Despite appearances – especially in the United States – the era of high inflation isn’t set for a comeback in the view of Australia’s leading economists, and most see no need for the Reserve Bank to lift interest rates next year.

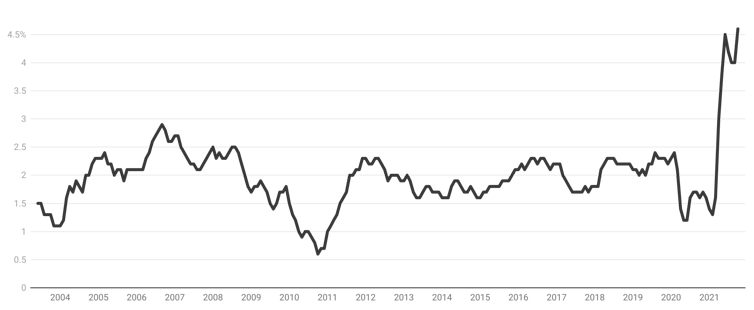

In the US, figures released last week showed the consumer price index surged 6.2% in the year to October, the most since 1990. So-called “core” inflation (which excludes volatile prices) climbed 4.6%, also the most for 30 years.

US underlying inflation

Former US treasury secretary Larry Summers is talking about a jump to 11% as over-heating becomes entrenched, necessitating rate hikes in the United States, Britain and Australia.

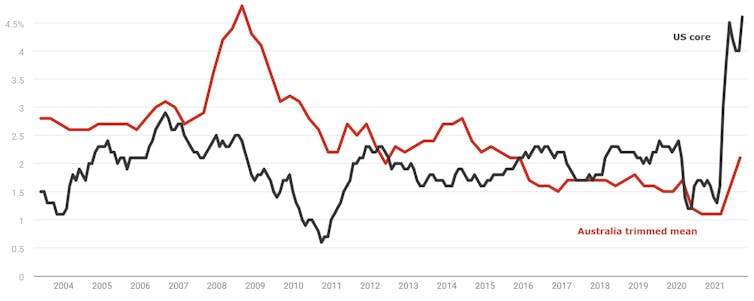

But the 55 leading Australian economists surveyed by the Economic Society of Australia and The Conversation this week aren’t buying it. They point out that Australia’s underlying inflation rate (while climbing) is much lower, at 2.1%.

US and Australian underlying inflation

Whereas in the US wages climbed 4.6% in the year to September, in Australia they climbed 1.7% in the year to June, an official figure that will be updated with readings from the September quarter on Wednesday.

32 of the 55 top economists surveyed by the Economic Society of Australia rejected the proposition that the current combination of Australian fiscal and monetary policy posed “a serious risk of prolonged above-target inflation”.

Only 12 supported it. When weighted by the confidence of respondents expressed on a scale of 1-10, backing for the proposition shrank from 22% to 20%.

Independent economists Nicki Hutley and Saul Eslake said fiscal policy (government spending) was set to tighten as COVID spending programs expired, making projected high inflation unlikely.

Harry Bloch said the prices of Australian services were predominantly determined here, by Australian wage rates, which were held back by the bargaining strength of unions and government wage setting policies.

Big inflation would require wage inflation

Matthew Butlin, until this year South Australia’s Productivity Commissioner, said prices were rising quickly in asset markets such as those for land and shares.

“The pressure simply to recover the real value of wages, let alone increase their real value, will be significant,” he said. Australia risked a wage-price spiral.

Rana Roy foresaw temporary high inflation until high energy prices and supply chain disruptions passed, but “temporary” in the sense that the hyperinflation in Germany’s Weimar Republic was temporary, lasting from 1921 to 1923.

Suppressing the higher inflation would require deliberate corrective action.

Higher rates, but not yet

Asked when the Reserve Bank would next lift its cash rate to combat inflation, most nominated 2023. Only 15 of the 52 economists who answered the question expected a hike next year, putting the majority at odds with financial market pricing which backs in several hikes during 2022.

Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe said earlier this month he didn’t expect to have to lift the cash rate until 2024, a proposition backed by only 10 of the 52 economists who tackled the question.

Most (33 of the 55) believed the Reserve Bank had managed the economy well during the past five years, effectively used the tools available to it to achieve its goals of maintaining the stability of the currency, ensuring full employment and furthering the “economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia”.

Only 15 believed the bank had managed things badly.

Fabrizio Carmignani said it could be argued the bank had kept its cash rate too low for too long and also argued that it had failed to get inflation up to its target band, two apparently contradictory positions.

Paul Frijters said that by targeting the underlying inflation rate as calculated by the Bureau of Statistics, which excludes much of housing, the bank had “cooked the books” to avoid having to increase interest rates.

John Quiggin said the bank should abandon its inflation target of 2-3% and instead target nominal GDP growth, doing whatever was needed to get the economy to grow at a nominal rate of 6-7%.

No clear case for an inquiry

The economists surveyed were divided about the need for an independent review of the Reserve Bank after next year’s election.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the International Monetary Fund have backed a review of the kind proposed by Labor, which would examine the bank’s mandate, board structure, and hiring and communication processes.

Asked about the idea in the survey, former Labor minister Craig Emerson said the bank had consistently undershot the 2% lower bound of its inflation target, causing unnecessarily high unemployment and low wages growth in part because it had targeted projected rather than actual inflation, and its projections had fallen short.

In October last year Governor Philip Lowe announced the bank would switch to targeting actual inflation, saying it would not be lifting its cash rate “until actual inflation is sustainably within the target range”.

Other panellists including Joaquin Vespignani argued that by targeting only measured inflation the bank had created “a bubble in the housing market which is not consistent with economic prosperity”.

More economists on the RBA board

Panellists including Ken Clements argued there was a case for appointing more board members with the economic expertise needed to challenge bank officials.

Former OECD official Adrian Blundell-Wignall argued the bank’s structure and goals were the broadly right ones. We should “not try to fix what isn’t broken”.

James Morley was concerned an independent commission of inquiry might be “highly politicised and lead to unrealistic expectations about what monetary policy can and should do”.

The Bank of Canada reviewed its performance and frameworks in cooperation with the federal government every five years, a practice that would work well in Australia.

Detailed responses:

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.