Australia’s top economists are reluctant to endorse the use of either cash incentives or lotteries to boost vaccination rates.

A survey of 60 leading Australian economists selected by the Economic Society has instead overwhelmingly endorsed a national advertising campaign (90%), vaccine passports for entry to high-risk settings such as flights, restaurants and major events (85%) and mandatory vaccination for high-risk occupations (81.7%).

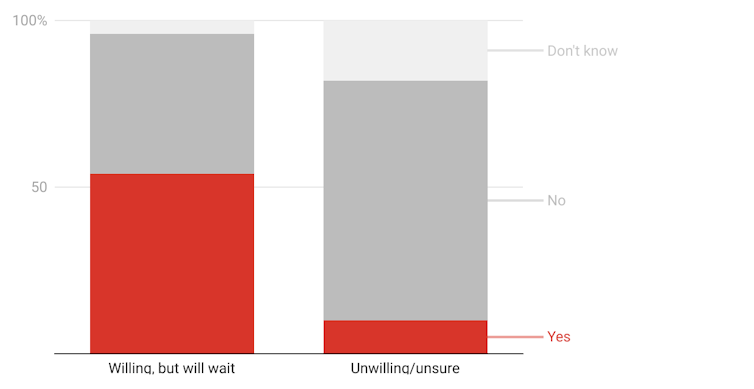

Offered six options for boosting uptake once supply was in place and asked to pick as many as they liked, only 35% picked cash incentives and only 31.7% lotteries.

Many said advertising and vaccine passports should work on their own.

Others, such as Uwe Dulleck from the Queensland University of Technology, suggested that while cash and lotteries might also work, “maybe a little bit”, they were ethically no better than coercion.

The panel selected by the Economic Society includes leading experts in the fields of behavioural economics, welfare economics and economic modelling. Among them are a former and current member of the Reserve Bank board.

Read more: Paying Australians $300 to get vaccinated would be value for money

Michael Knox of Morgans Financial said the most important thing for getting Australians vaccinated was “trust”.

Trust could be built through a national advertising campaign delivered via doctors and chemists as well as the media.

Others supported advertising in principle, but doubted the government’s ability to do it well.

The Australian government’s A$3.8 million “tacos and milkshake” campaign about sexual consent did not inspire confidence, said RMIT’s Leonora Risse.

The University of Sydney’s Stefanie Schurer said an easy and effective measure would be to simply reduce “transaction costs”. Many vaccinations don’t take place simply because they are difficult to arrange.

‘What’s in it for me?’

Former OECD director Adrian Blundell-Wignall said as a child in the 1950s, if you turned up on the day the polio or smallpox caravan was at school, you were either lined up and injected with a vaccine, or else given a lump of sugar with vaccine on it to swallow. “There was no debate, thank heaven.”

Underlying the reticence of two-thirds of those surveyed to endorse vaccine payments — along the lines of the $300 suggested by Labor or “VaxLotto” suggested by the Grattan Institute — was a concern that it would change the debate to “what’s in it for me?”.

Reserve Bank board member Ian Harper said “what’s in it for the rest of us” was at least as important.

Read more: Why lotteries, doughnuts and beer aren't the right vaccination 'nudges'

Macquarie University’s Elisabetta Magnani said cash incentives could “validate mistrust”. The University of Sydney’s Susan Thorp was concerned they might set a precedent.

“Would people expect another cash incentive in future for COVID vaccination boosters or for flu shots or childhood diseases?” she asked.

‘My body, my choice’

Two of the 60 economists surveyed backed “no additional measures”. UNSW Sydney economist Gigi Foster said the choice should be an individual’s, made without social shaming, goading, moralising or outright coercion.

But others strongly disagreed about individual choice. The University of Melbourne’s Leslie Martin said while personal choice mattered, it “should not come at a cost to others”. And Stefanie Schurer said in a world where individual freedoms were already wildly curbed, vaccination mandates and passports did not seem off the charts:

A requirement for children to meet immunisation schedules has been attached to childcare payments since 1998 and for the Family Tax Benefit A supplement from 2012. Families can access their family-related Centrelink payments only if their child’s vaccination schedule is up-to-date. In 2015 exemption rules were tightened to make it harder for so-called conscientious objectors. States such as NSW have also introduced vaccination mandates for children to access childcare centres.

Several of the economists who supported cash payments and lotteries said they should be held in reserve and used only as a “last resort”.

The Grattan Institute’s Danielle Wood said even if they only shifted the dial a few percentage points, there was a big difference between getting 75% of people vaccinated and 80%.

Eighty per cent might be enough to get a re-opening of the economy to “stick” without the need for further lockdowns.

Detailed responses: