The last week of campaigns used to be frantic, behind the scenes. In public, right up until the final week, the leaders would make all sorts of promises, many of them expensive, with nary a mention of the spending cuts or tax increases that would be needed to pay for them.

Then, in a ritual as Australian as the stump jump plough, days before the vote the leaders’ treasury spokesman would quietly release pages and pages of costings detailing “savings”, which (astoundingly) almost exactly covered what they were spending, meaning they could declare their promises “fully funded”.

It was a trap for oppositions. Whereas governments seeking reelection could have their savings costed by the enormously-well-resourced departments of treasury and finance before campaigns began, oppositions were forced to rely on little-known accounting firms with little background in government budgeting.

The errors, usually not discovered until after people voted, were humiliating.

Costings time was danger time

In 2010, a treasury analysis of the opposition costings prepared by the Coalition’s treasury spokesman Joe Hockey and finance spokesman Andrew Robb found errors including double counting, booking the gains from a privatisation without booking the dividends that would be lost, and purporting to save money by changing a budget convention.

The Gillard government evened the playing field in 2011 by setting up an independent Parliamentary Budget Office to provide oppositions with the same sort of high-quality advice governments got, helping ensure they didn’t make mistakes, and enabling them to publish the advice in the event of disputes.

Ahead of the 2019 election the PBO processed 3,000 requests, most them confidential.

This means you should take with a grain of salt Treasurer Josh Frydneberg’s assertion that Labor has “not put forward one policy for independent costing by treasury or finance” – these days opposition costings are done by the PBO.

But the PBO didn’t end the costings ritual. In fact, it institutionalised it.

The ritual derives from the days when, on taking office, new governments proclaimed themselves alarmed, even shocked, at the size of the deficits they inherited. From Fraser to Hawke to Howard, they used the state of the books they had just seen to justify ditching promises they had just made.

The Charter of Budget Honesty improved things

Howard applied a sort-of science to it, memorably dividing promises into “core” and, by implication, “non-core” in deciding which to ditch.

Then that game stopped. Since 1998, Howard’s Charter of Budget Honesty has required the treasury and department of finance to publicly reveal the state of the books before each election, making “surprise” impractical.

But the legislation that set up the Parliamentary Budget Office entrenched the costings ritual by requiring each major party to hand it a list of its publicly announced policies by 5pm on election eve, in order for the PBO to publish an enduring account of their projected impact on the budget.

Which is why the parties have remained keen to get in early and find savings.

Sometimes, savings backfire

In 2016 this led to a human and financial tragedy. Three days before the election Treasurer Scott Morrison announced what came to be called “Robodebt” as part of a savings package designed to to offset spending. It was to save $2 billion.

Five years later in the Federal Court, Justice Bernard Murphy approved the payment of $1.7 billion to 443,000 people he said had been wrongly branded “welfare cheats”, ending what he called a “shameful chapter” in Australia’s history.

The costings document the Coalition released on Tuesday is less dramatic.

It says it will offset $2.3 billion in new spending over four years with a $2.7 billion boost in the efficiency dividend it imposes on departments to restrain spending.

Labor abandons the game

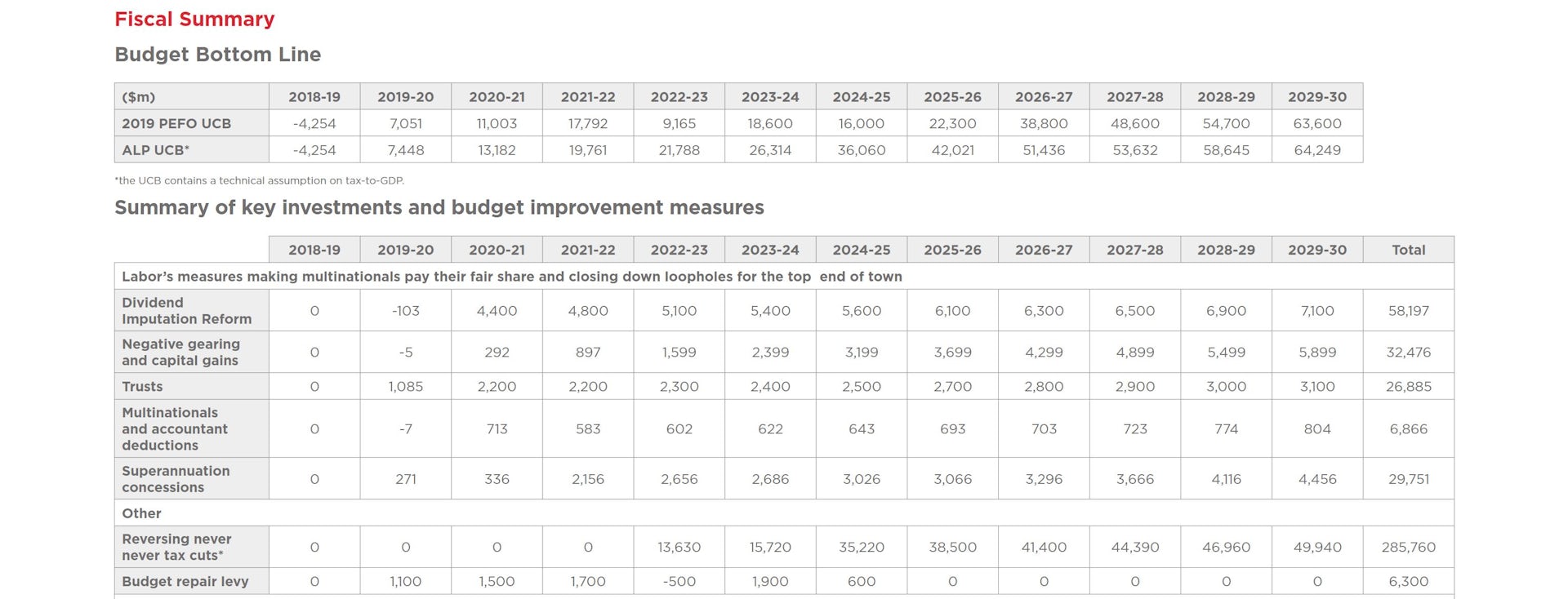

Labor will release its costings on Thursday, and here’s what’s changed. It says it won’t offset its spending.

Shadow Treasurer Jim Chalmers wants to be judged not on the size of spending, but on what the spending is for.

The most important thing here is not whether deficits are a couple of billion dollars each year better or worse than what the government is proposing. What matters most is the quality of the investments.

He points to the hundreds of millions borrowed to support the economy during the pandemic, the $20 billion he says was spent on companies that didn’t need it, and the $5.5 billion spent on French submarines that now won’t be built.

In sporting parlance, Chalmers has walked away from the field.![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.