Booking a place to stay on holidays has become a reflex action.

The first thing many of us do is open a site such as Wotif, Hotels.com or trivago (all of which are these days owned by the US firm Expedia), or their only big competitor, Booking.com from the Netherlands.

Checking what rooms are available – anywhere – is wonderfully easy, as is booking, at what usually seems to be the lowest available price.

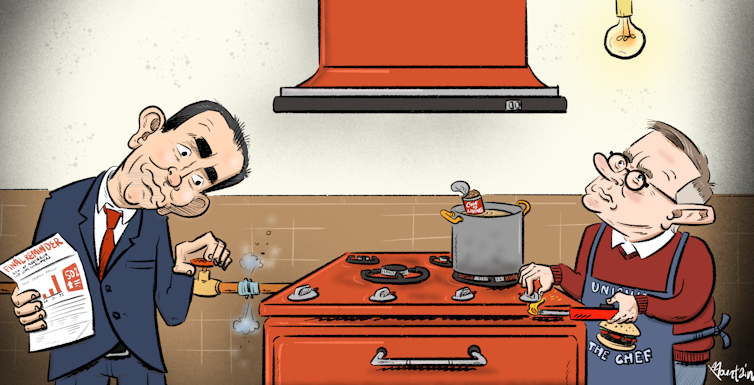

But Australia’s Assistant Competition Minister Andrew Leigh is concerned there might be a reason the price seems to be the lowest available. It might be an agreement not to compete, or the fear of reprisals against hotel owners who offer better prices.

Agreements to not compete

Leigh has asked the treasury to investigate, and if that’s what it finds, it may be the booking sites have the perverse effect of keeping prices high, especially when the substantial fees they charge hotels are taken into account.

For now, the treasury is seeking information. It has set a deadline of January 6 for hotel operators and booking sites to tell it:

the typical fees charged by online booking platforms

the details of any agreements not to compete on price

whether hotels that try to compete get ranked lower on booking sites.

What’s likely to come out of it is a ban on so-called price-parity clauses that prevent discounting, or a ban on “algorithmic punishment,” whereby hotels that do discount get pushed way down the rankings on the sites.

But in the meantime, there are things we can do to get better prices, and they’ll help more broadly, as I’ll explain.

Flight Centre precedent

Back in 2018, in a case that went all the way to the High Court, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) forced Flight Centre to pay a penalty of A$12.5 million for attempting to induce airlines not to undercut it on ticket prices.

That the ACCC eventually won the case might be an indication price-parity clauses are already illegal under Australian law. But it’s a difficult law to enforce. This is why the treasury is considering special legislation of the kind in force in France, Austria, Italy and Belgium.

The ACCC has known for some time that Expedia and Booking.com have included clauses in their contracts preventing hotels offering the same room for any less than they do, even directly.

Rather than take the big two to court, in 2016 the ACCC “reached agreement” with them to delete the clauses that prevented hotels offering better deals face-to-face.

The concession that conceded little

From then on, hotels were able to offer better deals than the sites over the phone or in person, but not on their own websites. Given we are less and less likely to walk in off the street or even use the phone to book a hotel, it wasn’t much of a concession.

Then, in 2019, with the Commission under renewed pressure from hotel owners for another investigation, Expedia (but not Booking.com) reportedly waived the rest of the clauses, giving hotel owners the apparent freedom to advertise cheaper prices wherever they liked including on their own sites without fear of retribution.

Except several appear to fear retribution, and very few seem to have jumped at the opportunity.

Algorithmic punishment

An Expedia spokesman gave an indication of what might be in store when he was quoted as saying a hotel that undercut Expedia might “find itself ranked below its competitors, just as it would if it had worse reviews or fewer high-quality pictures of its property”.

Being ranked at the bottom of a site is much the same as not being ranked at all, something Leigh refers to as “algorithmic punishment”.

It’s not at all clear the present law prevents it, which is why Leigh is open to the idea of legislating against it.

Although you and I may not often think about what hotels are paying to be booked through sites such as Wotif and Booking.com, and although what’s charged to the hotel isn’t publicised, it appeard to be a large chunk of the cost of providing the room.

One figure quoted is 20%. Leigh says hotel owners have told him the fees are in the “double digits”, something he says is quite a lot when you consider the sites don’t need to clean the toilets, change the sheets or help on the front desk.

‘Chokepoint capitalism’

What this seems to mean (the treasury will find out) is almost all bookings are more expensive than they need to be because firms that sit at the “chokepoint” between buyers and sellers are squeezing sellers.

A hotel could always abandon the sites and offer much cheaper prices, but for a while – perhaps forever – it will be much harder to find.

In their defence, the operators of the platforms might say they need to get the best offers from hotels in order to make it worthwhile for the operators to invest in their sites, an argument the treasury is inviting them to put.

In the meantime, with some hotels reluctant to put their best rates on their websites, but with them perfectly able to offer better rates over the phone, there’s a fairly simple way we can all get a better deal – and help fix the broader problem by weight of numbers.

If we look up the best deal wherever we want online, and then phone and ask for a better one (or a better room), we might well find we get it. We might be saving the owner a lot of money.

Leigh reckons the more we do ring up, the more the sites might feel pressure to discount their own fees, helping bring prices down even before he starts to think about writing legislation.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.