Imagine you were trying to design a system that would hold back wages. You would design one pretty much like the one we’ve got today.

That’s why the government wants to change it.

Those of us on enterprise bargaining agreements get our wage rises locked in only every three or so years. If we didn’t lock in enough in last year’s agreement to cover this year’s sudden outbreak of inflation, there’s nothing much we can do about it for another two or so years.

It’s a built-in inertia identified by financial services firm JP Morgan in its attempts to explain to foreign clients why Australian wages growth is so low.

Australian enterprise agreements, JP Morgan explains in a note to clients, both delay wages growth and trim its peaks.

Here’s how that came about – and how the Albanese government’s new industrial relations law might finally end Australians’ pay freeze.

Wages used to be mostly set by awards

For nearly a century, Australian wages were generally set by judges in state and federal industrial relations tribunals. They had the power to intervene and set an “award” wage for an industry or occupation in which there was a dispute. And it was easy enough for unions and employers to create disputes.

Because they almost always intervened, the tribunals got to ensure that wages didn’t move too much relative to each other, and it got an insight into the state of the economy from the government, which made submissions.

From one point of view, the strength of this peculiarly Australian system of setting wages was that each employer covered by a decision was compelled to deliver the same increase as its competitors, meaning none were disadvantaged.

From another point of view, this strength was becoming a weakness. The weak firms as well as the strong had to pay the increases, whether it was easy or not.

Enterprise agreements unleashed productivity

In the early 1990s, perhaps with an eye to the possibility that an incoming Coalition government might make even greater changes, the Keating Labor government changed the law to channel the workers and employers within each workplace into enterprise bargaining.

The tribunals would have a more limited role, checking that each enterprise agreement passed a “better off overall” test, and continuing to set awards that became more like backstops, slipping below what most workers (usually through their unions) were able to negotiate with individual employers.

Workers and unions did well at first, because they were able to get together with employers and nut out ways to save money to pay for wage rises – something they had had little incentive to do when wages were set centrally.

And it was something that could only really be done at the level of each enterprise, because each was different, and it was the workers on the ground who knew how to make it better.

Zombie agreements and frozen wages

But productivity couldn’t be unleashed in the same way forever. After a while, the easy gains had been had. Workers got good pay rises in return for streamlining unwieldy processes at the start, then had few unwieldy processes left to streamline.

Productivity surged during the first decade, until the early 2000s. Then employers became more cautious about granting pay rises, and by the 2010s became good at stringing out negotiations or letting agreements expire, which meant they rolled over as “zombie agreements” without an increase.

As the Business Council explained in a report on the state of enterprise bargaining in 2019, agreements that had lapsed but were still operational came to act “like a wage freeze for some employees”.

With union membership down from 40% of workers when enterprise bargaining began, to just 14% in 2020, there was little workers on frozen agreements could do to get more, other than fall back on awards, which at least usually climbed with inflation.

It means the system has come to work in a way hardly anyone actually intended. It is acting as a brake on pay rises, while becoming more centralised.

The Reserve Bank says it can see some signs that wages growth is picking up, even in new enterprise agreements, but that it will take some time to flow through to all agreements in general because of the “multi-year duration” of the agreements.

How the new law could break the pay freeze

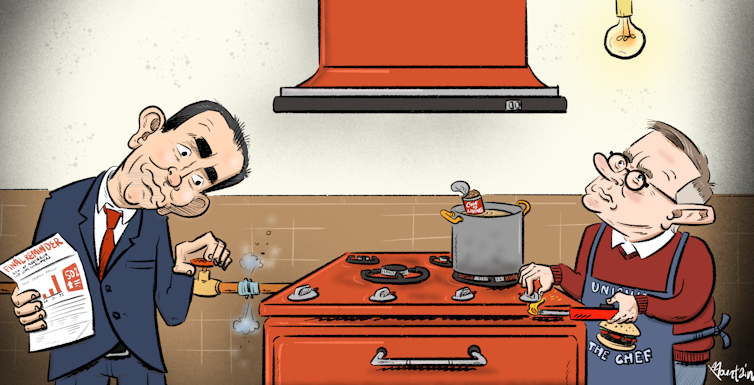

What the Albanese government has proposed – and is about to finally get through the Senate with the help of the Greens and independent David Pocock – is an attempt to bust the inertia.

Expanding multi-employer bargaining will allow employers to bargain knowing their competitors will have to pay what they pay.

Air-conditioning manufacturers have already begun talks with the Australian Manufacturing Workers Union in a bid to drive up workplace standards and pay in a way they know won’t be undercut by cheaper competitors.

Allowing employers with genuine ongoing enterprise agreements to escape multi-employer bargaining will encourage more genuine agreements.

And loosening the “better off overall” test will make it easier to get agreements of all kinds registered.

Particularly helpful will be “supported bargaining”, in which the Fair Work Commission will sit around the table with workers in fields such as childcare, who have traditionally found it hard to bargain. Where necessary, the commission will pull in outside funders (such as the government for childcare) for talks.

None of it will work miracles. But it should help. And it’s unlikely to hurt.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.