What’s the difference between Google and Facebook?

One difference is that last week Google agreed to pay Australian news outlets for their content in the face of a threat of government action to force it to.

Facebook did not, temporarily removing Australian news sources from its feeds, a decision it only reversed after winning a range of concessions.

Another is the reason why.

It’s that Google faces competition, whereas Facebook really doesn’t.

In economists’ language, that’s because Facebook enjoys a rare “network effect”, Google scarcely at all.

If I want to switch from Google to another search engine (something I’ve done) it costs me next to nothing. I might find it hard to move my search history over (although there’s probably an app for that) but otherwise the new search engine will either be better, worse or about the same as the one I left. I’m free to find out.

Google faces competition

It means that Google is forced to defend itself from competition (or the threat of competition) by providing an extraordinarily good service.

Not so Facebook. Although a relatively new concept in economics, the idea of a network effect dates back to at least 1908 when the president of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, Theodore Vail, spelled it out in a letter to stockholders.

“A telephone, without a connection at the other end of the line, is not even a toy or a scientific instrument,” he wrote. “It is one of the most useless things in the world. Its value depends on the connection with the other telephone — and increases with the number of connections.”

Facebook faces hardly any

The idea has since been expressed in a mathematical formula, but there’s no need to get into details. The world’s first telephone was indeed useless, the second allowed one household to reach only one other. But by the time there were millions, and almost every household had one, each telephone became incredibly valuable, allowing that household to reach almost every other household.

A startup that tried to compete with the phone system would be offering a very unappealing product. It wouldn’t be able to offer anything like the connections of the existing system until a huge proportion of the population signed up, meaning people would be reluctant to sign up, meaning it would stay unappealing.

Read more: We allowed Facebook to grow big by worrying about the wrong thing

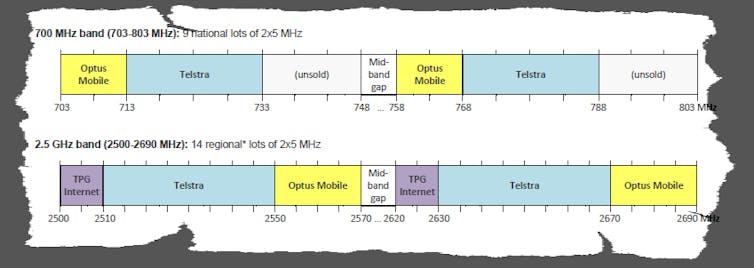

Which is the point Vail was making. When it gets big enough, the telephone service is something close to a natural monopoly. There’s no point in anyone setting up a competing one (and in Australia we haven’t — the competing companies, Telstra, Optus and so on, share the one network).

The ASX stock exchange is another example, as is eBay. You could try to sell something on a different platform, but you wouldn’t reach nearly as many potential customers, so you mightn’t get as good a price.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission puts it this way in its report on Facebook: even if the government made it easier for a user to switch to another network, perhaps by mandating the transfer of data,

if none of the user’s friends or family are moving away from Facebook, that user would be unlikely to switch platforms

The “lock in” that happens when a network gets so big people feel they have to use it means it doesn’t have to treat them particularly well to get them to stay.

Seventeen million Australians use Facebook every four weeks — a huge proportion of the population, and an even bigger proportion of the population aged over 14 (80%).

Without Facebook, it would be hard to know what family and friends and long-lost classmates are up to — whether or not Facebook offers news. It doesn’t need to treat its users particularly well to get them to stay.

Facebook isn’t quite like the phone system. Young people find the fact that so many old people can use it to check up on them a turn-off and go elsewhere. But for the Australians already on it (that’s most Australians) it’s worth staying.

And there’s room for smaller specialised networks.

Linkedin has its own network for people concerned about the jobs market. If that’s the world you’re in, it’s wise to be on it because of the huge number of other such people who are on it. There’s not much point leaving it for something else.

Winner take all

It wasn’t always that way for Facebook. Fifteen years ago MySpace was how people connected, but not that many of them — it hadn’t grown to the point where network effects took over. When they did, there could be only one clear winner, and it happened to be Facebook.

Now not even its bad behaviour (Roy Morgan finds it is Australia’s least-trusted brand) can stop most people using it.

In the same way as people who want the lights on generally have to use the electricity company, people who want to catch trains generally have to use the railway and people who want to drive cars generally have to buy petrol, people who want to stay in touch generally have to use Facebook.

Which makes the government’s decision to remove its vaccination advertising campaign from Facebook silly. Facebook reaches 80% of its target audience.

Facebook has become a (trans-national) utility, unconcerned about its image. Attempts by one government, or even a coalition of governments, to force it to do anything are pretty much a lost cause.

No-one wanted it to be like this, and it’s not like this for Google. Facebook has moved beyond our control.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.