The good news is supposed to be that when the government gets out of the way “can-do capitalism” will have us roaring back to where we were before.

That’s the prime minister’s newest slogan, and we had better hope for more.

The unpleasant truth is that before the pandemic Australia’s economy was disturbingly and unusually weak. Can-do capitalism wasn’t doing what it should.

Reserve Bank chief economist Luci Ellis put it this way a few days after Morrison talked about freeing the engines of the economy to do their work.

In the decade or so leading up to the pandemic, there was a nagging sense that these engines of prosperity were running out of steam – investment was low, productivity growth was lagging, and many of the behaviours we associate with business dynamism were on the decline.

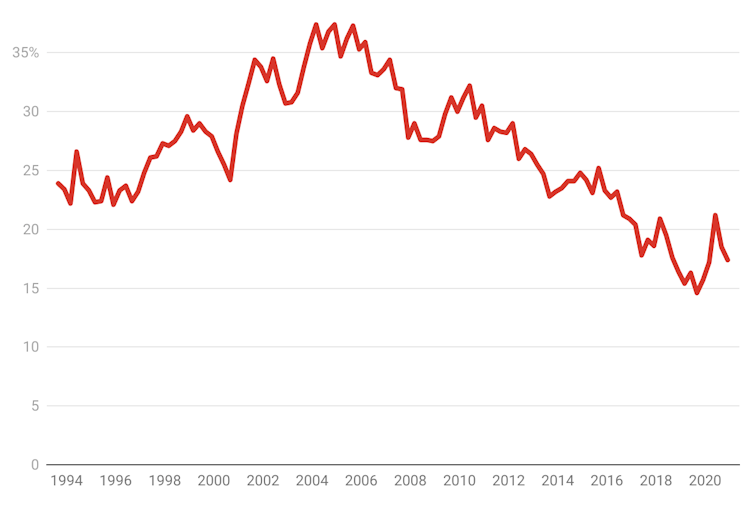

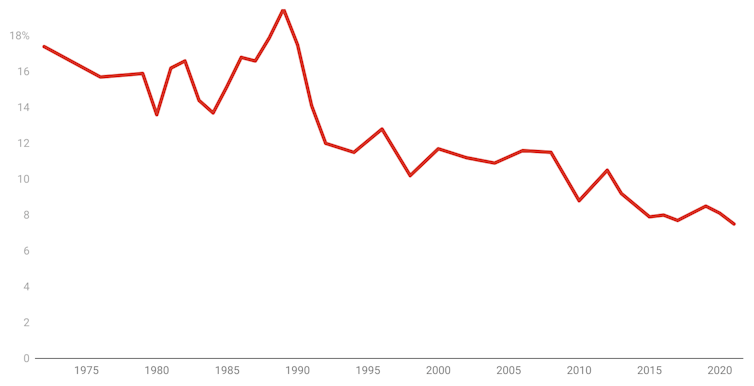

Outside of mining, business investment had been shrinking as a share of the economy for more than a decade.

Private non-mining business investment, share of nominal GDP

Outside of the ride-share industry, fewer businesses were being created and fewer businesses destroyed.

“For all the talk of disruption, the overall sense one gets from the data is of a bit less dynamism or inclination to shake things up,” Ellis said.

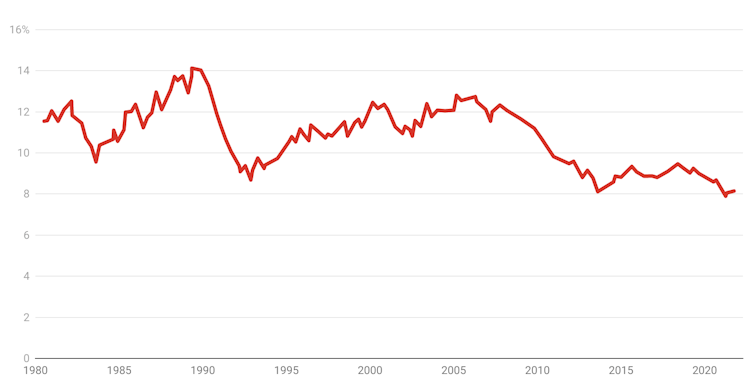

And we were in the middle of a “great resignation” of a different kind to the departures from jobs being seen in the United States.

Australians were increasingly resigned to staying in the jobs they had. Job switching had sunk to all-time lows.

Proportion of employed Australians who switched jobs during the year

In short, despite technological revolutions, despite a government saying it was getting out of the way, and despite record low interest rates that made it cheap to invest and expand, in the lead-up to COVID-19 businesses weren’t doing that. By the time the pandemic arrived, annual economic growth had slid to 2.1%.

Government hasn’t been holding business back

One thing Ellis says can’t explain the pre-pandemic reluctance of businesses to invest is government regulation pushing up costs. She says if costs had been rising, inflation wouldn’t have fallen to near record lows.

And if labour costs had been rising, wage growth wouldn’t have fallen to unprecedented lows, and firms would have been investing more in machines to replace workers.

Businesses themselves have been unusually cautious

There’s evidence to suggest that in the decade since the global financial crisis Australian (and other) firms have become more risk-averse.

Instead of falling with the falling cost of borrowing, the “hurdle” rates of return that businesses tell the Reserve Bank they require in order to justify investments have remained stubbornly high.

It’s a “won’t do” rather than a “can do” mindset, and Ellis says it might be because Australian managers don’t want to be associated with projects that fail, or because their firms have only limited management capacities and don’t want to commit to projects in case better ones come along.

Except for some firms

Her most intriguing suggestion is that some firms are market leaders at installing new technologies (especially those driven by artificial intelligence) – so much so that their competitors can’t catch up.

Tip Top Bakeries produces more than one million loaves of bread a day and delivers to more than 18,000 locations Australia-wide.

It used to send out its trucks in hub-and-spoke patterns using schedules drawn up by humans.

Since it began using artificial intelligence and machine learning to route trucks in configurations no human would have thought of, it has cut its distribution costs 14% and lifted its gross profit after distribution 7%.

Ellis makes the point that earlier technological innovations such as laptops and spreadsheets were easy to use.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning might be the first new technologies to be actually harder to use and require a rarer set of skills than those they replace.

The few “superstar” firms that adopt these new technologies (such as Woolworths with its fully automated distribution centre) are becoming able to do things their smaller competitors cannot, locking those lesser firms into a “low-wage, low-investment groove”.

Ellis cites evidence that the spread of technological knowledge has slowed, leading to a “winner-takes-all world” of increasing industry concentration.

It might still be possible to convince a lender you’ll be Australia’s next big thing in an industry with a market leader, but it’s getting harder.

‘Can-do capitalism’ needs help

The third possible explanation advanced by Ellis for the growth of the “think carefully before attempting” mindset over the past decade is in sharp contrast to Morrison’s distinction between “can-do capitalism” and “don’t-do governments”.

It’s to do with long-term cycles.

When conditions are weak, Ellis says, firms focus on defending what they’ve got instead of pursuing new opportunities.

We’ve been in that cycle for a decade, possibly made worse by governments withdrawing support in order to get nearer to balancing their budgets.

Now that governments are spending big and abandoning caution to fight the pandemic there’s a chance the cycle will turn.

It would be great if she turns out to be right.

If she is, it won’t be because the prime minister was right. It’ll be because business needed a leg-up.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.