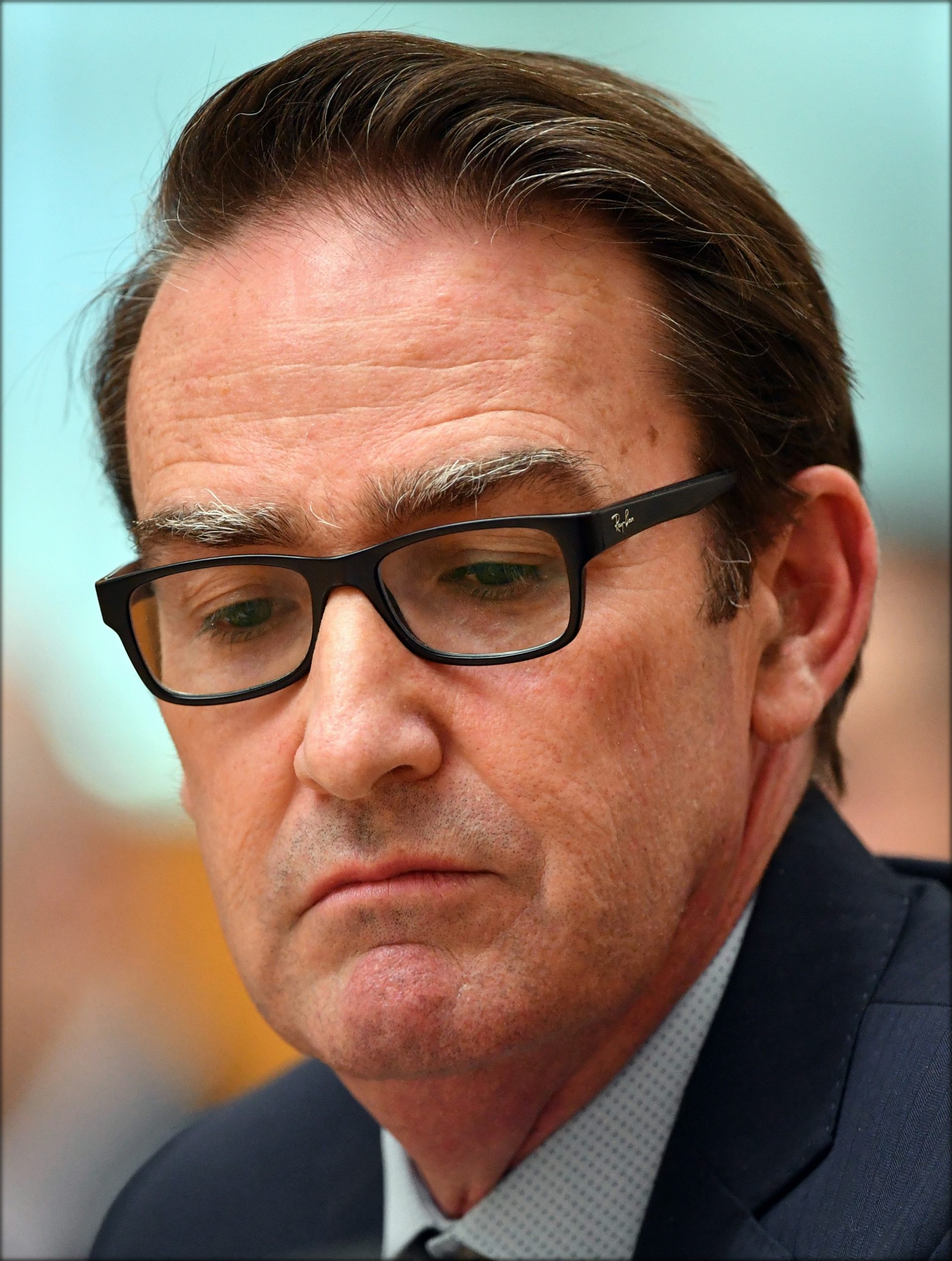

Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy – in the job for for just weeks after moving across from the department of infrastructure last month – has dismissed talk of spending big on infrastructure in order to escape an economic downturn.

Such calls “sound straightforward, but in practice are difficult to achieve”, he told a Senate hearing on Wednesday.

The timing requirements of fiscal stimulus are hard to give effect to while ensuring large projects are well planned and executed, and cost and capacity pressures are managed. There are some opportunities though, usually related to smaller projects and maintenance expenditure. The Commonwealth and state Governments are currently actively exploring these opportunities.

More broadly he made it plain that it was the role of the Reserve Bank rather than the Treasury to provide economic stimulus.

The bank has already cut its cash rate to a record low of 0.75% and has indicated it is prepared to consider unconventional monetary policy measures that would have the effect of cutting a wider range of rates.

However, bank Governor Philip Lowe said last week such tools would be most effective “when used together with a broader set of policies”, including government spending and tax policies.

Without crisis, no need to spend more

Kennedy rejected the idea of extra spending except in an emergency, saying Treasury could best serve Australia’s interests by a “stable and predictable” policy framework that kept the budget near balance over time.

There would be times when a downturn cut revenue and increased spending on support payments, pushing the budget into deficit, but beyond allowing those so-called automatic stabilisers to operate there wasn’t normally a case for doing more.

The exceptions were “periods of crisis”.

“It is important to consider separately broader policy objectives and temporary responses to crisis,” Kennedy said.

“The circumstances or crisis that would warrant temporary fiscal responses are uncommon.”

Although Australia’s economy is not in crisis, Brexit, the US-China trade war and turmoil in Hong Kong have slowed economic and trade growth worldwide, as businesses opt to stay on the sidelines.

No crisis, but weak growth worldwide

In Australia, economic growth had been unusually weak, weighed down by weak household spending which was itself the result of weak income growth, weak house prices, weak housing investment, and weaker than expected non-mining investment.

Mining investment was down sharply, as was to be expected after the completion of several large liquefied natural gas projects.

Given low interest rates, it was “somewhat of a puzzle” that business investment was not growing faster. Partly that might be because the “hurdle rates” businesses use to assess projects have not been adjusted down as they should have been. Partly it might be because of uncertainties surrounding the global economy and technological change.

Structural factors may also be at play — it is not clear what business investment looks like in a world where more than two thirds of our economy is now services based.

The budget tax cuts that flowed into returns from July have not yet led to a “particularly large improvement” in household spending.

Wages, investment “somewhat of a puzzle”

“We will continue to assess the data on consumption as it becomes available, but it is worth noting that even if households initially use the tax cuts to pay down debt faster, this will still bring forward the point at which households could increase their spending,” Dr Kennedy said.

It is possible that spending might have been even weaker without the tax cuts.

Holding back the economy during the year to June has been drought and dry weather which knocked 0.2 percentage points of the economic growth. Holding it up has been larger than normal growth in government spending that contributed 0.2 percentage points more to economic growth than was normal.

Read more: Why we've the weakest economy since the global financial crisis, with few clear ways out

No one had been able come up with a complete explanation for Australia’s unexpectedly low rate of wage growth. One explanation might be that even though the unemployment rate of 5.2% was unusually low, increases in employment were drawing in older workers and women rather than pushing up wages.

Ultimately what was needed to sustain higher wage growth was productivity growth, and that would be difficult to achieve while business investment was weak. The Productivity Commission had come up with a set of recommendations state and federal ministers were working their way through.

Although economic growth has been very low - just 1.4% in the year to June – it grew more strongly in the last half of that year than the first. It might be “strengthening from here”.![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.