 10% (Stephen Hail).

Business

Mining investment is expected to continue to recover in 2020 and 2021 after huge falls between 2014 and 2019 brought about by the collapse of the infrastructure boom and the completion of several large liquefied natural gas projects.

Non-mining business investment is expected to fall 9.5% throughout 2020 before inching back 3.3% in 2021.

The Australian dollar is forecast to end the year near its present 69 US cents.

After initially diving to a low of 59 US cents as the coronavirus crisis unfolded, it and other currencies climbed against the US dollar from late March as the US response to the crisis faltered.

The price of iron ore has climbed from late March to a high of US$103 per tonne, well above the US$55 assumed in last year’s budget papers.

The panel is expecting most of those gains to be kept, forecasting US$97 by the end of the year, enough to provide one of the few welcome pieces of news for framers of the October budget.

Again, the range of forecasts is wide, from US$64 a tonne (Stephen Anthony) to US$110 (Margaret McKenzie).

Government finances

After ending 2018-19 almost in balance, the budget deficit is expected to blow out to between A$130 billion and A$150 billion in 2019-20, weighed down by about the same amount of stimulus payments.

The forecasts for 2020-21 and 2021-22 are centred around $150 billion and $100 billion respectively.

It’s a hard outcome to pick, in part because it depends on both the needs of the economy and government decisions about how to respond to them. In a report issued on Monday the Grattan Institute called for the government to spend an extra $70 billion over two years.

Forecasts for the 2021-22 budget outcome range from a deficit of $200 billion (Rod Tyers) to a deficit of just $10 billion (Janine Dixon).

It’ll be easy to finance. The panel is forecasting a ten-year borrowing cost (bond rate) of just 1.4% per year, and it doesn’t expect it to climb that high until late 2021.

At the moment it’s 0.9%.

The Reserve Bank has committed itself to buy as many bonds as are needed to keep it low. The three major rating agencies have reaffirmed Australia’s AAA credit rating.

A survey of firsts

The 2020-21 survey is the first in 30 years not to ask for forecasts of the Reserve Bank cash rate, and the first since it has been published by The Conversation not to ask for the probability of a recession.

The Reserve Bank’s decision to push the cash rate as low as it conceivably could and leave it there for three years removed the need for the first. Australia’s descent into recession removed the need for the second.

The forecaster who proved to be the most farsighted on the recession was Steve Keen, who assigned a 75% probability to a recession in January at a time when Australia was dealing with bushfires and preparing to deal with coronavirus.

Other forecasters to assign a high probability to a recession (50%) were Julie Toth, Steven Hail, Warren Hogan and Richard Holden.

The Conversation 2020-21 Forecasting Panel

Click on economist to see full profile.

![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.