Overwhelmingly, Australia’s top economists would rather the budget funds measures to cut carbon emissions than cuts income tax or company tax.

They are also dead against rumoured cuts to petrol tax and the tax on beer.

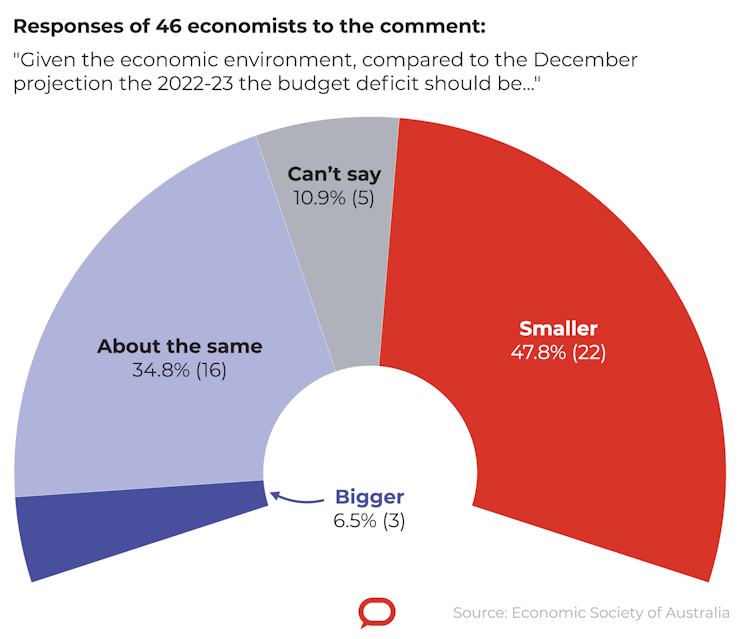

The Conversation’s pre-budget survey of a panel of 46 leading economists selected by the Economic Society of Australia finds almost half want a budget deficit smaller than the A$99.2 billion expected for 2021-22 and the $98.9 billion forecast for 2022-23 in the December budget update.

Higher commodity prices and lower than expected unemployment – which is lifting tax revenue while also cutting spending on benefits – is set to produce a deficit tens of billions of dollars lower, perhaps as low as $65 billion, absent new spending.

But a substantial chunk of those surveyed (41%) want an unchanged or bigger deficit to boost spending in other areas, including an accelerated transition to net-zero carbon emissions and Australia’s defence.

Arguing for a deficit about as big as last year’s, former OECD official Adrian Blundell-Wignall said while spending on defence was important, so too was spending on supply lines to make Australia less dependent on other countries. Events in the Ukraine showed supply chains were as important as weapons.

Curtin University’s Margaret Nowak said the huge reconstruction needs following the floods in NSW and Queensland suggested there was no potential to reduce the deficit and good reasons why it might climb.

Arguing with the majority in favour of a lower deficit, independent economist Nicki Hutley said the government should bank rather than spend any improved psoition to reduce debt ahead of higher interest rates. It would need “reserves at the ready” to deal with economic and geopolitical uncertainty.

James Morley of the University of Sydney said with the economy on the road to recovery, more government handouts would be likely to be inflationary, making it harder for the Reserve Bank to keep inflation within its target band.

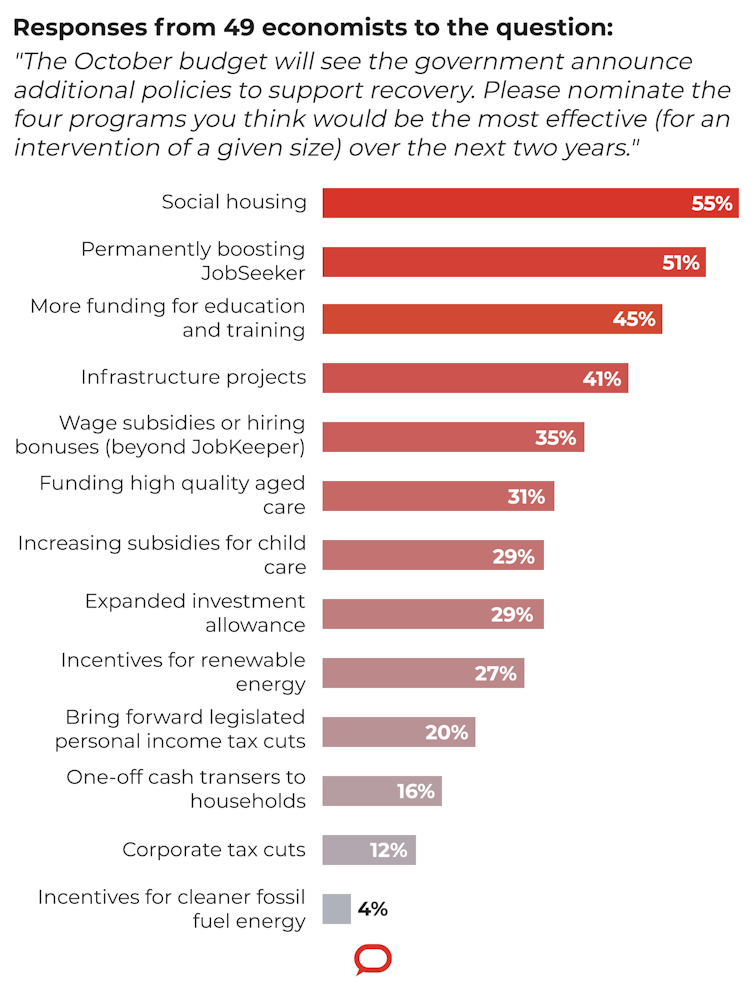

Asked to pick up to two spending or tax bonus measures from a list of twelve that would most deserve a place in the budget, more than 60% of those surveyed nominated spending on the transition to net zero carbon emissions.

University of Adelaide economist Sue Richardson said if she had the option, she would have picked “remove all subsidies to fossil fuels”. More than 90% of Australia’s energy now comes from fossil fuels. Reducing that – as the government has said it expects to do to get to net zero emissions by 2050 – will require a massive effort, “made much harder by starting so late”.

More than 32% of those surveyed backed increases subsidies for childcare, in part because it would allow more parents to do more paid work. More than 26% supported a temporary boost to JobSeeker and other payments; 13% supported increased defence spending; and 10.9% supported infrastructure spending and investment in domestic manufacturing.

Asked which of the measures should not be adopted, almost half (45%) picked a reduction in beer tax, and almost 35% nominated a reduction in fuel excise.

Saul Eslake said “gimmicks” such as cuts in beer or petrol excise failed to address the reality that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had serious economic consequences for Australia, including reducing national income. Governments can’t “pretend this hasn’t happened”.

Instead, what governments could do was ensure Australia’s lowest earners don’t bear the brunt of that economic pain.

The best ways to do this were temporary increases in social security payments, or a one-off special payment, and tax rebates for genuine low earners.

Eslake would fund them from the extra tax that will flow from the companies and shareholders who will benefit from the higher commodity prices following Russia’s invasion.

UNSW Sydney’s Nigel Stapledon was sceptical about higher social security payments. Given Australia’s experiencing a near five-decade low in unemployment, and unprecedentedly high number of job vacancies, he said it was hard to justify a higher rate of JobSeeker.

Also high on the list of measures panellists felt should not be adopted were further company tax cuts (21.7%) and bringing forward the Stage 3 tax cuts income tax cuts directed at high earners and due to start in July 2024 (21.9%).

The budget will be delivered on Tuesday night.

Individual responses:

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.