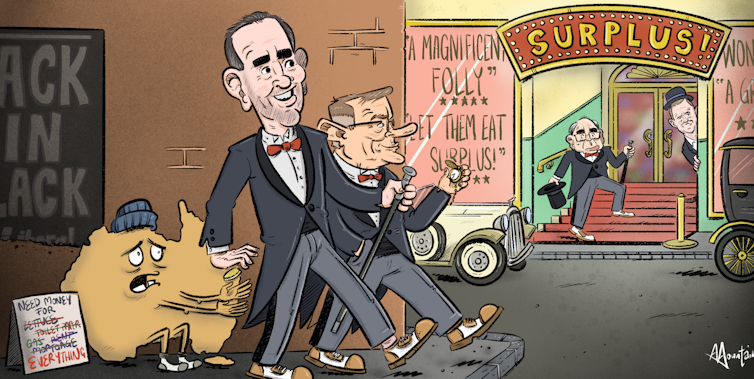

Like Kevin Rudd before him, Anthony Albanese is taking an odd approach to evidence.

Before becoming prime minister in 2007, Rudd promised to deliver “good evidence-based policy in terms of producing the best outcomes”.

Yet while in office, Rudd made several of his most important and far-reaching decisions without bothering to compare outcomes to cost – that is to say, without a formal cost-benefit analysis. Those decisions included lifting compulsory super contributions and his preferred model of the national broadband network.

In the case of the national broadband network, Rudd explicitly rejected pleas for a cost-benefit analysis, a stance his finance minister justified by saying

we just formed the view that in effect we had to make the clear decision that said this is the outcome we are going to achieve, come hell or high water, because it is of fundamental importance to the future of the Australian economy.

In opposition, Albanese led the way in pushing for evidence-based policy. So far, his government is reverting to type – even shutting down a move to improve accountability on big projects last week. But there is also one small sign of progress, thanks to a new institution you probably haven’t heard about yet.

Albanese just blocked what he once championed

Back when he was Rudd’s infrastructure minister, Albanese set up Infrastructure Australia, a statutory authority.

At the time, Albanese declared: “This government is determined to bring a fresh approach to developing and modernising the nation’s physical infrastructure — replacing neglect, buck-passing and pork-barrelling with long-term planning”.

Returning to opposition as Labor’s infrastructure spokesman in 2014, Albanese tried to strengthen Infrastructure Australia’s independence.

He moved in parliament to require the authority to perform a cost-benefit analysis of all proposed projects costing $100 million or more, “regardless of what the political views are around a particular project”.

The government blocked the motion. There the idea languished – until last week.

Last Wednesday, independent MP Allegra Spender moved almost exactly the same motion – in almost exactly the same words – requiring Infrastructure Australia to perform a cost-benefit analysis of all proposed projects costing $100 million.

Labor and the Coalition combined to vote the motion down.

There’s something about the idea of making decisions that don’t make financial sense that becomes irresistible to politicians once they are actually in office.

Already this year, Albanese has pledged $240 million to Tasmania for a stadium and $2.2 billion to Victoria for the suburban rail loop.

Spender also unsuccessfully tried to require Infrastructure Australia to publish its infrastructure audits and collate data on costs after projects were completed.

It “astonished” her there was no established mechanism by which governments could learn from what had happened with past projects.

A (small) win for evidence

Yet amid the dismay, there’s a sliver of hope. In the same week the government voted down attempts to give Infrastructure Australia more teeth, it formally unveiled its new Australian Centre for Evaluation.

The pet project of Labor’s assistant minister for treasury, former economics professor Andrew Leigh, it will be tasked with examining whether government programs work, and doing it before they are rolled out.

The method will be randomised trials, something Leigh knows a lot about having written a book about them while in opposition, called Randomistas.

Leigh says what he is proposing isn’t an audit; that happens after the event. And it isn’t a cost-benefit study; that’s done before the event, but on a spreadsheet without real-world knowledge of what will happen.

It will mean implementing programs or pilots in ways that let the government compare the results with what would have happened without them.

Too many programs are rolled out everywhere, all at once, without an opportunity to find out what would have happened if the program wasn’t there.

Inspiration from Mexico

Leigh’s favourite example comes from Mexico. In 1997, the government there was considering changing the way it delivered food and energy subsidies to poor households. It wanted to try handing out cash instead, but on the proviso that children of the families receiving it attended school and health clinics.

Rather than changing the system for all 500 villages at once, it changed it for half in May 1998 and the other half in December 1999. The 18-month window where one half did one thing, and the other half did the other, let it see which half prospered the most.

It was the half that switched to conditional cash handouts – but Mexico wouldn’t have been sure without that trial.

$2 million per year for control groups

Leigh wants to build in that sort of randomisation here. “You might already have a program which is going to be rolled out over the course of two years,” he says. “Why not randomise the way in which you roll it out, so year two is the control group for year one?”

The treasury has been given an extra $2 million per year to get the centre started. Leigh says it will hire about a dozen people and act as a consultant to other departments that are planning programs.

It’s a small start, and at this stage a small exception to what seems to be the prevailing view among governments that they already know what’s best.

Just imagine how much good the new centre could do if it’s allowed to – including, to quote Albanese, finally replacing “neglect, buck-passing and pork-barrelling with long-term planning”.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.