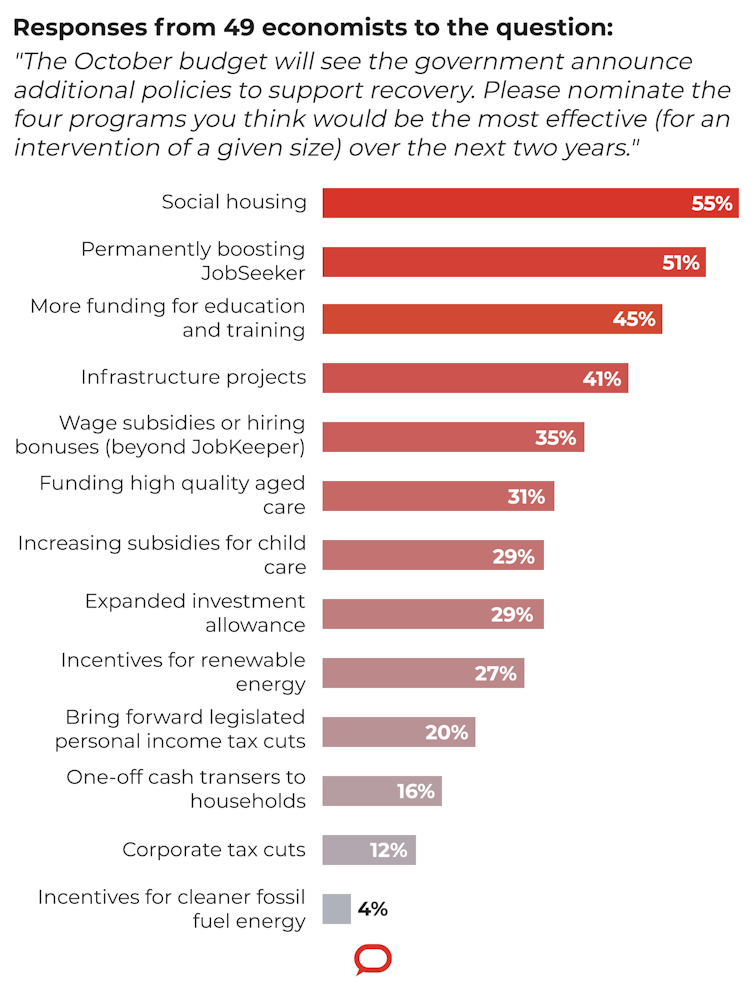

Overwhelmingly, Australia’s leading economists want the budget to boost social housing and the JobSeeker unemployment benefit rather than bring forward personal income tax cuts.

The 49 eminent economists who responded to Conversation-Economic Society of Australia pre-budget survey were asked to rate 13 options in terms of “bang for the buck” – effectiveness in boosting the economy over the next two years.

Among the options offered were boosting JobSeeker (previously called Newstart), wage subsidies beyond the expiry of JobKeeper, one-off cash payments to households, big infrastructure spending, bringing forward the personal income tax cuts, and company tax cuts.

The options were selected by a committee of the central council of the Economics Society and were presented to each surveyed economist in a random (shuffled) order.

The economists surveyed are Australia’s leaders in the fields of microeconomics, macroeconomics, economic modelling and public policy. Among them are former and current government advisers, former heads of statutory authorities, and a former member of the Reserve Bank board.

Each was asked to nominate the four most effective options for boosting the economy.

The most popular option, endorsed by 55% of those surveyed, was boosting spending on social housing.

Monash University econometrician Lisa Cameron said the budget provided an unusual opportunity to fix things for the long term while boosting the economy.

Social housing would leave us with something worthwhile (as did the school hall building program during the global financial crisis) in addition to providing work for the building industry. Alleviating homelessness would be a lasting benefit.

If it goes to the unemployed, it will be spent

The second most popular option, endorsed by 51%, was permanently boosting JobSeeker, previously known Newstart. The temporary boost in the A$282.85 per week payment was wound back last week and will end in December.

Melbourne University economist John Freebairn pointed out that with no real increase in Newstart since 1993 and many on it in demonstrable poverty, every extra cent spent on it will be spent rather than saved.

Supported by fewer than half of those surveyed, but third most popular at 45%, was more funding for education and training.

Flinders University labour market specialist Sue Richardson said education was labour-intensive, which would help with employment, and would assist young people severely hit by the pandemic to get the skills they would need to get jobs rather than stay unemployed.

Matthew Butlin, who heads the South Australian Productivity Commission, said the decimation of income from student fees means universities will have less money to subsidise research. There was a case for more direct funding of university research in the form of competitive grants for projects with practical applications.

The fourth most popular option was infrastructure spending, supported by 41%.

Why not a Hoover Dam, a new Opera House?

Many made the point that the projects chosen would have to be worthwhile in their own right, and feared this might not be the case. Others looked to big “nation building” projects along the lines of the Hoover Dam in the United States which was built during the Great Depression and employed 21,000 people.

“Why not building a massive dam in Australia? Why not building a new Sydney Symphony Orchestra building like the Berlin Philharmonie? Why not expand the National Parks? Why not building green libraries all over Australia?,” asked Sydney University’s Stefanie Schurer.

Read more: Homelessness and overcrowding expose us all to coronavirus. Here's what we can do to stop the spread

Done right, like the Sydney Harbour Bridge which was completed during the Great Depression, big imaginative projects could leave us with something valuable.

There was less enthusiasm for continued wage subsidies (35%) and an expanded investment allowance (29%) with University of NSW economist Gigi Foster saying investment allowances could be replaced with income-contingent loans along the lines of the Higher Education Contributions Scheme.

That way businesses could borrow to invest, with an obligation to repay if the investment paid off.

If it goes on tax cuts, it might not be spent

The same approach was taken by some to funding higher quality aged care (supported by 31%) and increasing subsidies for child care (29%).

Economic modeller Warwick McKibbin suggested funding child care through income-contingent loans (repayable on the basis of income) rather than subsidies.

Bringing forward the leglislated personal income tax cuts as proposed by the government and cash payments to households were relatively unpopular, supported by 20% and 16%.

Saul Eslake said that while he agreed with the treasurer that early tax cuts would “put money in people’s pockets”, there was no guarantee the high earners “into whose pockets most of that money would be put”, would take it out and spend it in sufficient quantity.

Read more: Frydenberg is setting his budget ambition dangerously low

Eslake suggested that rather than supporting households with cheques as happened during the financial crisis, households could be handed time-limited tradeable vouchers that could be spent in areas hurt by restrictions, such tourism and the arts, or used for other worthwhile purposes such as childcare or reskilling.

Among those who did support bringing forward the tax cuts was John Freebairn, who said that although presented as cuts, what was proposed would do little more than restore what had been lost to bracket creep, keeping income tax steady.

Company tax cuts an also-ran

Company tax cuts, once touted by former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull as the key to jobs and qrowth garnered minimal support, being backed by just six of the 49 economists surveyed.

The least popular option, backed by only two economists surveyed, was government support for cleaner fossil fuels such as natural gas, as the prime minister is promising. In contrast 13 (26%) backed support for renewable energy.

Individual responses

![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.