It’s tempting to think home prices are soaring because there aren’t enough homes.

But that can’t explain the sudden takeoff from about the year 2000, the sudden takeoff from about 2013, and again now – against expectations – the stratospheric takeoff in the wake of the COVID recession.

Broadly, we’ve enough homes. The 2016 census found we had 12% more dwellings than households, up from 10% in 2001.

That’s 12% of our houses and apartments empty – used as holiday homes and second homes, or waiting for tenants.

If there really weren’t enough homes for people who wanted them, it would be more than property prices soaring; it would be rents.

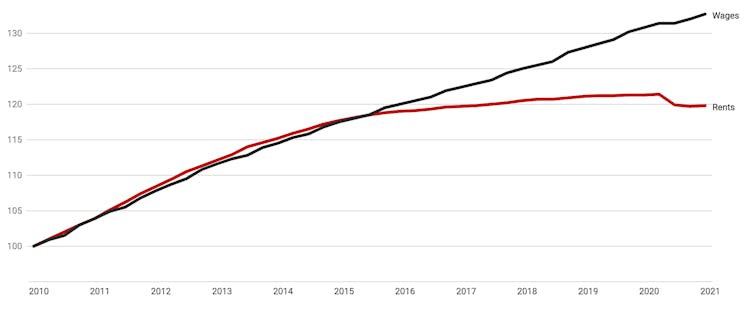

Instead, overall rents have been barely moving – growing even more slowly than wages – for half a decade.

Rent price index versus wage price index

For the half-decade from 2016, a half-decade in which Australia’s population grew by more than one million, Australian rents barely moved.

The supply of places to live in has kept pace with the demand for places to live in, but the supply of places to own has not.

More landlords, more tenants

If that sounds odd, remember people want to own houses for reasons other than living in.

Since about the year 2000, big numbers of Australians (and foreigners) have wanted to buy them to rent them out. They’ve wanted to become landlords.

Read more: Rents, not prices, are best to assess housing supply and demand

Twenty years ago only one in 15 of us were landlords. It’s now one in ten – more than two million of us.

To get those properties (other than where they’ve built them) they’ve had to outbid at auction the people who would have bought them to live in.

They’ve been helping create their own tenants, while pushing up prices.

We’re chipping away at Menzies’ legacy

From when Robert Menzies stepped down as prime minister in 1966 until the end of the 20th century, about 71% of Australian households owned the home they lived in – one of the highest rates in the world.

Since about 2000, owner-occupation has been sliding. The latest figures (themselves some years old) put it at 66%.

Among those aged 35 to 44, it has fallen to 63%

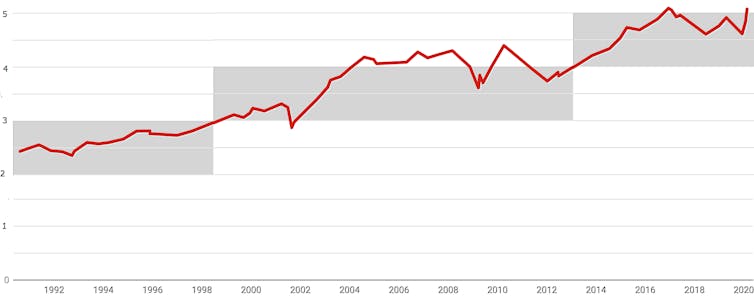

Over that time the cost of buying a home has shot up from two to three years’ household after-tax income to three to four years’ income.

Housing prices as proportion of household disposable income

What appeared to set things off was a decision by Prime Minister John Howard in 1999 to halve the headline rate of capital gains tax. Not that the committee he asked to investigate the idea recognised the possibility at the time.

The Ralph Review recommended that half, rather than all, of each capital gain be taxed, rather than the portion above inflation as had been the case since capital gains were first taxed.

The rationale was that this would “encourage a greater level of investment, particularly in innovative, high growth companies”.

A rush into property rather than high-tech companies

The review was right about the change encouraging investment, but wrong about the sort of investment.

Rather than buy shares in innovative companies, Australians bought rental properties like they never had before.

If they bid enough, they could borrow enough to negatively gear; to make sure their interest charges exceeded their income from rent, giving them annual losses they could offset against wages that would otherwise be taxed at high rates.

There was nothing new about negative gearing. It had been permitted from the beginning. What was new was the opportunity to later sell the property at a profit, knowing only half of the profit would be taxed.

Investors could offset all of their losses and be taxed only half their eventual gain.

Pretty soon, more than a third of the money lent for housing each month went to landlords. For several dizzying months during 2015 it was 45%. First home buyers struggled to compete.

In 2016 then treasurer Scott Morrison raised the prospect of winding things back, saying negative gearing had led to “excesses”.

APRA cleared up what our leaders could not

Labor went to two elections promising to do just that and the Coalition came out in support of the practice in public.

Behind the scenes, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority was using its power over lenders to force lending to landlords down, getting it down ahead of COVID to 27% of new housing loans.

APRA succeeded in taking the pressure off prices where politicians couldn’t.

But that’s far from the whole story. There are other more deep-seated reasons why house prices are climbing, and they too have little to do with demand for accommodation.

Read more: Zoning isn’t to blame for Australia’s soaring house prices

Prices took off again from about 2014, shifting up from three to four years’ household income to between four and five years. That time it was Australians getting richer after years of mining booms and being able to borrow more cheaply.

Houses in general mightn’t be a good investment (there being a regularly increasing supply) but houses in prime positions were in fixed supply, there being only so many good locations.

And then it fed on itself. The father of modern economics John Maynard Keynes described investing as a game in which the best strategy is not to put money into what you think is worthwhile, but to put money into what you think other people will think is worthwhile.

It’s happening again

He spoke of a third degree, where “we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be”, and added there might be fourth, fifth and higher degrees.

It’s happening again. With mortgage rates at new extreme lows and wealthier Australians having come out of the crisis with their wealth intact, it makes sense to do what others are doing and push up prices to buy before others push them up further.

It’s nothing to do with a shortage of housing, but for many it will push home prices further out of reach. That’s because in Australia housing is two things: accommodation and a form of speculation.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.