Does it feel like you’re being charged more for all sorts of things these days, from groceries to banking? Turns out, you’re right.

While we might be more likely to remember prices that go up than prices that go down, the very best evidence – assembled by Australia’s Treasury, the federal government’s lead economic adviser – says your suspicions are right. We really are being charged more than we used to be two decades ago.

Coupled with the latest profit reports from Australia’s biggest supermarkets and banks, including Tuesday’s half-year results from Coles, it suggests we are contributing more to company profits than we used to.

Climbing price markups

The Treasury estimates show in the 13 years between 2003-04 and 2016-17, the average price markup – the difference between the cost of a product and its selling price – across all Australian industries climbed 6%.

That’s extra profit, taken from your wallet, going to the people selling you things.

Those Treasury estimates are contained in a background paper prepared for the competition inquiry being undertaken by a panel including Productivity Commission chair Danielle Wood, former Competition and Consumer Commission chief Rod Sims, and business leader David Gonski.

At the same time, the average share of each industry held by its biggest four firms edged up from 41% to 43%.

Profit margins are also higher here than in more competitive markets overseas.

This is true in banking, where the big four have taken over St George, BankWest, and the Bank of Melbourne – and are about to take over Suncorp.

It’s also true in supermarkets, where the big two, Woolworths and Coles, have taken over or seen off Franklins, Bi-Lo and Safeway.

Bigger profit margins than overseas

Coles supermarkets reported earnings before adjustments of A$1.73 billion on sales of $19.778 billion in the half year to December – a profit margin of 8.7%.

Last week, Woolworths supermarkets reported earnings of $2.45 billion on sales of $25.648 billion – a margin of 9.6%.

By way of comparison, the dominant UK supermarket group, Sainsbury’s, has a profit margin of 6.13%.

In banking, the Commonwealth Bank has just reported a return on equity (profit as a proportion of shareholders’ funds) of 13.8%. National Australia Bank reported 12.9%.

While on a par with the big banks overseas, those recent returns are a good deal higher than CommBank’s 11.5% and NAB’s 10.7% reported two years ago.

Little hope for groceries

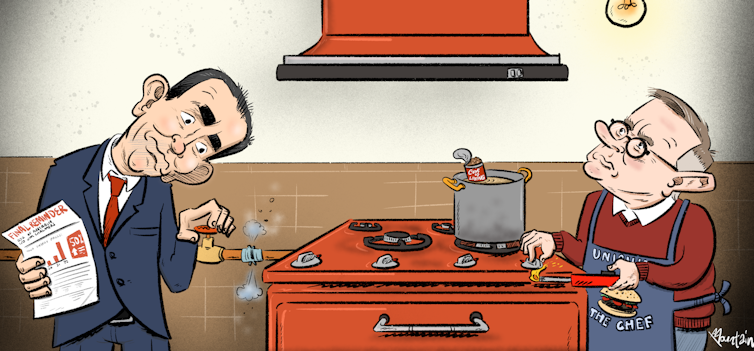

For supermarkets, there’s not a lot the government can do, apart from launching an inquiry, and perhaps giving Australian authorities the power to break up firms that abuse their market power.

But Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has said he isn’t keen on giving Australian authorities the sort of powers available to authorities in the United States and the United Kingdom, saying (incongruously) Australia is “not the old Soviet Union”.

And doing anything short of that would be unlikely to have much effect. Australia’s two supermarket giants have invested a fortune in high-tech warehouses and distribution systems, which new rivals would be hard-pressed to match.

Hope for more competitive banking

But for banks it’s altogether different. Richard Denniss of the Australia Institute has come up with the idea, and it’s a beauty.

It’s for the government to provide a low-cost banking service – expanding on services it already offers.

The costs would be so low, other banks might decide to add features and resell them in the same way as resellers sell mobile phone and NBN services.

The primary function of any bank is to provide a numbered account into which Australians can deposit and withdraw funds.

The Australian Tax Office does this already, at an incredibly low cost.

The tax office gives every working Australian a tax file number. Employers deposit money into these accounts, and – should the tax office owe a refund – taxpayers withdraw them.

Some taxpayers ensure their tax is overpaid, so they withdraw later.

Denniss describes it as a bank account with the world’s clumsiest interface.

The government could offer bank loans

It wouldn’t be much of a stretch from improving that interface to offering government loans.

In fact, government loans are already provided in some circumstances: such as to retirees with home equity through the home equity access scheme, and to Centrelink recipients through advance payments.

It woudn’t be much more of stretch to provide loans more broadly, at an incredibly low administrative cost. The government already lends against the value of homes.

Back in the days when the federal government owned the Commonwealth Bank, it had to cover the high costs of running bricks and mortar branches.

Freed from those costs, the government could now offer a low-cost, technology-enabled basic banking service that would tempt us away from the big four banks – unless they offered better value.

Of course it would cost money, although a lot of it has already been spent setting up the system of tax file numbers and accounts. And of course the banks would hate the idea. That would be the point.

But doing what we can to stop Australians being overcharged is important, not only for wage earners but also for businesses.

The competition inquiry the government has launched is a good start. It shouldn’t be frightened about where it might lead.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.